During the Industrial Revolution not only did the emission of greenhouse gases by burning fossil fuels start to increase exponentially, but so too did the movement of rock and sediment to get at those fuels and other commodities demanded by industrial capital. In the 21st century about 57 billion tons of geological materials are deliberately moved each year. Global population followed the same trend, resulting in increasing expansion of agriculture to produce food. Stripped of its natural cover on every continent soil began to erode at exponential rates too. The magnitude of human intervention in natural geological cycles has become stupendous, soil erosion now shifting on a global scale about 75 billion tons of sediment, more than three times the estimated natural rate of surface erosion. Industrial capital together with society as a whole also creates and dumps rapidly growing amounts of solid waste of non-geological provenance. The Geological Society of America’s journal Geology recently published two research papers that document how capital is transforming the Earth.

One of the studies is based on sediment records in the catchment of a tributary of the upper Mississippi River. The area is surrounded by prairie given over mainly to wheat production since the mid 19th century. The deep soil of the once seemingly limitless grassland developed by the prairie ecosystem is ideal for cereal production. In the first third of the 20th century the area experienced a burst of erosion of the fertile soil that resulted from the replacement of the deep root systems of prairie grasses by shallow rooted wheat. The soil had formed from the glacial till deposited by the Laurentide ice sheet than blanketed North America as far south as New York and Chicago. Having moved debris across almost 2000 km of low ground, the till is dominated by clay- and silt-sized particles. Once exposed its sediments moved easily in the wind. Minnesota was badly affected by the ‘Dust Bowl’ conditions of the 1930s, to the extent that whole towns were buried by up to 4.5 metres of aeolian sediment. For the first time the magnitude of soil erosion compared with natural rates has been assessed precisely by dating layers of alluvium deposited in river terraces of one of the Mississippi’s tributaries (Penprase, S.B. et al. 2025. Plow versus Ice Age: Erosion rate variability from glacial–interglacial climate change is an order of magnitude lower than agricultural erosion in the Upper Mississippi River Valley, USA. Geology, v. 53, p. 535-539; DOI: 10.1130/G52585.1).

Shanti Penprase of the University of Minnesota and her colleagues were able to date the last time sediment layers at different depths in terraces were exposed to sunlight and cosmic rays, by analysing optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) and cosmogenic 10Be content of quartz grains from the alluvium. The data span the period since the Last Glacial Maximum 20 thousand years ago during which the ecosystem evolved from bare tundra through re-vegetation to pre-settlement prairie. They show that post-glacial natural erosion had proceeded at around 0.05 mm yr-1 from a maximum of 0.07 when the Laurentide Ice Sheet was at its maximum extent. Other studies have revealed that after the area was largely given over to cereal production in the 19th century erosion rates leapt to as high as 3.5 mm yr-1 with a median rate of 0.6 mm yr-1, 10 to 12 times that of post-glacial times. It was the plough and single-crop farming introduced by non-indigenous settlers that accelerated erosion. Surprisingly, advances in prairie agriculture since the Dust Bowl have not resulted in any decrease in soil erosion rates, although wind erosion is now insignificant. The US Department of Agriculture considers the loss of one millimetre per year to be ‘tolerable’: 14 times higher than the highest natural rate in glacial times.

The other paper has a different focus: how human activities may form solid rock. The world over, a convenient means of disposing of unwanted material in coastal areas is simply to dump waste in the sea. That has been happening for centuries, but as for all other forms of anthropogenic waste disposal the volumes have increased at an exponential rate. The coast of County Durham in Britain began to experience marine waste disposal when deep mines were driven into Carboniferous Coal Measures hidden by the barren Permian strata that rest unconformably upon them. Many mines extended eastwards beneath the North Sea, so it was convenient to dump 1.5 million tons of waste rock annually at the seaside. The 1971 gangster film Get Carter starring Michael Caine includes a sequence showing ‘spoil’ pouring onto the beach below Blackhall colliery, burying the corpse of Carter’s rival. The nightmarish, 20 km stretch of grossly polluted beach between Sunderland and Hartlepool also provided a backdrop for Alien 3. Historically, tidal and wave action concentrated the low-density coal in the waste at the high-water mark, to create a free resource for locals in the form of ‘sea coal’ as portrayed in Tom Scott Robson’s 1966 documentary Low Water. Closure of the entire Duham coalfield in the 1980s and ‘90s halted this pollution and the coast is somewhat restored – at a coast of around £10 million.

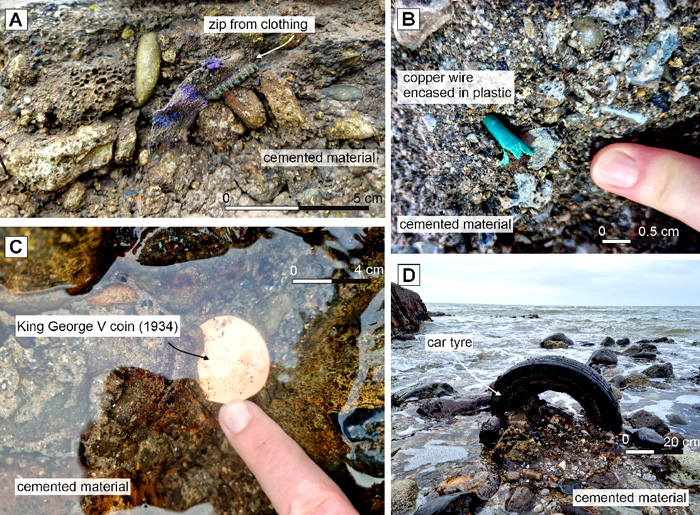

On the West Cumbrian coast of Britain another industry dumped millions of tons of waste into the sea. In the case it was semi-molten ‘slag’ from iron-smelting blast furnaces poured continuously for 130 years until steel-making ended in the 1980s. Coastal erosion has broken up and spread an estimated 27 million cubic metres of slag along a 2 km stretch of beach. Astonishingly this debris has turned into a stratum of anthropogenic conglomerate sufficiently well-bonded to resist storms (Owen, A., MacDonald, J.M. & Brown, D.J 2025. Evidence for a rapid anthropoclastic rock cycle. Geology, v. 53, p. 581–586; DOI: 10.1130/G52895.1). The conglomerate is said by the authors to be a product of ‘anthropoclastic’ processes. Its cementation involves minerals such as goethite, calcite and brucite. Because the conglomerate contains car tyres, metal trouser zips, aluminium ring-pulls from beer cans and even coins lithification has been extremely rapid. One ring-pull has a design that was not used in cans until 1989, so lithification continued in the last 35 years.

Furnace slag ‘floats’ on top of smelted iron and incorporates quartz, clays and other mineral grains in iron ore into anhydrous calcium- and magnesium-rich aluminosilicates. This purification is achieved deliberately by including limestone as a fluxing agent in the furnace feed. The high temperature reactions are similar to those that produce aluminosilicates when cement is manufactured. Like them, slag breaks down in the presence of water to recrystallis in hydrated form to bond the conglomerate. This is much the same manner as concrete ‘sets’ over a few days and weeks to bind together aggregate. There is vastly more ‘anthropoclastic’ rock in concrete buildings and other modern infrastructure. Another example is tarmac that coats millions of kilometres of highway.

See also: Howell, E. 2025. Modern farming has carved away earth faster than during the ice age. Science, v. 388