During the Pliocene (5.3 to 2.7 Ma) there evolved a network of various hominins, with their remains scattered across both the northern and southern parts of that continent. The earliest, though somewhat disputed hominin fossil Sahelanthropus tchadensis hails from northern Chad and lived around 7 Ma ago, during the late Miocene, as did a similarly disputed creature from Kenya Orrorin tugenensis (~5.8 Ma). The two were geographically separated by 1500 km, what is now the Sahara desert and the East African Rift System. The suggestion from mtDNA evidence that humans and chimpanzees had a common ancestor, the uncertainty about when it lived (between 13 to 5 Ma) and what it may have looked like, let alone where it lived, makes the notion debateable. There is even a possibility that the common ancestor of humans and the other anthropoid apes may have been European. Its descendants could well have crossed to North Africa when the Mediterranean Sea had been evaporated away to form the thick salt deposits that now lie beneath it: what could be termed the ‘Into Africa’ hypothesis. The better known Pliocene hominins were also widely distributed in the east and south of the African continent. Wandering around was clearly a hominin predilection from their outset. The same can be said about humans in the general sense (genus Homo) during the Early Pleistocene when some of them left Africa for Eurasia. Artifacts dated at 2.1 Ma have been found on the Loess Plateau of western China, and Georgia hosts the earliest human remains known from Eurasia. Since them H. antecessor, heidelbergensis, Neanderthals and Denisovans roamed Eurasia. Then, after about 130 ka, anatomically modern humans progressively populated all continents, except Antarctica, to their geographic extremities and from sea level to 4 km above it.

There is a popular view that curiosity and exploration are endemic and perhaps unique to the human line: ‘It’s in our genes’. But even plants migrate, as do all animal species. So it is best to be wary of a kind of hominin exceptionalism or superior motive force. Before settled agriculture, simply diffusion of populations in search of sustenance could have achieved the enormous migrations undertaken by all hominins: biological resources move and hunter gatherers follow them. The first migration of Homo erectus from Africa to northern China by way of Georgia seems to taken 200 ka at most and covered about ten thousand kilometres: on average a speed of only 50 m per year! That achievement and many others before and later were interwoven with the evolution of brain size, cognitive ability, means of communication and culture. But what were the ultimate drivers? Two recent papers in the journal Nature Communications make empirically-based cases for natural forces driving the movement of people and changes in demography.

The first considers hominin dispersal in the Palaearctic biogeographic realm: the largest of eight originally proposed by Alfred Russel Wallace in the late 19th century that encompasses the whole of Eurasia and North Africa (Zan, J. et al. 2024. Mid-Pleistocene aridity and landscape shifts promoted Palearctic hominin dispersals. Nature Communications, v. 15, article 10279; DOI: 10.1038/s41467-024-54767-0). The Palearctic comprises a wide range of ecosystems: arid to wet, tropical to arctic. After 2 Ma ago, hominins moved to all its parts several times. The approach followed by Zan et al. is to assess the 3.6 Ma record of the thick deposits of dust carried by the perpetual westerly winds that cross Central Asia. This gave rise to the huge (635,000 km2) Loess Plateau. At least 17 separate soil layers in the loess have yielded artefacts during the last 2.1 Ma. The authors radiocarbon dated the successive layers of loess in Tajikistan (286 samples) and the Tarim Basin (244 samples) as precisely as possible, achieving time resolutions of 5 to 10 ka and 10 to 20 ka respectively. To judge variations in climate in these area they also measured the carbon isotopic proportions in organic materials preserved within the layers. Another climate-linked metric that Zan et al. is a time series showing the development of river terraces across Eurasia derived from the earlier work of many geomorphologists. The results from those studies are linked to variations through time in the numbers of archaeological sites across Eurasia that have yielded hominin fossils, stone tools and signs of tool manufacture, many of which have been dated accurately.

The authors use sophisticated statistics to find correlations between times of climatic change and the signs of hominin occupation. Episodes of desertification in Palaearctic Eurasia clearly hindered hominins’ spreading across the continent either from west to east of vice versa. But there were distinct, periodic windows of climatic opportunity for that to happen that coincide with interglacial episodes, whose frequency changed at the Mid Pleistocene Transition (MPT) from about 41 ka to roughly every 100 ka. That was suggested in 2021 to have arisen from an increased roughness of the rock surface over which the great ice sheets of the Northern Hemisphere moved. This suppressed the pace of ice movement so that the 41 ka changes in the tilt of the Earth’s rotational axis could no longer drive climate change during the later Pleistocene, despite the fact that the same astronomical influence continued. The succeeding ~100 ka pulsation may or may not have been paced by the very much weaker influence of Earth changing orbital eccentricity. Whichever, after the MPT climate changes became much more extreme, making human dispersal in the Palearctic realm more problematic. Rather than hominin’s evolution driving them to a ‘Manifest Destiny’ of dominating the world vastly larger and wider inorganic forces corralled and released them so that, eventually, they did.

