In 1961 ten scientists interested in a search for extra-terrestrial intelligence met at Green Bank, West Virginia, USA, none of whom were geologists or palaeontologists. The participants called themselves “The Order of the Dolphin”, inspired by the thorny challenge of discovering how small cetaceans communicated: still something of a mystery. To set the ball rolling, Frank Drake an American astrophysicist and astrobiologist, proposed an algorithm aimed at forecasting the number of planets elsewhere in our galaxy on which ‘active, communicative civilisations’ (ACCs) might live. The Drake Equation is formulated as:

ACCs = R* · fp · ne · fl · fi · fc · L

where R* = number of new stars formed per year, fp = the fraction of stars with planetary systems, ne = the average number of planets that could support life (habitable planets) per planetary system, fl = the fraction of habitable planets that develop primitive life, fi = the fraction of planets with life that evolve intelligent life and civilizations, fc = the fraction of civilizations that become ACCs, L = the length of time that ACCs broadcast radio into space. A team of then renowned scientists from several disciplines discussed what numbers to attach to these parameters. Their ‘educated guesses’ were: R* – one star per year; fp – one fifth to one half of all stars will have planets; ne – 1 to 5 planets per planetary system will be habitable; of which 100% will develop life (fl) and 100% (fi) will eventually develop intelligent life and civilisations; of those civilisations 10 to 20 % (fc) will eventually develop radio communications; which will survive for between a thousand years and 100 Ma (L). Acknowledging the great uncertainties in all the parameters, Drake inferred that between 103 and 108 ACCs exist today in the Milky Way, which is ~100 light years across and contains 1 to 4 x 1011 stars).

Today the values attached to the parameters and the outcomes seem absurdly optimistic to most people, simply because, despite 4 decades of searching by SETI there have been no signs of intelligible radio broadcasts from anywhere other than Earth and space probes launched from here. This is humorously referred to as the Fermi Paradox. There are however many scientists who still believe that we are not alone in the galaxy, and several have suggested reasons why nothing has yet been heard from ACCs. Robert Stern of the University of Texas (Dallas), USA and Taras Gerya of ETH-Zurich, Switzerland have sought clues from the history of life on Earth and that of the inorganic systems from which it arose and in which it has evolved that bear on the lack of any corrigible signals in the 63 years since the Drake Equation (Stern, R.J & Gerya, T.V. 2024. The importance of continents, oceans and plate tectonics for the evolution of complex life: implications for finding extraterrestrial civilizations. Nature (Scientific Reports), v. 14, article 8552; DOI: 10.1038/s41598-024-54700-x – definitely worth reading). Of course, Stern and Gerya too are fascinated by the scientific question as to whether or not there are ‘active, communicative civilisations’ elsewhere in the cosmos. Their starting point is that the Drake Equation is either missing some salient parameters, or that those it includes are assigned grossly optimistic magnitudes.

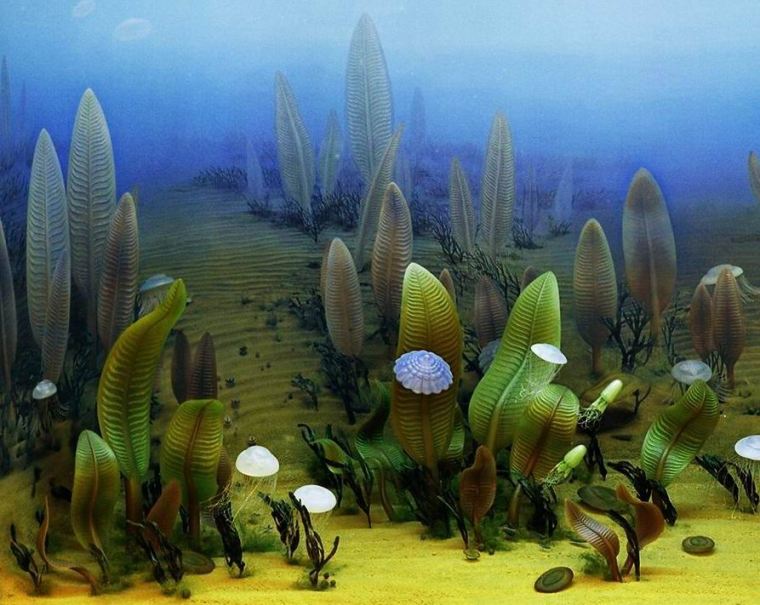

Life seems to have been present on Earth 3.8 Ga ago but multicelled animals probably arose only in the Late Neoproterozoic since 1.0 Ga ago. So here it has taken a billion years for their evolution to achieve terrestrial ACC-hood. Stern and Gerya address what processes favour life and its rapid evolution. Primarily, life depends on abundant liquid water: i.e. on a planet within the ‘Goldilocks Zone’ around a star. The authors assume a high supply of bioactive compounds – organic carbon, ammonium, ferrous iron and phosphate to watery environments. Phosphorus is critical to their scenario building. It is most readily supplied by weathering of exposed continental crust, but demands continual exposure of fresh rock by erosion and river transport to maintain a steady supply to the oceans. Along with favourable climatic conditions, that can only be achieved by an oxidising environment that followed the Great Oxidation Event (2.4 to 2.1 Ga) and continual topographic rejuvenation by plate tectonics.

