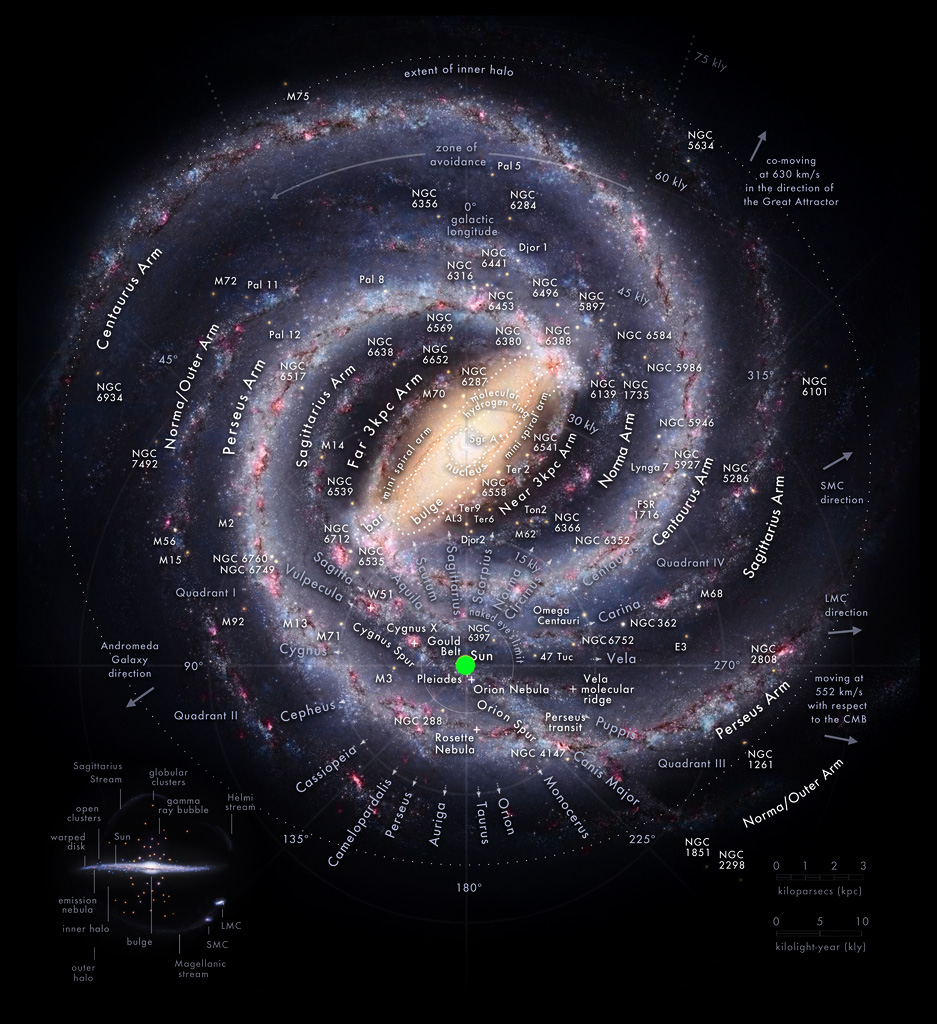

Michael Rampino and Ken Caldeira of New York University and the Carnegie Institute have for at least three decades been at the forefront of studies into mass extinctions and their possible causes, including flood-basalt volcanism, extraterrestrial impacts and climate change. As early as 1993 the duo reported an ubiquitous 26-million year cycle in plate tectonic and volcanic activity. In Rampino’s 2017 book Cataclysms: A New Geology for the Twenty-First Century the notion of a process similar to Milutin Milankovich’s prediction of Earth’s orbital characteristics underpinning climate cyclicity figured in his thinking (see Shock and Er … wait a minute, Earth-logs, October 2017). Rampino postulated then that this longer-term geological cyclicity could be linked to gravitational changes during the Solar System’s progress around the Milky Way galaxy. He was by no means the first to turn to galactic forces, Johann Steiner having made a similar suggestion in 1966. The notion stems from the Solar System’s wobbling path as it orbits the centre of the Milky Way galaxy about every 250 Ma, which may result in its passage through a vast layered variation in several physical properties aligned at right angles to galactic orbital motions. This grand astronomical theory is ‘a story that will run and run’; and it has. It is possible that the galaxy has corralled dark matter in a disc within the galactic plane, which Rampino and Caldeira latched onto that notion a year after it appeared in Physical Review Letters in 2014.

