White Sands National Park in New Mexico, USA is notorious for being adjacent to the site at which the first nuclear weapon was tested (code name Trinity) on 16 July 1945. Four weeks later two such bombs killed between 129,000 and 226,000 people at Hiroshima (6 August 1945) and Nagasaki (9 August 1945). The area is one of spectacular geology, the white sand being made of gypsum (CaSO4) grains precipitated from lake water supplied by rivers that had dissolved the mineral from Permian evaporites in the surrounding mountains. Subsequent wind erosion created a large, white dune field: the main attraction. Though a national park that has been proposed for UNESCO World Heritage Centre, the park itself is surrounded by military installations including the nuclear test site.

As in most evaporite basins, the White Sands’ gypsum sediments built up layer-by-layer through deposition of clays during successive inundations followed by evaporation of CaSO4 rich water. Animals crossing the basin were likely to leave trackways, which subsequent sedimentary cycles could preserve in stratigraphic order. Examples had been found in the early 20th century, revealing the former presence of the late-Pleistocene megafauna: Columbian mammoths, ground sloths, ancient camels, dire wolves, lions, and sabre-toothed cats. One set of dire wolf prints found in the 2010s contained seeds that yielded a radiocarbon age of 18 ka. More recently, 61 human footprint tracks turned up in layers that also displayed signs of megafauna crossing the lake flats, in one case showing convincing signs of hunters having followed a giant ground sloth (Bennett, M.R. 2021 and 13 others 2021. Evidence of humans in North America during the Last Glacial Maximum. Science, v. 373, p. 1528-1531; doi: 10.1126/science.abg7586). Interestingly, many of the human tracks seem to have been made by teenagers and children with only a few made by adults. Dating of seeds in the sediment layers – and in some footprints – yielded 23 to 21 ka radiocarbon ages. This evidence suggested human occupation of New Mexico long before those who left Clovis-style artifacts around 13 ka and others who preceded them. However, the seeds that were dated are those of an aquatic grass (Ruppia cirrhosa), which may have absorbed older carbon from groundwater permeating the evaporite sediments. Being robust, the seeds could also have been transported by wind back and forth from plants that lived before the animals and humans left their marks in the saline flats. Such is the importance of the White Sands fossil trackways that a team of US and British geologists, some of whom authored Bennett et al. 2021, have sought to refute doubts of their antiquity (Pigati, J.S. and 10 others 2023. Independent age estimates resolve the controversy of ancient human footprints at White Sands. Science, v. 382, p. 73-75; DOI: 10.1126/science.adh5007).

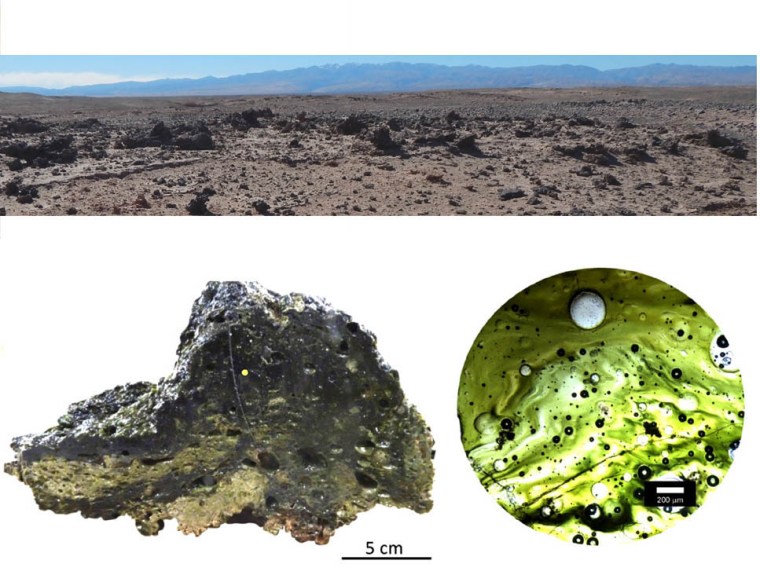

The researchers cut trenches into the layered clay-gypsum to reveal human footprints on three successive surfaces at the site where Ruppia seeds had provided very old, but disputed ages. They supplemented the earlier evidence by 14C dating of pollen grains blown into the prints from terrestrial plants and optically stimulated luminescence ages (time of last exposure to sunlight) of detrital quartz grains in the evaporites. The pollen dating gave ages from 23.4 to 22.6 ka, the minimum quartz OSL age being 21.5 ka. Similar ages from three different methods are pretty convincing evidence that humans were active in New Mexico during the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), and that absorption of older carbon from groundwater had not affected the Ruppia seeds.

The Asia to America migration, which led these hunters to what the abundant megafauna trackways suggest were rich pickings around the White Sands palaeo-lake, must have been earlier still. High-latitude North America was almost certainly a vast, frigid desert for thousands of years leading up to the LGM. Another implication of the remarkable finds in the gypsum beds is that migration most probably involved a coastal or even a maritime route along the Eastern Pacific shore to reach more habitable lower latitudes.

See also: Earliest Americans, and plenty of them. Earth-logs, 27July 2020; Prillaman, M. 2023. Human footprints in New Mexico really may be surprisingly ancient, new dating shows. Science News, 5 October 2023.