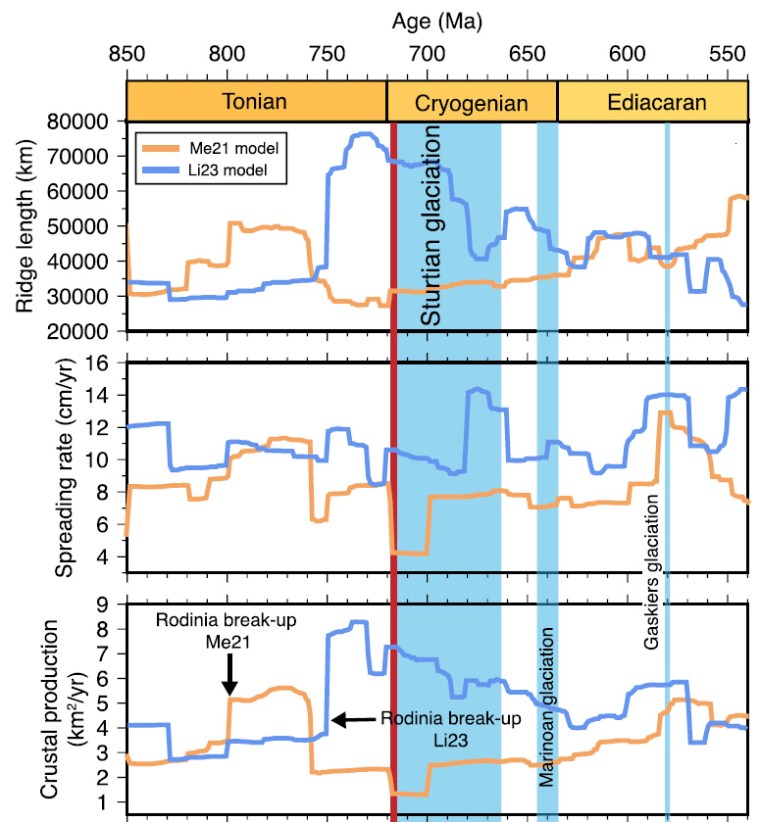

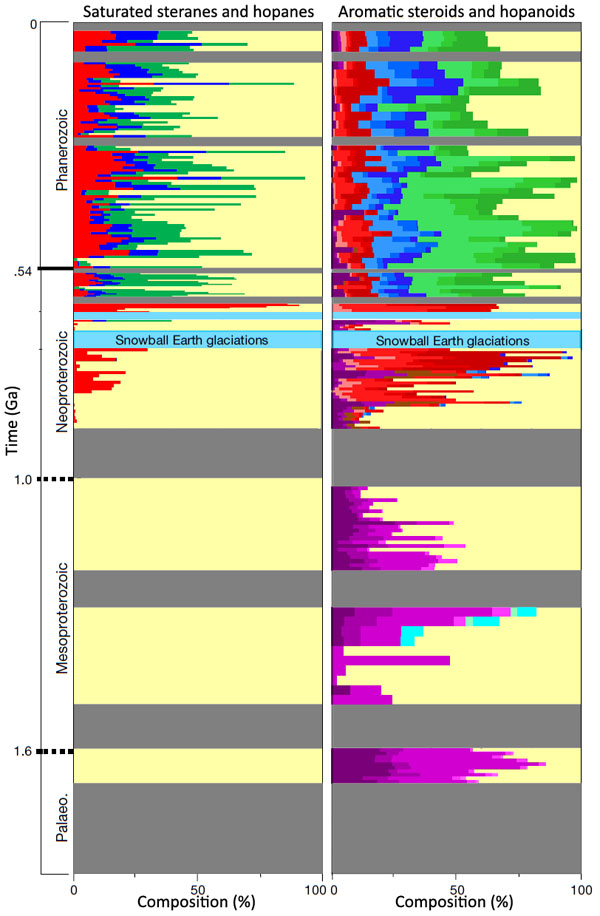

A variety of Earth-logs posts have discussed various kinds of evidence for the likely onset of plate tectonics, largely focussing on the Hadean and Archaean. Stern and Gerya prefer the Proterozoic Eon that preserves more strands of relevant evidence, from which sea-floor spreading, subduction and repeated collision orogenies can confidently be inferred. All three occur overwhelmingly in Neoproterozoic and Phanerozoic times. Geologists often refer to the whole of the Mesoproterozoic and back to about 2.0 Ga in the Palaeoproterozoic as the ‘Boring Billion’ during which carbon isotope data suggest very little change in the status of living processes: they were present but nothing dramatic happened after the Great Oxidation Event. ‘Hard-rock’ geology also reveals far less passive extensional events that indicate continental break-up and drift than occur after 1.0 Ga and to the present. It also includes a unique form of magmatism that formed rocks dominated by sodium-rich feldspar (anorthosites) and granites that crystallised from water-poor magmas. They are thought to represent build-ups of heat in the mantle unrelieved by plate-tectonic circulation. Before the ‘Boring Billion’ such evidence as there is does point to some kind of plate motions, if not in the modern style.

