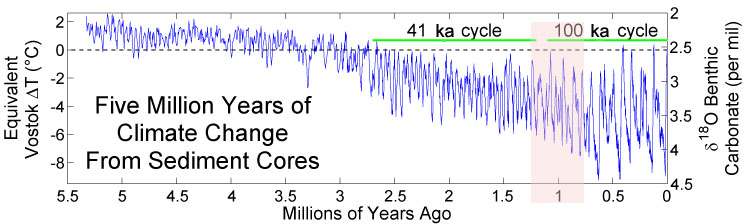

In 1976 three scientists from Columbia and Brown (USA) and Cambridge (UK) Universities published a paper that revolutionised the study of ancient climates (Hays J.D., Imbrie J. and Shackleton N.J. 1976. Variations in the Earth’s Orbit: Pacemaker of the Ice Ages. Science, v. 194, p. 1121-1132; DOI: 10.1126/science.194.4270.1121). Using variations in oxygen isotopes from foraminifera through two cores of sediments beneath the floor of the southern Indian Ocean they verified Milutin Milankovich’s hypothesis of astronomical controls over Earth’s climate. This centred on changes in Earth’s orbital parameters induced by gravitational effects from the motions of other planets: its orbit’s eccentricity, and the tilt and precession of its rotational axis. Analysis of the frequency of isotopic variations in the resulting time series yielded Milankovich’s predictions of ~100, 41 and 21 ka periodicities respectively. The time spanned by the cores was that of the last 500 ka of the Pleistocene and thus the last 5 glacial-interglacial cycles. Subsequently, the same astronomical climate forcing has been detected for various climate-induced changes in the earlier sedimentary record, including the glacial cycles of the Carboniferous and Neoproterozoic, Jurassic climate changes due to oceanic methane emissions and many other types of cyclicity during the Phanerozoic.

As well as time series based on isotopic and other geochemical changes in marine cores, other variables such as thickness of turbidite beds or cyclical repetitions of short rock sequences such as the ‘cyclothems’ of Carboniferous age (repetitions of a limestone, sandstone, soil, coal sequence) have also been subject to frequency analysis. Sedimentary features that have not been tried are gaps or hiatuses in stratigraphic sequences where strata are missing from a deep-sea sequence. These signify erosion of sediment due to vigorous bottom currents in sequences otherwise dominated by continuous deposition under low-energy conditions. Three geoscientists from the University of Sydney, Australia and the Sorbonne University, France, have subjected records of gaps in Cenozoic sedimentation from 293 deep-sea drill cores to time-series analysis to discover what such ‘big data’ might reveal as regards climate fluctuations on the order of millions of years (Dutkiewicz, A., Boulila, S. & Müller, R.D. 2024. Deep-sea hiatus record reveals orbital pacing by 2.4 Myr eccentricity grand cycles. Nature Communications, v. 15, article 1998; DOI: 10.1038/s41467-024-46171-5).

In theory gravitational interrelationships between all the orbiting planets should have an effect on the orbital parameters of each other, and thus the amount of received solar radiation and changes in global climate. As well as the Milankovich effect, longer astronomical ‘grand cycles’ may therefore have been reflected somehow in Earth’s climatic history (Laskar, J. et al. 2004. A long-term numerical solution for the insolation quantities of the Earth. Astronomy & Astrophysics, v. 428, p. 261-285; DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361:20041335). Based on Laskar et al.’s calculations Adriana Dutkiewicz and colleagues sought evidence for two predicted ‘grand cycles’ that result from orbital interactions between Earth and Mars. These are a 2.4 Ma period in the eccentricity of Earth’s orbit and one of 1.2 Ma in the tilt of its axis.

The authors were able to detect cyclicity in the hiatus time series that is close to the 2.4 Ma Mars-induced waxing and waning of solar heating. Warming would increase mixing of ocean water through cyclones and hurricanes. That would then induce more energetic deep ocean currents and more erosion on the deep ocean floor: more gaps in sedimentation. Cooler conditions would ‘calm’ deep ocean currents so that deposition would outweigh evidence of erosion. The 1.2 Ma axial tilt cyclicity is not apparent in the data. Interestingly, the ~2.4 Ma cyclicity underwent a significant deviation at the Palaeocene-Eocene Boundary’ (56Ma), seemingly predicted by Laskar et al’s astronomical solutions as a chaotic orbital transition between 56 and 53 Ma. Dutkiewicz et al. also chart the relations between the sedimentary-hiatus time series and major tectonic, oceanographic, and climatic changes during the Cenozoic Era, and found that terrestrial processes did disrupt the Mars-related orbital eccentricity cycles.

The findings suggest that long-term astronomical climate forcing needs to be borne in mind for better understanding the future response of the ocean to global warming. Also, if Mars had such an influence so must have Venus, which is more massive and closer. That remains to be investigated, and also the effects of the giant planets. In the very distant past there behaviour may have resulted in unimaginable astronomical changes. According to the bizarrely named Nice Model a back and forth shuffling of the Giant Planets was probably responsible for the Late Heavy Bombardment 4.1 to 3.8 billion years (Ga) ago. Such errant behaviour may even have triggered the flinging of some of the Sun’s original planetary complement out of the solar system and changed the outward order of the existing eight. Fortunately, the present planetary set-up seems to be stable …

See also: Dutkiewicz, A., & Müller, R. D. 2022. Deep-sea hiatuses track the vigor of Cenozoic ocean bottom currents. Geology, v. 50, p. 710–715; DOI: 10.1130/G49810.1; Mars drives deep-ocean circulation in Earth’s oceans, study suggests. Sci News, 13 March 2024.