February 2024 was a notable month for discoveries about ancient technology: first that of an ancient tool probably used in rope making and now signs of the use of a composite ‘plastic’ material in stone-tool hafts. Both are from Neanderthal sites in France, the first dated around 52 to 41 ka and the second in the Le Moustier rock shelters of the Dordogne – the type locality for the Mousterian culture associated with Neanderthals (Schmidt, P. et al. 2024. Ochre-based compound adhesives at the Mousterian type-site document complex cognition and high investment. Science Advances, v. 10, article ead10822; DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adl0822), dated at around 56 to 40 ka. The second discovery resulted from the first detailed analysis of unstudied artifacts unearthed from Le Moustier in 1907 by Swiss archaeologist Otto Hauser that had been tucked away in a Berlin Museum.

Patrick Schmidt of the University of Tubingen in Germany and colleagues from Germany, the US and Kazakhstan identified stone artifacts that show traces of red and yellow colorants. At first sight it could be suggested that they are decorations of some kind. However, they coat only parts of the stone flakes and are sharply distinct from the fresh rock surface and the sharpest edges. Another feature discovered during chemical analysis is that the colour is due to iron hydroxides (goethite) but this ochre is mixed with natural bitumen: the coating is a composite of an adhesive and filler not far different from what can be purchased in any hardware store.

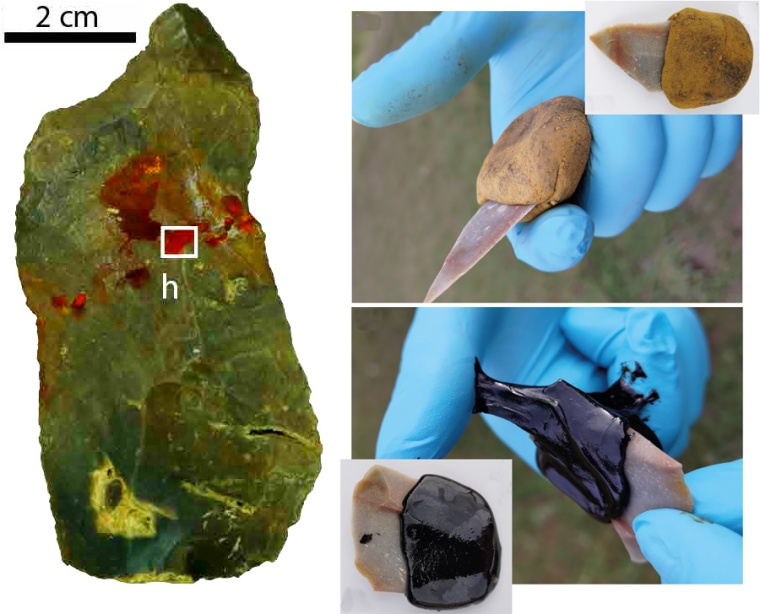

The authors tested the properties of the mixtures against those of bitumen alone – an adhesive known to have been used along with various tree resins to haft blades to spears in earlier times. In particular they examined the results of ‘cooking’ the substances. Whether unheated or ‘cooked’ a mixture of ochre and bitumen is up to three times stronger than pure bitumen. A further advantage is that the mixed ingredients are not sticky when cooked and cooled, whereas bitumen remains sticky, as the illustration clearly shows. Anyone who has handled a stone blade realises how sharp they are, and not just around the cutting edges. So Schmidt and colleagues tried to use the composite material as a protective handle when stone flake tools were gripped for cutting or carving. The composite handles worked well on scrapers and blades, even in the softer, ‘uncooked’ form

Similar composite adhesives are known from older sites in Africa associated with anatomically modern humans, but not for this particular, very practical use. It is perhaps possible that the use of bitumen mixed with ochre was brought into Europe by AMH migrants and adopted by Neanderthals who came into contact with them. Yet the limestones of the Dordogne valley yield both bitumen in liquid and solid forms, and ochers are easily found because of their striking colours. Long exposure of petroleum seeps drives off lighter petroleum compounds to leave solid residues that can be melted easily to tarry consistency. So there is every reason to believe that Neanderthals developed this technology unaided. As Schmidt has commented, “Compound adhesives are considered to be among the first expressions of the modern cognitive processes that are still active today”.