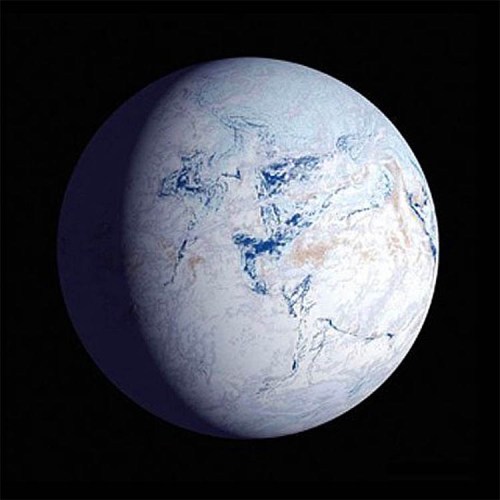

Stern and Gerya conclude that the ‘Boring Billion’ was dominated by relative stagnation in the form of lid tectonics. They compare the influence of stagnant ‘lid’ tectonics on life and evolution with that of plate tectonics in terms of: bioactive element supply; oxygenation; climate control; habitat formation; environmental pressure (see figure). In each case single lid tectonics is likely to retard life and evolution, whereas plate tectonics stimulates them as it has done from the time of Snowball Earth and throughout the Phanerozoic. Only one out of 8 planets that orbit the sun displays plate tectonics and has both oceans and continents. Could habitable planets be a great deal rarer than Drake and his pals assumed? [look at exoplanets in Wikipedia] Whatever, Stern and Gerya suggest that the seemingly thwarted enthusiasm surrounding the Drake Equation needs to be tempered by the addition of two new terms: the fraction of habitable exoplanets with significant continents and oceans (foc)and the fraction of them that have experienced plate tectonics for at least half a billion years (fpt). They estimate foc to be on the order of 0.0002 to 0.01, and suggest a value for fpt of less than 0.17. Multiplied together yields value between less than 0.00003 and 0.002. Their incorporation in the Drake Equation drastically reduces the potential number of ACCs to between <0.006 and <100,000, i.e. to effectively none in the Milky Way galaxy rising to a still substantial number

There are several other reasons to reject such ‘ball-parking’ cum ‘back-of-the-envelope’ musings. For me the killer is that biological evolution can never be predicted in advance. What happened on our home world is that the origin and evolution of life have been bound up with the unique inorganic evolution of the Solar System and the Earth itself over more than 4.5 billion years. That ranges in magnitude from the early collision with another, Mars-sized world that reset the proto-Earth’s geochemistry and created a large moon whose gravity has cycled the oceans through tides and changed the length of the day continually for almost the whole of geological history. At least once, at the end of the Cretaceous Period, a moderately sized asteroid in unstable orbit almost wiped out life at an advanced stage in its evolution. During the last quarter billion years internally generated geological forcing mechanisms have repeatedly and seriously stressed the biosphere in roughly 36 Ma cycles (Boulila, S. et al. 2023. Earth’s interior dynamics drive marine fossil diversity cycles of tens of millions of years. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, v. 120 article e2221149120; DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2221149120). Two outcomes were near catastrophic mass extinctions, at the ends of the Permian and Triassic Periods, from which life struggled to continue. As well as extinctions, such ‘own goals’ reset global ecosystems repeatedly to trigger evolutionary diversification based on the body plans of surviving organisms.

Such unique events have been going on for four billion years, including whatever triggered the Snowball Earth episodes that accompanied the Great Oxygenation Event around 2.4 Ga and returned to coincide with the rise of multicelled animals during the Cryogenian and Ediacaran Periods of the Late Neoproterozoic. For most of the Phanerozoic a background fibrillation of gravitational fields in the Solar System has occasionally resulted in profound cycling between climatic extremes and their attendant stresses on ecosystems and their occupants. The last of these coincided with the evolution of humanity: the only creator of an active, communicative civilisation of which we know anything. But it took four billion years of a host of diverse vagaries, both physical and biological to make such a highly unlikely event possible. That known history puts the Drake Equation firmly in its place as the creature of a bunch of self-publicising and regarding, ambitious academics who in 1961 basically knew ‘sweet FA’. I could go on … but the wealth of information in Stern and Gerya’s work is surely fodder for a more pessimistic view of other civilisations in the cosmos.

Someone – I forget who – provided another, very practical reason underlying the lack of messages from afar. It is not a good idea to become known to all and sundry in the galaxy, for fear that others might come to exploit, enslave and/or harvest. Earth is still in a kind of imperialist phase from which lessons could be drawn!