The International Commission on Stratigraphy (ICS) issues guidance for the division of geological history that has evolved from the science’s original approach: that was based solely on what could be seen in the field. That included: variations in lithology and the law of superposition; unconformities that mark interruptions through deformation, erosion and renewed deposition; the fossil content of sediments and the law of faunal succession; and more modern means of division, such as geomagnetic changes detected in rock over time. That ‘traditional’ approach to relative time is now termed chronostratigraphy, which has evolved since the 19th century from the local to the global scale as geological research widened its approach. Subsequent development of various kinds of dating has made it possible to suggest the actual, absolute time in the past when various stratigraphic boundaries formed – geochronology. Understandably, both are limited by the incompleteness of the geological record – and the whims of individual geologists. For decades the ICS has been developing a combination of both approaches that directly correlates stratigraphic units and boundaries with accurate geochronological ages. This is revised periodically, the ICS having a detailed protocol for making changes. You can view the Cenozoic section of the latest version of the International Chronostratigraphic Chart and the two systems of units below. If you are prepared to travel to a lot of very remote places you can see a monument – in some cases an actual Golden Spike – marking the agreed stratigraphic boundary at the ICS-designated type section for 80 of the 93 lower boundaries of every Stage/Age in the Phanerozoic Eon. Each is a sonorously named Global Boundary Stratotype Section and Point or GSSP (see: The Time Lords of Geology, April 2013). There are delegates to various subcommissions and working groups of the ICS from every continent, they are very busy and subject to a mass of regulations …

On 11 May 2011, the Geological Society of London hosted a conference, co-sponsored by the British Geological Survey, to discuss evidence for the dawn of a new geological Epoch: the Anthropocene, supposedly marking the impact of humans on Earth processes. There has been ‘lively debate’ about whether or not such a designation should be adopted. An Epoch is at the 4th tier of the chronostratigraphic/geochronologic systems of division, such as the Holocene, Pleistocene, Pliocene and Miocene, let alone a whole host of such entities throughout the Phanerozoic, all of which represent many orders of magnitude longer spans of time and a vast range of geological events. No currently agreed Epoch lasted less than 11.7 thousand years (the Holocene) and all the others spanned 1 Ma to tens of Ma (averaged at 14.2 Ma). Indeed, even geological Ages (the 5th tier) span a range from hundreds of thousands to millions of years (averaged at 6 Ma). Use ‘Anthropocene’ in Search Earth-logs to read posts that I have written on this proposal since 2011, which outline the various arguments for and against it.

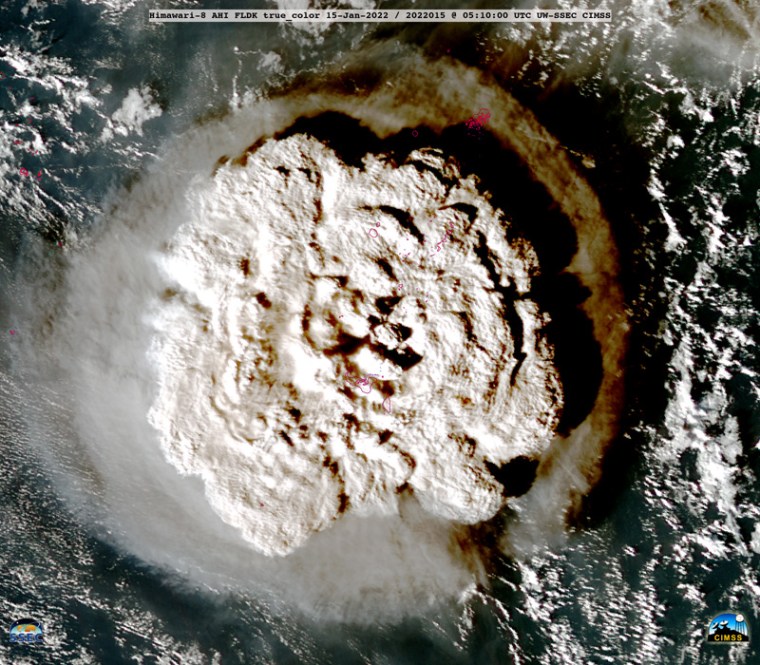

In the third week of May 2019 the 34-member Anthropocene Working Group (AWG) of the ICS convened to decide on when the Anthropocene actually started. The year 1952 was proposed – the date when long-lived radioactive plutonium first appears in sediments before the 1962 International Nuclear Test-Ban Treaty. Incidentally, the AWG proposed a GSSP for the base of the Anthropocene in a sediment core through sediments in the bed of Crawford Lake an hour’s drive west of Toronto, Canada. After 1952 there are also clear signs that plastics, aluminium, artificial fertilisers, concrete and lead from petrol began to increase in sediments. The AWG accepted this start date (the Anthropocene ‘golden spike’) by a 29 to 5 vote, and passed it into the vertical ICS chain of decision making. This procedure reached a climax on Monday 4 March 2024, at a meeting of the international Subcommission on Quaternary Stratigraphy (SQS): part of the ICS. After a month-long voting period, the SQS announced a 12 to 4 decision to reject the proposal to formally declare the Anthropocene as a new Epoch. Normally, there can be no appeals for a losing vote taken at this level, although a similar proposal may be resubmitted for consideration after a 10 year ‘cooling off’ period. Despite the decisive vote, however, the chair of the SQS, palaeontologist Jan Zalasiewicz of the University of Leicester, UK, and one of the group’s vice-chairs, stratigrapher Martin Head of Brock University, Canada have called for it to be annulled, alleging procedural irregularities with the lengthy voting procedure.

Had the vote gone the other way, it would marked the end of the Holocene, the Epoch when humans moved from foraging to the spread of agriculture, then the ages of metals and ultimately civilisation and written history. Even the Quaternary Period seemed under threat: the 2.5 Ma through which the genus Homo emerged from the hominin line and evolvd. Yet a pro-Anthropocene vote would have faced two more, perhaps even more difficult hurdles: a ratification vote by the full ICS, and a final one in August 2024 at a forum of the International Union of Geological Sciences (IUGS), the overarching body that represents all aspects of geology.

There can be little doubt that the variety and growth of human interferences in the natural world since the Industrial Revolution poses frightening threats to civilisation and economy. But what they constitute is really a cultural or anthropological issue, rather than one suited to geological debate. The term Anthropocene has become a matter of propaganda for all manner of environmental groups, with which I personally have no problem. My guess is that there will be a compromise. There seems no harm either way in designating the Anthropocene informally as a geological Event. It would be in suitably awesome company with the Permian and Cretaceous mass extinctions, the Great Oxygenation Event at the start of the Proterozoic, the Snowball Earth events and the Palaeocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum. And it would require neither special pleading nor annoying the majority of geologists. But I believe it needs another name. The assault on the outer Earth has not been inflicted by the vast majority of humans, but by a tiny minority who wield power for profit and relentless growth in production. The ‘Plutocracene’ might be more fitting. Other suggestions are welcome …

See also: Witze, A. 2024. Geologists reject the Anthropocene as Earth’s new epoch — after 15 years of debate. Nature, v. 627, News article; DOI: 10.1038/d41586-024-00675-8; Voosen, P. 2024. The Anthropocene is dead. Long live the Anthropocene. Science, v. 383, News article, 5 March 2024.