The genetic diversity of living humans, particularly among short, repetitive segments of DNA, is surprisingly low. As they are passed from generation to generation they have a high chance of mutation, which would be expected to create substantial differences between geographically separated populations. In the late 1990s and early 2000s some researchers attributed the absence of such gross differences to the human gene pool having been reduced to a small size in the past, thereby reducing earlier genetic variation as a result of increased interbreeding among survivors. They were able to assess roughly when such a population ‘bottleneck’ took place and the level to which the global population fell. Genetic analysis of living human populations seemed to suggest that around 74 ka ago the global human population fell to as little as 10 thousand individuals. A potential culprit was the catastrophic eruption of the Toba supervolcano in Sumatra around that time, which belched out 800 km3 of ash now found as far afield as the Greenland and Antarctic ice caps. Global surface temperature may have fallen by 10°C for several years to decades. Subsequent research has cast doubt on such a severe decline in numbers of living hummans; for instance archaeologists working in SE India found much the same numbers of stone tools above the Toba ash deposit as below it (see: Toba ash and calibrating the Pleistocene record: December 2012). Other, less catastrophic explanations for the low genetic diversity of modern humans have also been proposed. Nevertheless, environmental changes that placed huge stresses on our ancestors may repeatedly have led to such population bottlenecks, and indeed throughout the entire history of biological evolution.

An improved method of ‘back-tracking’ genetic relatedness among living populations, known as fast infinitesimal time coalescence or ‘FitCoal’, tracks genomes of individuals back to a last common ancestor. In simple language, it expresses relatedness along lineages to find branching points and, using an assumed mutation rate, estimates how long ago such coalescences probably occurred. The more lineages the further back in time FitCoal can reach and the greater the precision of the analysis. Moreover it can suggest the likely numbers of individuals, whose history is preserved in the genetics of modern people, who contributed to the gene pool at different branching points. Our genetics today are not restricted to our species for it is certain that traces of Neanderthal and Denisovan ancestry are present in populations outside of Africa. African genetics also host ‘ghosts’ of so-far unknown distant ancestors. So, the FitCoal approach may well be capable of teasing out events in human evolution beyond a million years ago, if sufficient data are fed into the algorithms. A team of geneticists based in China, Italy and the US has recently applied FitCoal to genomic sequences of 3154 individual alive today (Hu, W.and 8 others 2023. Genomic inference of a severe human bottleneck during the Early to Middle Pleistocene transition. Science, v. 381, p. 979-984; DOI I: 10.1126/science.abq7487). Their findings are startling and likely to launch controversy among their peers.

