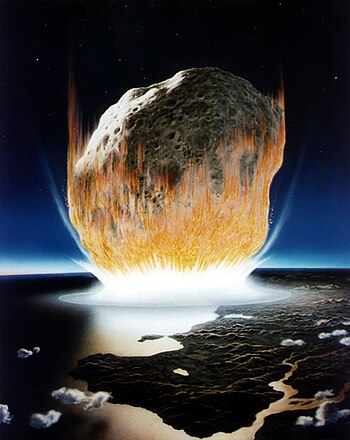

One of the most eagerly followed ocean-floor drilling projects has just released some results. Its target is 46 km radially away from the centre of the geophysical anomaly associated with the Chixculub impact structure just to the north of Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula. In the case of large lunar impact craters the centre is often surrounded by a ring of peaks. Modelling suggests such features are produced by the deep penetration of immense seismic shock waves. In the first minute these excavate and fling out debris to leave a cavity penetrating deep into the crust. Within three minutes the cavity walls collapse inwards creating a rebound superficially similar to the drop flung upwards after an object is dropped in liquid. This, in turn, collapses outwards to emplace smashed and partially melted deep crustal material on top of what were once surface materials, creating a crustal inversion beneath a mountainous ring of Himalayan dimensions that surrounds a by-now shallow crater. That is the story modelled from what is known about well-studied, big craters on the Moon and Mercury. Chixculub is different because the impact was into the sea and involved debris-charged tsunamis that finally plastered the actual impact scar with sediments. The drilling was funded for several reasons, some palaeontological others relating to the testing of theories of impact processes and their products. Chixculub is probably the only intact impact crater on Earth, and the first reports of findings are in the second category (Morgan, J.V. and 37 others 2016. The formation of peak rings in large impact craters. Science, v. 354, p. 878-882; doi: 10.1126/science.aah6561).

The drill core, reaching down to about 1.3 km below the sea floor penetrates post-impact Cenozoic sediments into a 100 m thick zone of breccias containing fragments of impact melt rock, probably the infill of the central crater immediately following the first few minutes of impact. Beneath that are coarse grained granites representing the middle continental crust from original depths around 10 km. The granite is intensely fractured and riven by dykes and pods of impact melt, and contains intensely shocked grains that typify impacts that produce a transient pressure of ~60 GPa – around six hundred thousand times atmospheric pressure. From seismic reflection surveys this crustal material overlies as yet un-drilled Mesozoic sedimentary rocks. Its density is significantly less than that of unshocked granite – averaging 2.4 compared with 2.6 g cm3. So it is probably filled with microfractures and sufficiently permeable for water to have penetrated once the impact site had cooled. This poses the question, yet to be addressed in print, of whether or not this near-surface layer became colonised by microorganisms in the aftermath (Barton, P. 2016. Revealing the dynamics of a large impact. Science, v. 354, p. 836-837). That is, was the surrounding ocean sterilised at the time of the K-T (K-Pg) mass extinction?; an issue whose resolution is awaited with bated breath by the palaeobiology audience. OK; so theory about the physical process of cratering has been validated to some extent, but will later results be more interesting, outside the planetary sciences community?

Read more about impacts here and mass extinctions here .