Four out of six mass extinctions that ravaged life on Earth during the last 300 Ma coincided with large igneous events marked by basaltic flood volcanism. But not all such bursts of igneous activity match significant mass extinctions. Moreover, some rapid rises in the rate of extinction are not clearly linked to peaks in igneous activity. Another issue in this context is that ‘kill mechanisms’ are generally speculative rather than based on hard data. Large igneous events inevitably emit very large amounts of gases and dust-sized particulates into the atmosphere. Carbon dioxide, being a greenhouse gas, tends to heat up the global climate, but also dissolves in seawater to lower its pH. Both global warming and more acidic oceans are possible ‘kill mechanisms’. Volcanic emission of sulfur dioxide results in acid rain and thus a decrease in the pH of seawater. But if it is blasted into the stratosphere it combines with oxygen and water vapour to form minute droplets of sulfuric acid. These form long-lived haze, which reflects solar energy beck into space. Such an increased albedo therefore tends to cool the planet and create a so-called ‘volcanic winter’. Dust that reaches the stratosphere reduces penetration of visible light to the surface, again resulting in cooling. But since photosynthetic organisms rely on blue and red light to power their conversion of CO2 and water vapour to carbohydrates and oxygen, these primary producers at the base of the marine and terrestrial food webs decline. That presents a fourth kill mechanism that may trigger mass extinction on land and in the oceans: starvation.

Palaeontologists have steadily built up a powerful case for occasional mass extinctions since fossils first appear in the stratigraphic record of the Phanerozoic Eon. Their data are simply the numbers of species, genera and families of organisms preserved as fossils in packages of sedimentary strata that represent roughly equal ‘parcels’ of time (~10 Ma). Mass extinctions are now unchallengeable parts of life’s history and evolution. Yet, assigning specific kill mechanisms involved in the damage that they create remains very difficult. There are hypotheses for the cause of each mass extinction, but a dearth of data that can test why they happened. The only global die-off near hard scientific resolution is that at the end of the Cretaceous. The K-Pg (formerly K-T) event has been extensively covered in Earth-logs since 2000. It involved a mixture of global ecological stress from the Deccan large igneous event spread over a few million years of the Late Cretaceous, with the near-instantaneous catastrophe induced by the Chicxulub impact, with a few remaining dots and ticks needed on ‘i’s and ‘t’s. Other possibilities have been raised: gamma-ray bursts from distant supernovae; belches of methane from the sea floor; emissions of hydrogen sulfide gas from seawater itself during ocean anoxia events; sea-level changes etc.

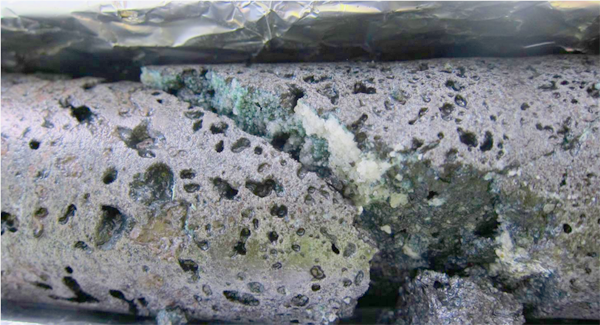

The mass extinction that ended the Triassic (~201 Ma) coincides with evidence for intense volcanism in South and North America, Africa and southern Europe, then at the core of the Pangaea supercontinent. Flood basalts and large igneous intrusions – the Central Atlantic Magmatic Province (CAMP) – began the final break-up of Pangaea. The end-Triassic extinction deleted 34% of marine genera. Marine sediments aged around 201 Ma reveal a massive shift in sulfur and carbon isotopes in the ocean that has been interpreted as a sign of acute anoxia in the world’s oceans, which may have resulted in massive burial of oxygen-starved marine animal life. However, there is no sign of Triassic, carbon-rich deep-water sediments that characterise ocean anoxia events in later times. But it is possible that bacteria that use the reduction of sulfate (SO42-) to sulfide (S2-) ions as an energy source for them to decay dead organisms, could have produced the sulfur isotope ‘excursion’. That would also have produced massive amounts of highly toxic hydrogen sulfide gas, which would have overwhelmed terrestrial animal life at continental margins. The solution ofH2S in water would also have acidified the world’s oceans.

Molly Trudgill of the University of St Andrews, Scotland and colleagues from the UK, France, the Netherlands, the US, Norway, Sweden and Ireland set out to test the hypothesis of end-Triassic oceanic acidification (Trudgill, M. and 24 others 2025. Pulses of ocean acidification at the Triassic–Jurassic boundary. Nature Communications, v. 16, article 6471; DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-61344-6). The team used Triassic fossil oysters from before the extinction time interval. Boron-isotope data from the shells are a means of estimating variations in the pH of seawater. Before the extinction event the average pH in Triassic seawater was about the same as today, at 8.2 or slightly alkaline. By 201 Ma the pH had shifted towards acidic conditions by at least 0.3: the biggest detected in the Phanerozoic record. One of the most dramatic changes in Triassic marine fauna was the disappearance of reef limestones made by the recently evolved modern corals on a vast scale in the earlier Triassic; a so-called ‘reef gap’ in the geological record. That suggests a possible analogue to the waning of today’s coral reefs that is thought to be a result of increased dissolution of CO2 in seawater and acidification, related to global greenhouse warming. Using the fossil oysters, Trudgill et al. also sought a carbon-isotope ‘fingerprint’ for the source of elevated CO2, finding that it mainly derived from the mantle, and was probably emitted by CAMP volcanism. So their discussion centres mainly on end-Triassic ocean acidification as an analogy for current climate change driven by CO2 largely emitted by anthropogenic burning of fossil fuels. Nowhere in their paper do they mention any role for acidification by hydrogen sulfide emitted by massive anoxia on the Triassic ocean floor, which hit the scientific headlines in 2020 (see earlier link).