A symposium hosted by the Royal Society in 1965 aimed at resurrecting Alfred Wegener’s hypothesis of continental drift. During the half century since Wegener made his proposal in 1915, it had been studiously ignored by most geologists. The majority had bumbled along with the fixist ideology of their Victorian predecessors. The symposium launched what can only be regarded as a revolution in the Earth Sciences. In the three years following the symposium, the basic elements of plate tectonics had emerged from a flurry of papers, mainly centred on geophysical evidence. Geology itself became part of this cause célèbre through young scientists eager to make a name for themselves. The geological history of Britain, together with that of the eastern North America, became beneficiaries only four years after the Royal Society meeting (Dewey, J. 1969. Evolution of the Appalachian/Caledonian Orogen. Nature 222, 124–129; DOI: 10.1038/222124a0).

In Britain John Dewey, like a few other geologists, saw plate theory as key to understanding the many peculiarities revealed by geological structure, igneous activity and stratigraphy of the early Palaeozoic. These included very different Cambrian and Ordovician fossil assemblages in Scotland and Wales, now only a few hundred kilometres apart. The Cambro-Ordovician of NW Scotland was bounded to the SE by a belt of highly deformed and metamorphosed Proterozoic to Ordovician sediments and volcanics forming the Scottish Highlands. That was terminated to the SE by a gigantic fault zone containing slivers of possible oceanic lithosphere. The contorted and ‘shuffled’ Ordovician and Silurian sediments of the Southern Uplands of Scotland. The oldest strata seemed to have ocean-floor affinities, being deposited on another sliver of ophiolites. A few tens of km south of that there was a very different Lower Palaeozoic stratigraphy in the Lake District of northern England. It included volcanic rocks with affinities to those of modern island arcs. A gap covered by only mildly deformed later Palaeozoic shelf and terrestrial sediments, dotted by inliers of Proterozoic sediments and volcanics separated the Lake District from yet another Lower Palaeozoic assembly of arc volcanics and marine sediments in Wales. Intervening in Anglesey was another Proterozoic block of deformed sediments that also included ophiolites.

Dewey’s tectonic assessment from this geological hodge-podge, which had made Britain irresistible to geologists through the 19th and early 20th centuries, was that it had resulted from blocks of crust (terranes), once separated by thousands of kilometres, being driven into each other. Britain was thus formed by the evolution and eventual destruction of an early Palaeozoic ocean, Iapetus: a product of plate tectonics. Scotland had a fundamentally different history from England and Wales; the unification of several terranes having taken over 150 Ma of diverse tectonic processes. Dewey concluded that the line of final convergence lay at a now dead, major subduction zone – the Iapetus Suture – roughly beneath the Solway Firth. During the 56 years since Dewey’s seminal paper on the Caledonian-Appalachian Orogeny details and modifications have been added at a rate of around one to two publications per year. The latest seeks to date when and where the accretion of 6 or 7 terranes was finally completed (Waldron, J.W.F. et al. 2025. Is Britain divided by an Acadian suture? Geology, v. 53, p. 847–852; DOI: 10.1130/G53431.1).

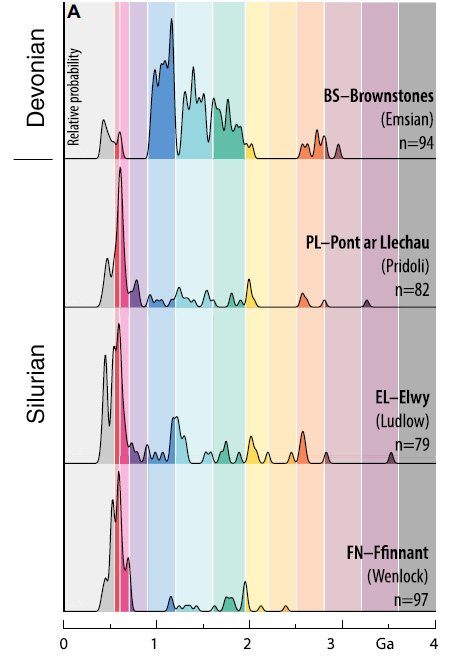

John Waldron and colleagues from the University of Alberta and Acadia University in Canada and the British Geological Survey addressed this issue by extracting zircons from four late Silurian and early Devonian sandstones in North and South Wales. These sediments had been deposited between 433 and 393 Ma ago at the southernmost edge of the British Caledonide terrane assemblage towards the end of terrane assembly. The team dated roughly 250 zircons from each sandstone using the 207Pb/206Pb and 206Pb/238U methods. Each produced a range of ages, presumed to be those of igneous rocks from whose magma the zircon grains had crystallised. These data are expressed as plots of probable frequency against age. Each pattern of ages is assumed to be a ‘fingerprint’ for the continental crust from which the zircons were eroded and transported to their resting place in their host sediment. In this case, the researchers were hoping to see signs of continental crust from the other side of the Caledonian orogen; i.e. from the Precambrian basement of the Laurentia continent.

The three late-Silurian sediments showed distinct zircon-age peaks around 600 Ma and a spread of smaller peaks extending to 2.2 Ga. This tallied with a sediment source in Africa, from which the southernmost Caledonian terrane was said to have split and moved northwards. The Devonian sediment lacked signs of such an African ‘heritage’ but had a prominent age peak at about 1.0 Ga, absent from the Welsh Silurian sediments. Not only is this a sign of different sediment provenance but closely follows the known age of a widespread magmatic pulse in the Laurentian continent. So, sediment transport from the opposite side of the Iapetus Ocean across the entire Caledonian orogenic belt was only possible after the end of the Silurian Period at around 410 Ma. There must have been an intervening barrier to sediment movement from Laurentia before that, such as deep ocean water further north. Previous studies from more northern Caledonian terranes show that Laurentian zircons arrived in the Southern Uplands of Scotland and the English Lake District around 432 Ma in the mid-Silurian. Waldron et al. suggest, on these grounds that the suture marking the final closure of the Iapetus Ocean lies between the English Lake District and Anglesey, rather than beneath the Solway. They hint that the late-Silurian to early Devonian granite magmatism that permeated the northern parts of the Caledonian-Appalachian orogen formed above northward subduction of the last relics of Iapetus, which presaged widespread crustal thickening known as the Acadian orogeny in North America.

Readers interested in this episode of Earth history should download Waldron et al.’s paper for its excellent graphics, which cannot be reproduced adequately here.