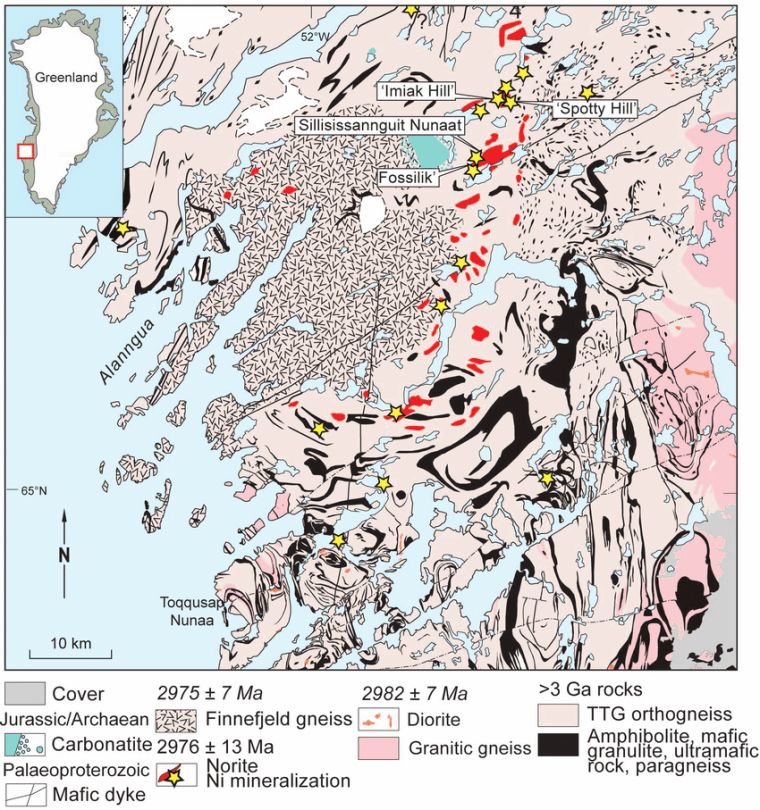

If ever there was one geological locality that ‘kept giving’ it would have to be the Isua supracrustal belt in West Greenland. Since 1971 it has been known to be the repository of the oldest known metasedimentary rocks, dated at around 3.7 Ga. Repeatedly, geochemists have sought evidence for life of that antiquity, but the Isua metasediments have yielded only ambiguous chemical signs. A more convincing hint emerged from iron-rich silica layers (jasper) in similarly aged metabasalts on Nuvvuagittuk Island in Quebec on the east side of Hudson Bay, Canada, which may be products of Eoarchaean sea-floor hydrothermal vents. X-ray micro-tomography and electron microscopy of the jaspers revealed twisted filaments, tubes, knob-like and branching structures up to a centimetre long that contain minute grains of carbon, phosphates and metal sufides, but the structures are made from hematite (Fe2O3) so an inorganic formation is just as likely as the earliest biology. Isua’s most intriguing contribution to the search for the earliest life has been what look like stromatolites in a marble layer (see: Signs of life in some of the oldest rocks; September 2016). Such structures formed in later times on shallow sea floors through the secretion of biofilms by photosynthesising blue-green bacteria.

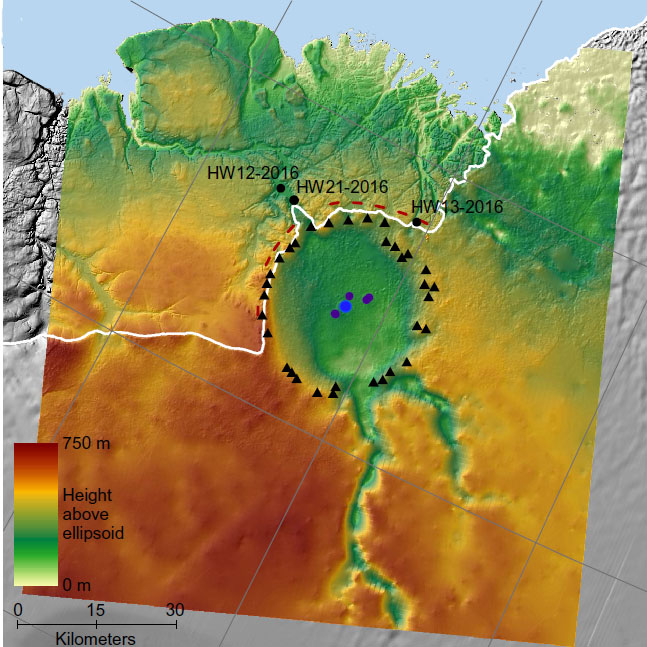

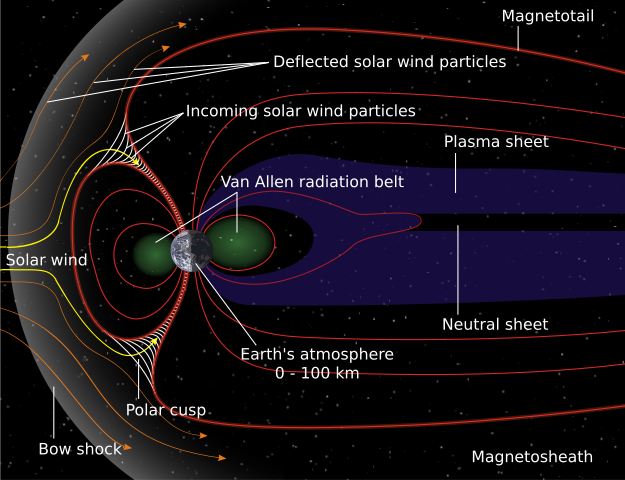

For life to form and survive depends on its complex molecules being protected from high-energy charged particles in the solar wind. In turn that depends on a strong geomagnetic field deflecting the solar wind as it does today, except for a small proportion that descend towards the poles and form aurora during solar mass ejections. In visits to Isua in 2018 and 2019, geophysicists from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, USA and Oxford University, UK drilled over 300 rock cores from metasedimentary ironstones (Nichols, C.I.O. and 9 others 2024. Possible Eoarchean records of the geomagnetic field preserved in the Isua Supracrustal Belt, southern West Greenland. Journal of Geophysics Research (Solid Earth), v. 129, article e2023JB027706; DOI: 10.1029/2023JB027706 Magnetisation preserved in the samples (remanent magnetism) suggest that it was formed by a geomagnetic field strength of at least 15 microtesla, similar to that which prevails today. The minerals magnetite (Fe3O4) and apatite (a complex phosphate) in the ironstones have been dated using U-Pb geochronometry and record a metamorphic event only slightly younger that the age of the Isua belt (3.69 and 3.63 Ga respectively). There is no sign of any younger heating above the temperatures that would reset the ironstones’ magnetisation. The Isua remanent magnetisation is at least 200 Ma older than that found in igneous rocks from north-eastern South Africa dated at between 3.2 to 3.45 Ga. So even in the Eoarchaean it seems likely that life, had it formed, would have avoided the hazard of exposure to the high energy solar wind. In all likelihood, however, in a shallow marine environment it would have had to protect itself somehow from intense ultraviolet radiation. That is now vastly reduced by stratospheric ozone (O3) which could only form once the atmosphere had appreciable oxygen (O2) content, i.e. after the Great Oxygenation Event beginning about 2.4 Ga ago. Undoubted stromatolites as old as 3.5 Ga suggest that early photosynthesising bacteria clearly had cracked the problem of UV protection somehow.