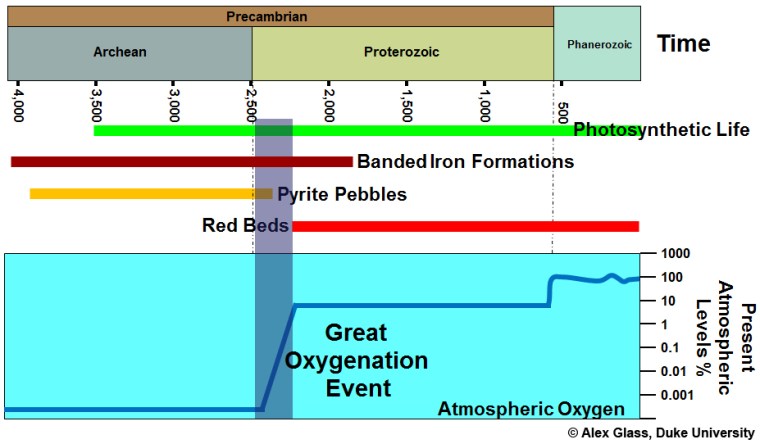

For life on Earth, one of the most fundamental shifts in ecosystems was the Great Oxygenation Event 2.5 to 2.3 billion years (Ga) ago. The first evidence for its occurrence was from the sedimentary record, particularly ancient soils (palaeosols) that mark exposure of the continental surface above sea level and rock weathering. Palaeosols older than 2.4 Ga have low iron contents that suggest iron was soluble in surface waters, i.e. in its reduced bivalent form Fe2+. Sediments formed by flowing water also contain rounded grains of minerals that in today’s oxygen-rich environments are soon broken down and dissolved through oxidising reactions, for instance pyrite (FeS2) and uraninite (UO2). After 2.4 Ga palaeosols are reddish to yellowish brown in colour and contain insoluble oxides and hydroxides of Fe3+ principally hematite (Fe2O3) and goethite (FeO.OH). After this time sediments deposited by wind action and rivers are similar in colour: so-called ‘redbeds’. Following the GOE the atmosphere initially contained only traces of free oxygen, but sufficient to make the surface environment oxidising. In fact such an atmosphere defies Le Chatelier’s Principle: free oxygen should react rapidly with the rest of the environment through oxidation. That it doesn’t shows that it is continually generated as a result of oxygenic photosynthesis. The CO2 + H2O = carbohydrate + oxygen equilibrium does not reach a balance because of continual burial of dead organic material.

Free oxygen is a prerequisite for all multicelled eukaryotes, and it is probably no coincidence that fossils of the earliest known ones occur in sediments in Gabon dated at 2.1 Ga: 300 Ma after the Great Oxygenation Event. However, the GOE relates to surface environments of that time. From 2.8 Ga – in the Mesoarchaean Era – to the late Palaeoproterozoic around 1.9 Ga, vast quantities of Fe3+ were locked in iron oxide-rich banded iron formations (BIFs): roughly 105 billion tons in the richest deposits alone (see: Banded iron formations (BIFs) reviewed; December 2017). Indeed, similar ironstones occur in Archaean sedimentary sequences as far back as 3.7 Ga, albeit in uneconomic amounts. Paradoxically, enormous amounts of oxygen must have been generated by marine photosynthesis to oxidise Fe2+ dissolved in the early oceans by hydrothermal alteration of basalt lava upwelling from the Archaean mantle. But none of that free oxygen made it into the atmosphere. Almost as soon as it was released it oxidised dissolved Fe2+ to be dumped as iron oxide on the ocean floor. Before the GOE that aspect of geochemistry did obey Le Chatelier!

The only likely means of generating oxygen on such a gargantuan scale from the earliest Archaean onwards is through teeming prokaryote organisms capable of oxygenic photosynthesis. Because modern cyanobacteria do that, the burden of the BIFs has fallen on them. One reason for that hypothesis stems from cyanobacteria in a variety of modern environments building dome-shaped bacterial mats. Their forms closely resemble those of Archaean stromatolites found as far back as 3.7 Ga. But these are merely peculiar carbonate bodies that could have been produced by bacterial mats which deploy a wide variety of metabolic chemistry. Laureline Patry of the Université de Bretagne Occidentale, Plouzané, France, and colleagues from France, the US, Canada and the UK have developed a novel way of addressing the opaque mechanism of Archaean oxygen production (Patry, L.A. and 12 others. Dating the evolution of oxygenic photosynthesis using La-Ce geochronology. Nature, v. 642, p. 99-104; DOI: 10.1038/s41586-025-09009-8).

They turned to the basic geochemistry of rare earth elements (REE) in Archaean stromatolitic limestones from the Superior Craton of northern Canada. Of the 17 REEs only cerium (Ce) is capable of being oxidised in the presence of oxygen. As a result Ce can be depleted relative to its neighbouring REEs in the Periodic Table, as it is in many Phanerozoic limestones. Five samples of the limestones show consistent depletion of Ce relative to all other REE. It is also possible to date when such fractionation occurred using 138La– 138Ce geochronology. The samples were dated at 2.87 to 2.78 Ga (Mesoarchaean), making them the oldest limestones that show Ce anomalies and thus oxygenated seawater in which the microbial mats thrived. But that is only 300 Ma earlier than the start of the GOE. Stromatolites are abundant in the Archaean record as far back as 3.4 Ga, so it should be possible to chart the link between microbial carbonate mats and oxygenated seawater to a billion years before the GOE, although that does not tell us about the kind of microbes that were making stromatolites.

See also: Tracing oxygenic photosynthesis via La-Ce geochronology. Bioengineer.org, 29 May 2025; Allen, J.F. 2016. A proposal for formation of Archaean stromatolites before the advent of oxygenic photosynthesis. Frontiers in Microbiology, v. 7; DOI: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01784.