As I commented in my brief review of Rampino’s book: “As for Rampino’s galactic hypothesis, the statistics are decidedly dodgy, but chasing down more forensics is definitely on the cards.” Indeed they have been chased in a recent review by the pair and their colleague Sedelia Rodriguez (Rampino, M.R., Caldeira, K. & Rodriguez, S. 2023. Cycles of ∼32.5 My and ∼26.2 My in correlated episodes of continental flood basalts (CFBs), hyper-thermal climate pulses, anoxic oceans, and mass extinctions over the last 260 My: Connections between geological and astronomical cycles. Earth-Science Reviews, v. 246 ; DOI: 10.1016/j.earscirev.2023.104548; reprint available on request from Rampino). They base their amplified case on much more than radiometric dates of continental flood basalt (CFB) events matched against the stratigraphic record of biotic diversity. Among the proxies are published measurements of mercury and osmium isotope anomalies in oceanic sediments that are best explained by sudden increases in basaltic magma eruption; signs of deep ocean anoxia; new dating of marine and non-marine extinctions in the fossil record, and episodes of sudden extreme climatic heating.

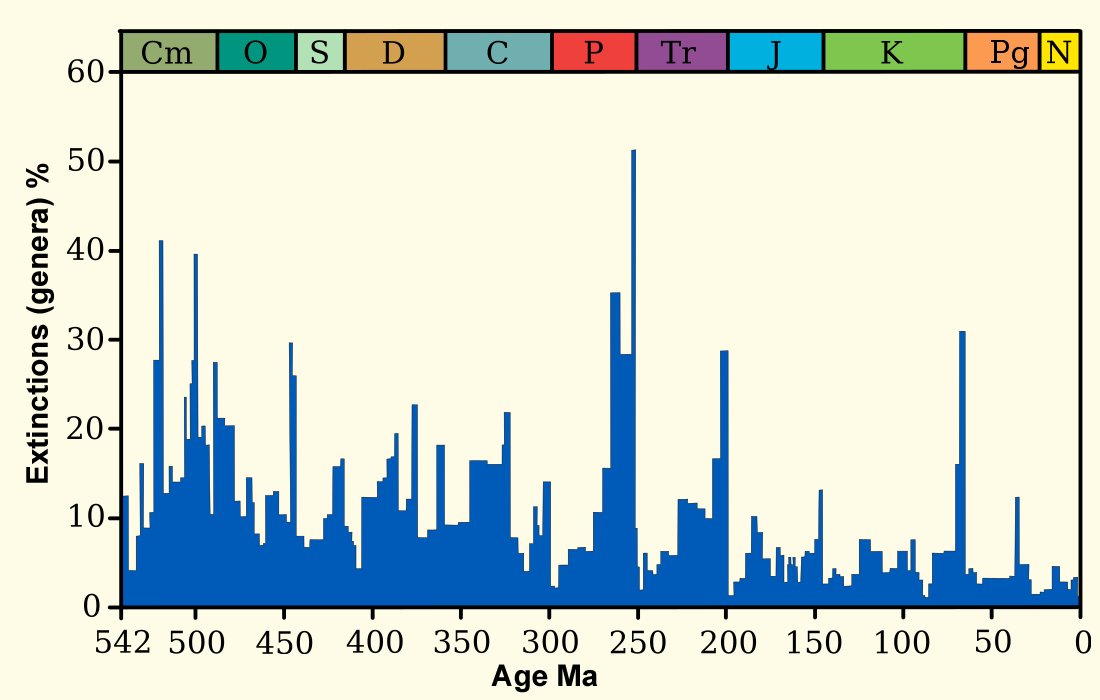

Statistical analysis of the ages of anoxic events and marine extinctions has yielded cycles of 32.5 and 26.2 Ma, those for CFBs having a 32.8 Ma periodicity. A note of caution, however: their data only cover the last 266 Ma – about one orbit of the solar system around the galactic centre. The authors attribute their interpretation of the cycles “to the Earth’s tectonic-volcanic rhythms, but the similarities with known Milankovitch Earth orbital periods and their amplitude modulations, and with known Galactic cycles, suggest that, contrary to conventional wisdom, the geological events and cycles may be paced by astronomical factors”.

Whether or not a detailed record of appropriate proxies can be extended back beyond the Late Permian, remains to be seen. The main fly-in-the-ointment is the tendency of CFB provinces to form high ground so that they are readily eroded away. Pre-Mesozoic signs of their former presence lie in basaltic dyke swarms that cut through older crystalline continental crust. The marine sedimentary record is somewhat better preserved. A search for distinctive anomalies in osmium isotopes and mercury concentrations, which are useful proxies for global productivity of basaltic magmas, will be costly. Moreover, dating will depend to a large degree on the traditional palaeontology of strata, which in Palaeozoic rocks is more difficult to calibrate precisely by absolute radiometric dating.