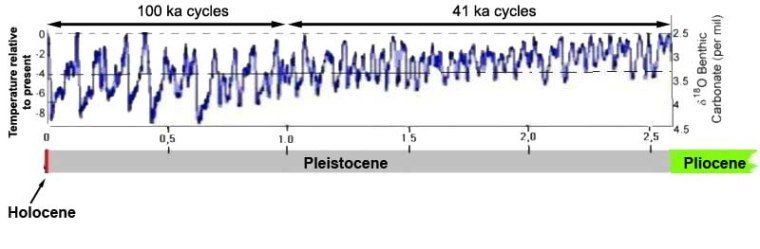

Before about a million years ago the Earth’s overall climate repeatedly swung from warm to cool roughly every 41 thousand years. This cyclicity is best shown by the variation of oxygen isotopes in sea-floor sediments. That evidence stems from the tendency during evaporation at the ocean surface for isotopically light oxygen (16O) in seawater to preferentially enter atmospheric water vapour relative to 18O. During cool episodes more water vapour that falls as snow at high latitudes fails to melt, so that glaciers grow. Continental ice sheets therefore extract and store 16O so that the proportion of the heavier 18O increases in the oceans. This shift shows up in the calcium carbonate (CaCO3) shells of surface-dwelling organisms whose shells are preserved in sea-floor sediment. When the climate warms, the ice sheets melt and return the excess of 16O back to ocean-surface water, again marked by changed oxygen isotope proportions in plankton shells. The first systematic study of sea-floor oxygen isotopes over time revolutionised ideas about ancient climates in much the same way as sea-floor magnetic stripes revealed the existence of plate tectonics. Both provided incontrovertible explanations for changes observed in the geological record. In the case of oxygen isotopes climatic cyclicity could be linked to changes in the Earth’s orbital and rotational behaviour: the Milankovich Effect.

The 41 ka cycles reflect periodic changes in the angle of the Earth’s rotational axis (obliquity), which have the greatest effect on how much solar heating occurs at high latitudes. However, between about 1200 and 600 ka the fairly regular, moderately intense 41 ka climate cycles shifted to more extreme, complex and longer 100 ka cycles at the ‘Mid-Pleistocene Transition’ (MPT). They crudely match cyclical variations in the shape of Earth’s orbit (eccentricity), but that has by far the least influence over seasonal solar heating. Moreover, modelling of the combined astronomical climate influences through the transition show little, if any, sign of any significant change in external climatic forcing. Thirty years of pondering on this climatic enigma has forced climatologists to wonder if the MPT was due to some sort of change in the surface part of the Earth system itself.

There are means of addressing the general processes at the Earth’s surface and how they may have changed by using other aspects of sea-floor geochemistry (Yehudai, M. and 8 others 2021. Evidence for a Northern Hemispheric trigger of the 100,000-y glacial cyclicity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, v. 118, article e2020260118; DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2020260118). For instance the ratio between the abundance of the strontium isotope 87Sr to that of 86Sr in marine sediments tells us about the progress of continental weathering around a particular ocean basin. The 87Sr/ 86Sr ratio is higher in rocks making up the bulk of the crystalline continental crust than that in basalts of the oceanic crust. That ratio is currently uniform throughout all ocean water. During the Cenozoic Era the ratio steadily increased in sea-floor sediments, reflecting the continual weathering and erosion of the continents. In the warm Pliocene (5.3 to 2.8 Ma) 87Sr/ 86Sr remained more or less constant, but began increasing again at the start of the Pleistocene with the onset of glaciation in the Northern Hemisphere. At about 1450 ka it began to increase more rapidly suggesting increased weathering, and then settled back to its earlier Pleistocene rate after 1100 ka. Another geochemical contrast between the continental and oceanic crust lies in the degree to which the ratio of two isotopes of neodymium (143Nd/144Nd) in rocks deviates from that in the Earth’s mantle – modelled from meteorite geochemistry – a measure signified by ЄNd. Magmatic rocks and young continental rocks have positive ЄNd values, but going back in time continental crust has increasingly negative ЄNd.

Yehudai et al analysed cores from deep-sea sediments that had been drilled between 41°N and 43°S in the Atlantic Ocean floor. They targeted layers designated as glacial and interglacial from their oxygen isotope geochemistry at different levels in the cores to check how ЄNd varied with time. The broad variations within each core look much the same, although at increasingly negative values from south to north, except in one case. The data from the most northerly Atlantic core show far more negative values of ЄNd, in both glacial and interglacial layers at around 950 ka ago, than do cores further to the south. The authors interpret this anomaly as showing a sudden increase in the amount of very old continental rocks – with highly negative ЄNd – that had become exposed at and ground from the base of the great northern ice sheets of North America, Greenland and Scandinavia. At present, the shield areas where the great ice sheets occurred until about 11 ka are almost entirely crystalline Precambrian basement, including the most ancient rocks that are known. Although broadly speaking the shields now have low relief, they are extremely rugged terrains of knobbly basement outcrops and depressions filled with millions of lakes. In the earlier Cenozoic they were covered by younger sedimentary rocks and soils formed by deep weathering, with less-negative ЄNd values. The authors conclude that around 950 ka that younger cover had largely been removed by glacial every every 41 ka or so since about 2.6 Ma ago, when glaciation of the Northern Hemisphere began.

So what follows from that ЄNd anomaly? Yehudai et al suggest that in earlier Pleistocene times each successive ice sheet rested on soft rock; i.e. their bases were well lubricated. As a result, glaciers quickly reached the coast to break up and melt as icebergs drifted south. Exposure of the deeper, very resistant crystalline basement resulted in much more rugged base, as can be seen in northern Canada and Scandinavia today. Friction at their bases suddenly increased, so that much more ice was able to build up on the great shields surrounding the Arctic Ocean than had previously been possible. Shortly after 950 ka the sea-floor cores also reveal that deep ocean circulation weakened significantly in the following 100 ka. The influence on climate of regular, 41 ka changes in the tilt of the Earth’s rotational axis could therefore not be sustained in the later Pleistocene. The ice sheets could neither melt nor slide into the sea sufficiently quickly; indeed, bigger and more durable ice sheets would reflect away more solar heating than was previously possible as glacial gave way to interglacial. The 41 ka astronomical ‘pacemaker’ still operated, but ineffectually. A new and much more complex climate cyclicity set in. Insofar as climate change became stabilised, an overall ~100 ka pulsation emerged. Whether or not this fortuitously had the same pace as the weak influence of Earth’s changing orbital eccentricity remains to be addressed. The climate system just might be too complicated and sensitive for us ever to tell: it may even have little relevance in a climatically uncertain future.

See also: Why did glacial cycles intensify a million years ago? Science Daily, 8 November 2021.