The idea of a ‘Hydrogen Economy’ has been around for at least six decades, its main attraction being that when hydrogen is burned it combines with oxygen to form H2O. It might seem to be the ultimate ‘green’ energy source, but it is currently being touted by governments and petroleum companies in what is widely regarded as ‘green washing’. The technology favoured by that axis uses steam reforming of the methane that dominates natural petroleum gas, through the reaction:

CH4 + H2O → CO + 3H2

It’s actually not much different from producing coke gas from coal, which began in the 19th century and is now largely abadoned. Because carbon monoxide (CO) reacts with atmospheric oxygen to form CO2 this process is by no means ‘green’ and is properly referred to as ‘grey’ hydrogen. Only if the CO is stored permanently underground could steam reforming not add to greenhouse warming. That puts the approach in the same category as ‘carbon capture and storage’, with all the possible difficulties inherent in that technology, which has yet to be demonstrated on a large scale. Such hydrogen is classified as a ‘blue’. Colour coding hydrogen is described nicely by the British National Grid. They give another six varieties. Green and yellow hydrogen are produced by electrolysing water using wind or solar power respectively. The pink variety uses nuclear power in the same fashion. Black or brown hydrogen is that produced by coking coal or stewing-up brown coal (lignite) which amazingly are contemplated in Australia and Germany. There is even a turquoise variety can be produced if methane is somehow turned into hydrogen and solid carbon using renewables. There is another category (white) which is hydrogen produced by a variety of natural, geochemical processes.

Earth-logs discussed white hydrogen in March 2023 when news emerged of gas that was 98% hydrogen leaking from a water borehole in Mali. The local people harnessed this surprising resource to generate electricity for their village. It also emerges in springs from ultramafic rocks, having formed through weathering of the mineral olivine:

3Fe2SiO4 + 2H2O → 2 Fe3O4 + 3SiO2 +3H2

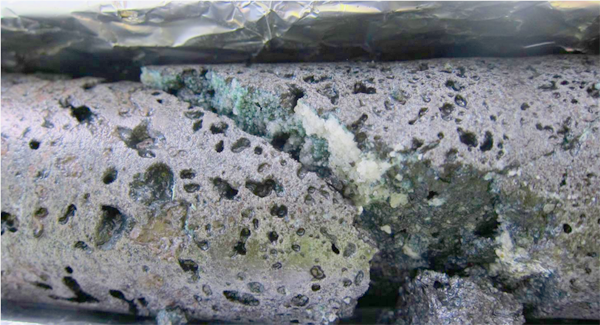

Much the same reaction occurs beneath the ocean floor where hydrothermal fluids alter basalts and in geothermal springs that emerge from onshore basalt lavas. Such ‘white’ hydrogen emissions are widespread. So an unknown, but possibly huge amount of hydrogen is leaking into the atmosphere continuously. Because of its tiny nucleus – just a single proton – atmospheric hydrogen quickly escapes to outer space: what a waste! Equally as interesting is that inducing the breakdown of ultramafic rock to yield hydrogen, by pumping water and carbon dioxide into them, may also be a means of leak-free carbon sequestration. This produces the complex mineral serpentine and magnesium carbonate. The reaction gives off heat and so is self sustaining until pumping is stopped.

It has been estimated that by 2050 the annual global demand for hydrogen will reach 530 million t. Just how big is the potential resource to meet such a demand? Natural weathering and hydrothermal processes have always functioned. Some of the hydrogen produced by them may have built-up in reservoirs like the one in Mali, some is escaping. Neither the magnitude of annual natural generation of hydrogen nor the amount trapped in porous sedimentary rocks are known in any detail. A recent survey of how much may be trapped gives a range from 103 to 1010 million metric tons (Ellis, G.S. & Gelman, S.E. 2024. Model predictions of global geologic hydrogen resources. Science Advances, v. 10, article eado0955; DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.ado0955), most probably 5.6 trillion t. If only a tenth of that is recoverable, replacing fossil-fuel energy with that from white hydrogen to achieve net-zero CO2 emissions would be sustainable for about 400 years. That magnitude of trapped hydrogen reserves well exceeds all proven reserves of natural gas.

This estimate assumes using only hydrogen that has been naturally produced and stored beneath the Earth’s surface. Basalts and ultramafic rocks exposed at the land surface as ophiolites – ancient oceanic crust thrust onto continental crust – are abundant on every continent. Inducing hydrogen-producing chemical reactions in them by pumping water and CO2 into them is little different from the technology being used in fracking. This potential resource is effectively limitless. Combined with renewable energy technology, a hydrogen economy has no conceivable need for fossil fuels, except as organic-chemistry feedstock. Such a scenario for stabilising climate is almost certainly feasible. It could use the capital, technology and skills currently deployed by the petroleum industry that is currently driving society and the Earth in the opposite direction. It is capable of drilling 10 km below the continental surface or the ocean floor, and even into the Earth’s mantle that is made of . . . ultramafic rock.

Best wishes for the festive season to all Earth-logs followers and visitors