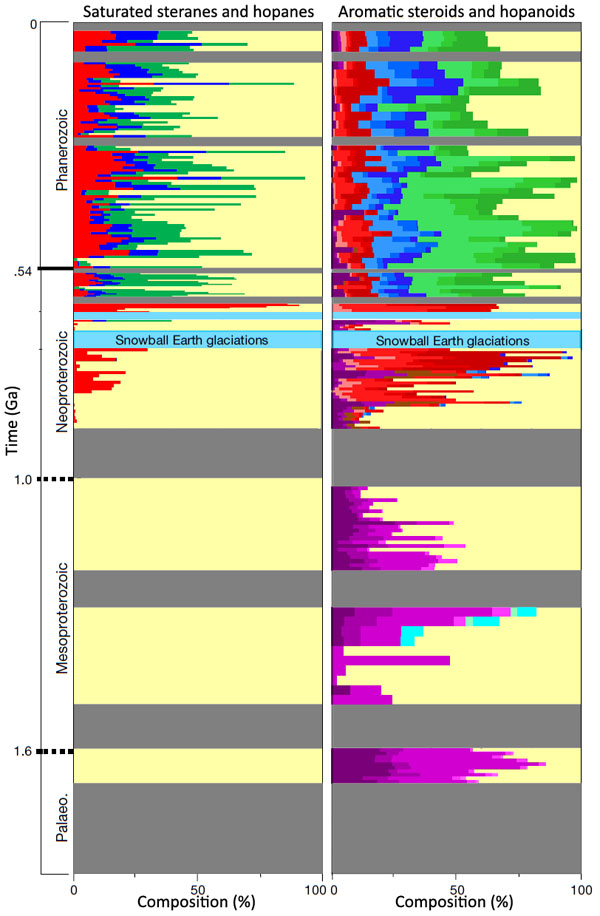

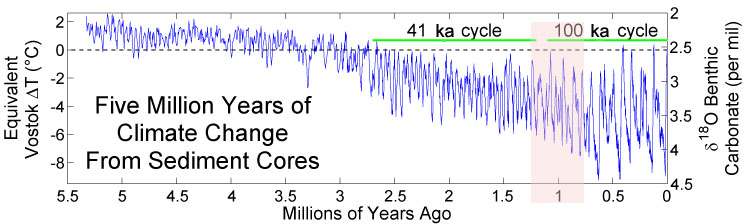

Their analyses suggest that between 930 and 813 ka ago human ancestors passed through a population bottleneck that involved only about 1300 breeding individuals. Moreover they remained at the very brink of extinction for a little under 120 thousand years. Interestingly, the genetic data are from people living on all continents, with no major differences between the analyses for geographically broad groups of people in Africa and Eurasia. Archaeological evidence, albeit sparse, suggests that ancient humans were widely spread across those two continental masses before the bottleneck event. The date range coincides with late stages of the Mid-Pleistocene climatic transition (1250 to 750 ka) during which glacial-interglacial cycles changed from 41 thousand-year periods to those that have an average duration of around 100 ka. The transition also brought with it roughly a doubling in the mean annual temperature range from the warmest parts of interglacials to the frigid glacial maxima: the world became a colder and drier place during the glacial parts of the cycles.

Genomes for Neanderthals and Denisovans suggest that they emerged as separate species between 500 and 700 ka ago. Their common ancestor, possibly Homo heidelbergensis, H. antecessor or other candidates (palaeoanthropologists habitually differ) may well have constituted the widespread population whose numbers shrank dramatically during the bottleneck. Perhaps several variants emerged because of it to become Denisovans, Neanderthals and, several hundred thousand years later, of anatomically modern humans. Yet it would require actual DNA from one or other candidate for the issue of last common ancestor for the three genetically known ‘late’ hominins to be resolved. But Hu et al. have shown a possible means of accelerated hominin evolution from which they may have emerged, at the very brink of extinction.

There is a need for caution, however. H. erectus first appeared in the African fossil record about 1.8 Ma ago and subsequently spread across Eurasia to become the most ‘durable’ of all hominin species. Physiologically they seem not to have evolved much over at least a million years, nor even culturally – their biface Acheulean tools lasted as long as they did. They were present in Asia for even longer, and apparently did not dwindle during the mid-Pleistocene transition to the near catastrophic levels as did the ancestral species for living humans. The tiny global population suggested by Hu et al. for the latter also hints that their geographic distribution had to be very limited; otherwise widely separated small bands would surely have perished over the 120 ka of the bottleneck event. Yet, during the critical period from 930 to 813 ka even Britain was visited by a small band of archaic humans who left footprints in river sediments now exposed at Happisburgh in Norfolk. Hu et al. cite the scarcity of archaeological evidence from that period – perhaps unwisely – in support of their bottleneck hypothesis. There are plenty of other gaps in the comparatively tenuous fossil and archaeological records of hominins as a whole.

The discovery of genetic evidence for this population bottleneck is clearly exciting, as is the implication that it may have been the trigger for evolution of later human species and the stem event for modern humans. Hopefully Hu et al’s work will spur yet more genetic research along similar lines, but there is an even more pressing need for field research aimed at new human fossils from new archaeological sites.

See also: Ashton, N. & Stringer, C. 2023. Did our ancestors nearly die out? Science (Perspectives), v. 381, p. 947-948; DOI: 10.1126.science.adj9484.

Ikarashi, A. 2023. Human ancestors nearly went extinct 900,000 years ago. Nature, v. 621; DOI: 10.1038/d41586-023-02712-4

Di Vicenzo, F & Manzi, G. 2023. An evolutionary bottleneck and the emergence of Neanderthals, Denisovans and modern humans. Homo heidelbergensis as the Middle Pleistocene common ancestor of Denisovans, Neanderthals and modern humans. Journal of Mediterranean Earth Sciences, v, 15, p. 161-173; DOI: 10.13133/2280-6148/18074