Assigning human fossils older than around 250 ka to different groups of the genus Homo depends entirely on their physical features. That is because ancient DNA has yet to be found and analysed from specimens older than that. The phylogeny of older human remains is also generally restricted to the bones that make up their heads; 21 that are fixed together in the skull and face, plus the moveable lower jaw or mandible. Far more teeth than crania have been discovered and considerable weight is given to differences in human dentition. Teeth are not bones, but they are much more durable, having no fibrous structure and vary a great deal. The main problem for palaeoanthropologists is that living humans are very diverse in their cranial characteristics, and so it is reasonable to infer that all ancient human groups were characterised by such polymorphism, and may have overlapped in their physical appearance. A measure of this is that assigning fossils to anatomically modern humans, i.e. Homo sapiens, relies to a large extent on whether or not their lower mandible juts out to define a chin. All earlier hominins and indeed all other living apes might be regarded as ‘chinless wonders’! This pejorative term suggests dim-wittedness to most people, and anthropologists have had to inure themselves to such crude cultural conjecture.

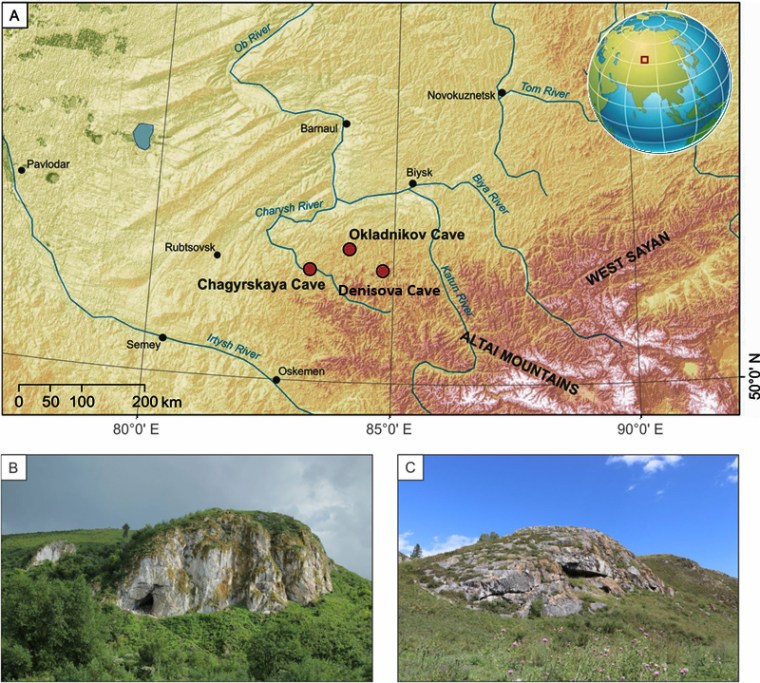

The extraction, sequencing and comparison of ancient DNA from human fossils since 2010 has revealed that three distinct human species coexisted and interbred in Eurasia. Several well preserved examples of ancient Neanderthals and anatomically modern humans (AMH) have had their DNA sequenced, but a Denisovan genome has only emerged from a few bone fragments from the Denisova Cave in western Siberia. Whereas Neanderthals have well-known robust physical characters, until 2025 palaeoanthropologists had little idea of what Denisovans may have looked like. Then proteins and, most importantly, mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) were extracted from a very robust skull found around 1931 in Harbin, China, dated at 146 ka. Analysis of the mtDNA and proteins, from dental plaque and bone respectively, reveal that the Harbin skull is likely to be that of a Denisovan. Previously it had been referred to as Homo longi, or ‘Dragon Man’, along with several other very robust Chinese skulls of a variety of ages.

The sparse genetic data have been used to suggest the times when the three different coexisting groups diverged. DNA in Y chromosomes from Denisovans and Neanderthals suggest that the two lineages split from a common ancestor around 700 ka ago, whereas Neanderthals and modern humans diverged genetically at about 370 ka. Yet the presence of sections of DNA from both archaic groups in living humans and the discovery that a female Neanderthal from Denisova cave had a Neanderthal mother and a Denisovan father reveals that all three were interfertile when they met and interacted. Such admixture events clearly have implications for earlier humans. There are signs of at least 6 coexisting groups as far back as the Middle Pleistocene (781 to 126 ka), referred to by some as the ‘muddle in the middle’ because such an association has increasingly mystified palaeoanthropologists. A million-year-old, cranium found near Yunxian in Hubei Province, China, distorted by the pressure of sediments in which it was buried, has been digitally reconstructed.

