The largest volcanic eruption during the 2.5 million year evolution of the genius Homo, about 74 thousand years (ka) ago, formed a huge caldera in Sumatra, now filled by Lake Toba. A series of explosions lasting just 9 to 14 days was forceful enough to blast between 2,800 to 6,000 km3 of rocky debris from the crust. An estimated 800 km3 was in the form of fine volcanic ash that blanketed South Asia to a depth of 15 cm. Thin ash layers containing shards of glass from Toba occur in marine sediments beneath the Indian Ocean, the Arabian and South China Seas. Some occur as far off as sediments on the floor of Lake Malawi in southern Africa. A ‘spike’ of sulfates is present at around 74 ka in a Greenland ice core too. Stratospheric fine dust and sulfate aerosols from Toba probably caused global cooling of up to 3.5 °C over a modelled 5 years following the eruption. To make matters worse, this severe ‘volcanic winter’ occurred during a climatic transition from warm to cold caused by changes in ocean circulation and falling atmospheric CO2 concentration, known as a Dansgaard-Oeschger event.

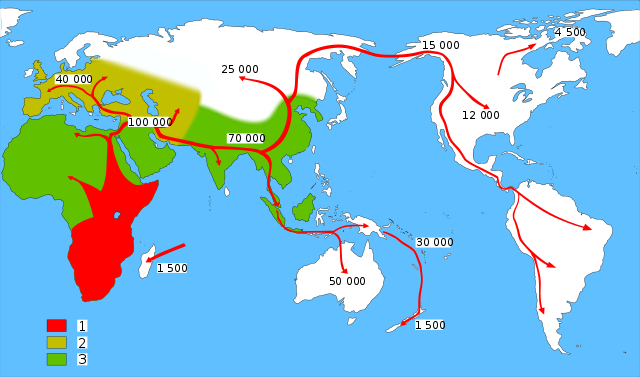

There had been short-lived migrations of modern humans out of Africa into the Levant since about 185 ka. However, studies of the mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) of living humans in Eurasia and Australasia suggest that permanent migration began about 60 ka ago. Another outcome of the mtDNA analysis is that the genetic diversity of living humans is surprisingly low. This suggests that human genetic diversity may have been sharply reduced globally roughly around the time of the Toba eruption. This implies a population bottleneck with the number of humans alive at the time to the order of a few tens of thousands (see also: Toba ash and calibrating the Pleistocene record; December 2012). Could such a major genetic ‘pruning’ have happened in Africa? Over six field seasons, a large team of geoscientists and archaeologists drawn from the USA, Ethiopia, China, France and South Africa have excavated a rich Palaeolithic site in the valley of the Shinfa River, a tributary of the Blue Nile in western Ethiopia. Microscopic studies of the sediments enclosing the site yielded glass shards whose chemistry closely matches those in Toba ash, thereby providing an extremely precise date for the human occupation of the site: during the Toba eruption itself (Kappelman, Y. and 63 others 2024. Adaptive foraging behaviours in the Horn of Africa during Toba supereruption. Nature, v. 627; DOI: 10.1038/s41586-024-07208-3).

The artifacts and bones of what these modern humans ate suggest a remarkable scenario for how they lived. Stone tools are finely worked from local basalt lava, quartz and flint-like chalcedony found in cavities in lava flows. Many of them are small, sharp triangular points, some of which show features consistent with their use as projectile tips that fractured on impact; they may be arrowheads, indeed the earliest known. Bones found at the site are key pointers to their diet. They are from a wide variety of animal, roughly similar to those living in the area at present: from monkeys to giraffe, guinea fowl to ostrich, and even frogs. There are remains of many fish and freshwater molluscs. Although there are no traces of plant foods, clearly those people who loved through the distant effects of Toba were well fed. Although a period of global cooling may have increased aridity at tropical latitudes in Africa, the campers were able to devise efficient strategies to obtain victuals. During wet seasons they lived off terrestrial prey animals, and during the driest times ate fish from pools in the river valley. These are hardly conditions likely to devastate their numbers, and the people seem to have been technologically flexible. Similar observations were made at the Pinnacle Point site in far-off South Africa in 2018, where Toba ash is also present. Both sites refute any retardation of human cultural progress 74 ka ago. Rather the opposite: people may have been spurred to innovation, and the new strategies may have allowed them to migrate more efficiently, perhaps along seasonal drainages. In this case that would have led them or their descendants to the Nile and a direct route to Eurasia; along ‘blue highway’ corridors as Kappelman et al. suggest.

Yet the population bottleneck implied by mtDNA analyses is only vaguely dated: it may have been well before or well after Toba. Moreover, there is a 10 ka gap between Toba and the earliest accurately dated migrants who left Africa – the first Australians at about 65 ka. However, note that there is inconclusive evidence that modern humans may have occupied Sumatra by the time of the eruption. Much closer to the site of the eruption in southeast India, stone artifacts have been found below and above the 74 ka datum marked by the thick Toba Ash. Whether these were discarded by anatomically modern humans or earlier migrants such as Homo erectus remains unresolved. Either way, at that site there is no evidence for any mass die-off, even though conditions must have been pretty dreadful while the ash fell. But that probably only lasted for little more than a month. If the migrants did suffer very high losses to decrease the genetic diversity of the survivors, it seems just as likely to have been due to attrition on an extremely lengthy trek, with little likelihood of tangible evidence surviving. Alternatively, the out-of-Africa migrants may have been small in number and not fully representative of the genetic richness of the Africans who stayed put: a few tens of thousand migrants may not have been very diverse from the outset.