Chinese apothecary shops sell an assortment of fossils. They include shells of brachiopods that when ground up and dissolved in water allegedly treat rheumatism, skin diseases, and eye disorders. Traditional apothecaries also supply ‘dragons’ teeth’, said by Dr Subhuti Dharmananda, Director of the Institute for Traditional Medicine in Portland, Oregon to treat epilepsy, madness, manic running about, binding qi (‘vital spirit’) below the heart, inability to catch one’s breath, and various kinds of spasms, as well as making the body light, enabling one to communicate with the spirit light, and lengthening one’s life. Presumably have done a roaring trade in ‘dragons’ teeth’ since they were first mentioned in a Chinese pharmacopoeia (the Shennong Bencao Jing) from the First Century of the Common Era. In 1935 the anthropologist Gustav von Koenigswald came across two ‘dragons’ teeth’ in a Hong Kong shop. They were unusually large molars and he realised they were from a primate, but far bigger (20 × 22 mm) than any from living or fossil monkeys, apes or humans.

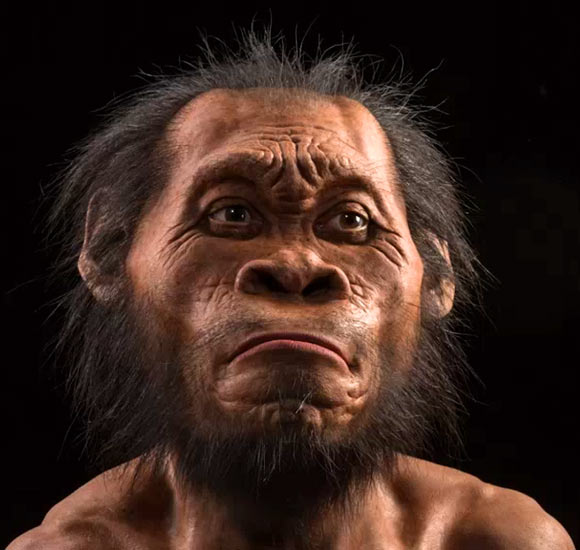

Eventually, in 1952 (he had been interned by Japanese forces occupying Java), von Koenigswald formally described the teeth and others that he had found. Their affinities and size prompted him to call the former bearer the ‘Huge Ape’ (Gigantopithecus). By 1956 Chinese palaeontologists had tracked down the cave site in Guangxi province where the teeth had been sourced, and a local farmer soon unearthed a complete lower jawbone (mandible) that was indeed gigantic. More teeth and mandibles have since been found at several sites in Southern and Southeast Asia, with an age range from about 2.0 to 0.3 Ma. Anatomical differences between teeth and mandibles suggest that there may have been 4 different species. Using mandibles as a very rough guide to overall size it has been estimated that Gigantopithecus may have been up to 3 m tall weighing almost 600kg.

Plaque on some teeth contain evidence for fruit, tubers and roots, but not grasses, which suggest suggest that Gigantopithecus had a vegetarian diet based on forest plants. Mandibles also showed affinities with living and fossil orangutans (pongines). Analysis of proteins preserved in tooth enamel confirm this relationship (Welker, F. and 17 others 2019. Enamel proteome shows that Gigantopithecus was an early diverging pongine. Nature, v.576, p. 262–265; DOI: 10.1038/s41586-019-1728-8). It was one of the few members of the southeast Asian megafauna to go extinct at the genus level during the Pleistocene. Its close relative Pongo the orangutan survives as three species in Borneo and Sumatra. Detailed analysis of material from 22 southern Chinese caves that have yielded Gigantopithecus teeth has helped resolve that enigma (Zhang, Y. and 20 others 2024. The demise of the giant ape Gigantopithecus blacki. Nature, v. 625; DOI: 10.1038/s41586-023-06900-0).

At the time Gigantopithecus first appeared in the geological record of China (~2.2 Ma), it ranged over much of south-western China. The early Pleistocene ecosystem there was one of diverse forests sufficiently productive to support large numbers of this enormous primate and also the much smaller orangutan Pongo weidenreichi. By 295 to 215 ka, the age of the last known Gigantopithecus fossils, its range had shrunk dramatically. The teeth show marked increases in size and complexity by this time, which suggests adaptation of diet to a changing ecosystem. That is confirmed by pollen analysis of cave sediments which reveal a dramatic decrease in forest cover and increases in fern and non-arboreal flora at the time of extinction. One physical sign of environmental stress suffered by individual late G. blacki is banding in their teeth defined by large fluctuations of barium and strontium concentrations relative to calcium. The bands suggest that each individual had to change its diet repeatedly over its lifetime. Closely related orangutans, on the other hand survived into the later Pleistocene of China, having adapted to the changed ecosystem, as did early humans in the area. It thus seems likely that Gigantopithecus was an extreme specialist as regards diet, and was unable to adapt to changes brought on by the climate becoming more seasonal. Today’s orangutans in Indonesia face a similar plight, but that is because they have become restricted to forest ‘islands’ in the midst of vast areas of oil palm plantations. Their original range seems to have been much the same as that of Gigantopithecus, i.e. across south-eastern Asia, but Pongo seems to have gone extinct outside of Indonesia (by 57 ka in China) during the last global cooling and when forest cover became drastically restricted.