This reconstruction encouraged a team of Chinese scientists, together with Chris Stringer of the UK Museum of Natural History, to undertake a complex statistical study of the Yunxian cranium. Their method compares it with anatomical data for all members of the genus Homo from Eurasia and Africa, i.e. as far back as the 2.4 Ma old H. habilis (Xiabo Feng and 12 others 2025. The phylogenetic position of the Yunxian cranium elucidates the origin of Homo longi and the Denisovans. Science, v. 389, p. 1320-1324; DOI: 10.1126/science.ado9202). The study has produced a plausible framework that suggests that the five large-brained humans known from 800 ka ago – Homo erectus (Asian), H. heidelbergensis, H. longi (Denisovans), H. sapiens, and H. neanderthalensis – began diverging from one another more than a million years ago. The authors regard the Yuxian specimen as an early participant in that evolutionary process. The fact that at least some remained interfertile long after the divergence began suggests that it was part of the earlier human evolutionary process. It is also possible that the repeated morphological divergence may stem from genetic drift. That process involves small populations with limited genetic diversity that are separated from other groups, perhaps by near-extinction in a population bottleneck or as a result of the founder effect when a small group splits from a larger population during migration. The global population of early humans was inevitably very low, and migrations would dilute and fragment each group’s gene pool.

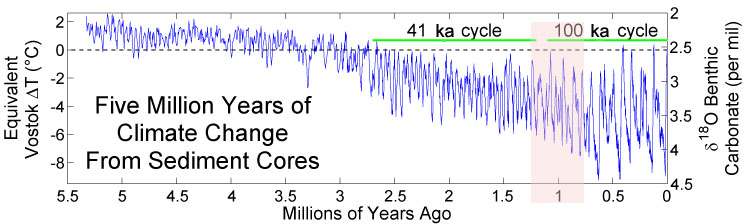

The earliest evidence for migration of humans out of Africa emerged from the discovery of five 1.8 Ma old crania of H. erectus at Dmanisi to the east of the Black Sea in Georgia. similar archaic crania have been found in eastern Eurasia, especially China, at various localities with Early- to Middle Pleistocene dates. The earliest European large-brained humans – 1.2 to 0.8 Ma old H. antecessor from northern Spain – must have migrated a huge distance from either Africa or from eastern Eurasia and may have been a product of the divergence-convergence evolutionary framework suggested by Xiabo Feng and colleagues. Such a framework implies that even earlier members of what became the longi, heidelbergensis, neanderthalensis, and sapiens lineages may await either recognition or discovery elsewhere. But the whole issue raises questions about the widely held view that Homo sapiens first appeared 300 ka ago in North Africa and then populated the rest of that continent. Was that specimen a migrant from Eurasia or from elsewhere in Africa? The model suggested by Xiabo Feng and colleagues is already attracting controversy, but that is nothing new among palaeoanthropologists. Yet it is based on cutting edge phylogeny derived from physical characteristics of hominin fossils: the traditional approach by all palaeobiologists. Such disputes cannot be resolved without ancient DNA or protein assemblages. But neither is a completely hopeless task, for Siberian mammoth teeth have yielded DNA as old as 1.2 Ma and the record is held by genetic material recovered from sediments in Greenland that are up to 2.1 Ma old. The chances of pushing ancient human DNA studies back to the ‘muddle’ in the Middle Pleistocene depend on finding human fossils at high latitudes in sediments of past glacial maxima or very old permafrost, for DNA degrades more rapidly as environmental temperature rises.

See also: Natural History Museum press release. Analysis of reconstructed ancient skull pushes back our origins by 400,000 years to more than one million years ago. 25 September 2025; Bower, B. 2025. An ancient Chinese skull might change how we see our human roots. ScienceNews, 25 September 2025; Ghosh, P. 2025. Million-year-old skull rewrites human evolution, scientists claim. The Guardian, 25 September 2025