Much the same conclusion, it seems to me, emerges from a second study that covers the period since ~ 9 ka ago when anatomically modern humans transitioned from a globally dominant hunter-gatherer culture to one of ‘managing’ and dominating ecosystems, physical resources and ultimately the planet itself. (Wirtz, K.W et al. 2024. Multicentennial cycles in continental demography synchronous with solar activity and climate stability. Nature Communications, v. 15, article 10248; DOI: 10.1038/s41467-024-54474-w). Like Zan et al., Kai Wirtz and colleagues from Germany, Ukraine and Ireland base their findings on a vast accumulated number (~180,000) of radiocarbon dates from Holocene archaeological sites from all inhabited continents. The greatest number (>90,000) are from Europe. The authors applied statistical methods to judge human population variations since 11.7 ka in each continental area. Known sites are probably significantly outweighed by signs of human presence that remain hidden, and the diligence of surveys varies from country to country and continent to continent: Britain, the Netherlands and Southern Scandinavia are by far the best surveyed. Given those caveats, clearly this approach gives only a blurred estimate of population dynamics during the Holocene. Nonetheless the data are very interesting.

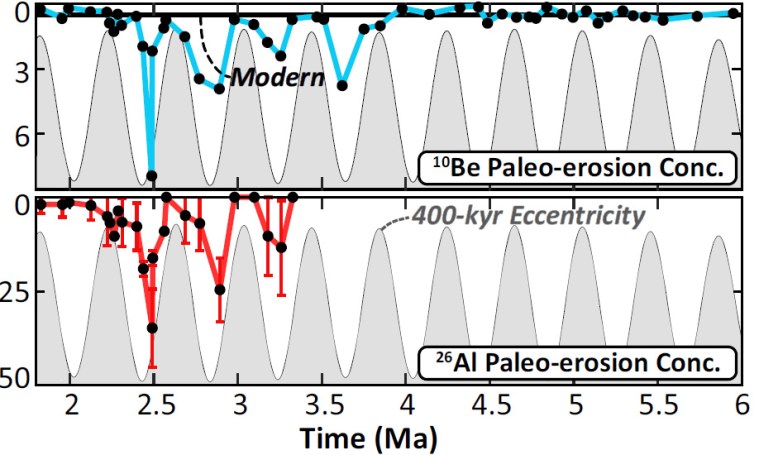

The changes in population growth rates show distinct cyclicity during the Holocene, which Wirtz et al. suggest are signs of booms and busts in population on all six continents. Matching these records against a large number of climatic time series reveals a correlation. Their chosen metric is variation in solar irradiance: the power per unit area received from the Sun. That has been directly monitored only over a couple of centuries. But ice cores and tree rings contain proxies for solar irradiance in the proportions of the radioactive isotopes 10Be and 14C contained in them respectively. Both are produced by the solar wind of high-energy charged particles (electrons, protons and helium nuclei or alpha particles) penetrating the upper atmosphere. The two isotopes have half-lives long enough for them to remain undecayed and thus detectable for tens of thousand years. Both ice cores and tree rings have decadal to annual time resolutions. Wirtz et al. find that their crude estimates of booms and busts in human populations during the Holocene seem closely to match variations in solar activity measured in this way. Climate stability favours successful subsistence and thus growth in populations. Variable climatic conditions seem to induce subsistence failures and increase mortality, probably through malnutrition.

A nice dialectic clearly emerges from these studies. ‘Boom and bust’ as regards populations in millennial and centennial to decadal terms stem from climate variations. Such cyclical change thus repeatedly hones natural selection among the survivors, both genetically and culturally, increasing their general fitness to their surroundings. Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels would have devoured these data avidly had they emerged in the 19th century. I’m sure they would have suggested from the evidence that something could go badly wrong – negation of negation, if readers care to explore that dialectical law further . . . And indeed that is happening. Humans made ecologically very fit indeed in surviving natural pressures are now stoking up a major climatic hiccup, or rather the culture and institutions that humans have evolved are doing that.