In March 1989 an asteroid half a kilometre across passed within 500 km of the Earth at a speed of 20 km s-1. Making some assumptions about its density, the kinetic energy of this near miss would have been around 4 x 1019 J: a million times more than Earth’s annual heat production and humanity’s annual energy use; and about half the power of detonating every thermonuclear device ever assembled. Had that small asteroid struck the Earth all this energy would have been delivered in a variety of forms to the Earth System in little more than a second – the time it would take to pass through the atmosphere. The founder of “astrogeology” and NASA’s principal geological advisor for the Apollo programme, the late Eugene Shoemaker, likened the scenario to a ‘small hill falling out of the sky’. (Read a summary of what would happen during such an asteroid strike). But that would have been dwarfed by the 10 to 15 km impactor that resulted in the ~200 km wide Chicxulub crater and the K-Pg mass extinction 66 Ma ago. Evidence has been assembled for Earth having been struck during the Archaean around 3.6 billion years (Ga) ago by an asteroid 200 to 500 times larger: more like four Mount Everests ‘falling out of the sky’ (Drabon, N. et al. 2024. Effect of a giant meteorite impact on Paleoarchean surface environments and life. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, v. 121, article e2408721121; DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2408721121

In fact the Palaeoarchaean Era (3600 to 3200 Ma) was a time of multiple large impacts. Yet their recognition stems not from tangible craters but strata that contain once glassy spherules, condensed from vaporised rock, interbedded with sediments of Palaeoarchaean ‘greenstone belts’ in Australia and South Africa (see: Evidence builds for major impacts in Early Archaean; August 2002, and Impacts in the early Archaean; April 2014), some of which contain unearthly proportions of different chromium isotopes (see: Chromium isotopes and Archaean impacts; March 2003). Compared with the global few millimetres of spherules at the K-Pg boundary, the Barberton greenstone belt contains eight such beds up to 1.3 m thick in its 3.6 to 3.3 Ga stratigraphy. The thickest of these beds (S2) formed by an impact at around 3.26 Ga by an asteroid estimated to have had a mass 50 to 200 times that of the K-Pg impactor.

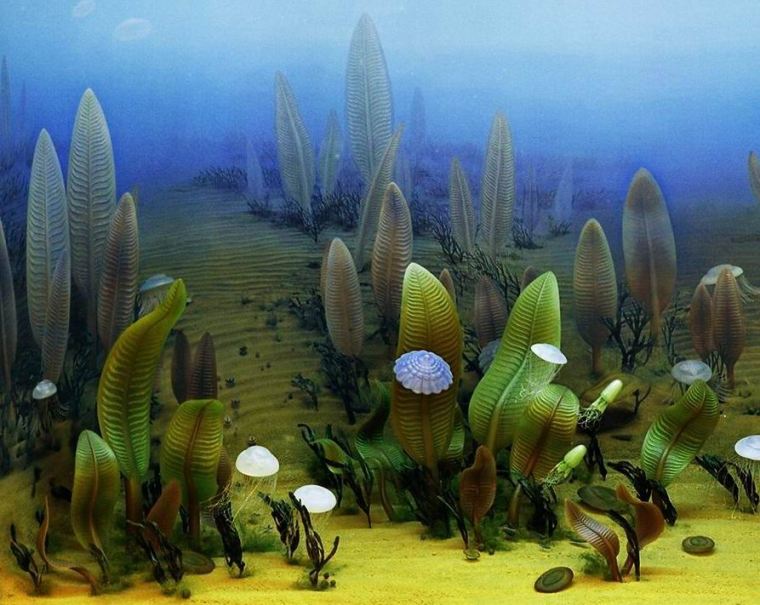

Above the S2 bed are carbonaceous cherts that contain carbon-isotope evidence of a boom in single-celled organisms with a metabolism that depended on iron and phosphorus rather than sunlight. The authors suggest that the tsunami triggered by impact would have stirred up soluble iron-2 from the deep ocean and washed in phosphorus from the exposed land surface, perhaps some having been delivered by the asteroid itself. No doubt such a huge impact would have veiled the Palaeoarchaean Earth with dust that reduced sunlight for years: inimical for photosynthesising bacteria but unlikely to pose a threat to chemo-autotrophs. An unusual feature of the S2 spherule bed is that it is capped by a layer of altered crystals whose shapes suggest they were originally sodium bicarbonate and calcium carbonate. They may represent flash-evaporation of up to tens of metres of ocean water as a result of the impact. Carbonates are less soluble than salt and more likely to crystallise during rapid evaporation of the ocean surface than would NaCl.

So it appears that early extraterrestrial bombardment in the early Archaean had the opposite effect to the Chicxulub impactor that devastated the highly evolved life of the late Mesozoic. Many repeats of such chaos during the Palaeoarchaean could well have given a major boost to some forms of early, chemo-autotrophic life, while destroying or setting back evolutionary attempts at photo-autotrophy.

See also: King, A. 2024. Meteorite 200 times larger than one that killed dinosaurs reset early life. Chemistry World 23 October 2024.