Carbon capture and storage is in the news most weeks and is increasingly on the agenda for some governments. But plans to implement the CCS approach to reducing and stopping global warming increasingly draws scorn from scientists and environmental campaigners. There is a simple reason for their suspicion. State engagement, in the UK and other rich countries, involves major petroleum companies that developed the oil and gas fields responsible for unsustainably massive injection of CO2 into the atmosphere. Because they have ‘trousered’ stupendous profits they are a tempting source for the financial costs of pumping CO2 into porous sedimentary rocks that once contained hydrocarbon reserves. Not only that, they have conducted such sequestration over decades to drive out whatever petroleum fluids remaining in previously tapped sedimentary strata. For that second reason, many oil companies are eager and willing to comply with governmental plans, thereby seeming to be environmentally ‘friendly’. It also tallies with their ambitions to continue making profits from fossil-fuel extraction. But isn’t that simply a means of replacing the sequestered greenhouse gas with more of it generated by burning the recovered oil and natural gas; i.e. ‘kicking the can down the road’? Being a gas – technically a ‘free phase’ – buried CO2 also risks leaking back to the atmosphere through fractures in the reservoir rock. Indeed, some potential sites for its sequestration have been deliberately made more gas-permeable by ‘fracking’ as a means of increasing the yield of petroleum-rich rock. Finally, a litre of injected gas can drive out pretty much the same volume of oil. So this approach to CCS may yield a greater potential for greenhouse warming than would the sequestered carbon dioxide itself.

Another, less widely publicised approach is to geochemically bind CO2 into solid carbonates, such as calcite (CaCO3), dolomite (CaMgCO3), or magnesite (MgCO3). Once formed such crystalline solids are unlikely to break down to their component parts at the surface, under water or buried. One way of doing this is by the chemical weathering of rocks that contain calcium- and magnesium-rich minerals, such as feldspar (CaAl2Si2O8), olivine ([Fe,Mg]2SiO4) and pyroxene ([Fe,Mg]CaSi2O6) . Mafic and ultramafic rocks, such as basalt and peridotite are commonly composed of such minerals. One approach involves pumping the gas into a Icelandic borehole that passes through basalt and letting natural reactions do the trick. They give off heat and proceed quickly, very like those involved in the setting of concrete. In two experimental field trials 95% of injected CO2 was absorbed within 18 months. Believe it or not, ants can do the trick with crushed basalt and so too can plant roots. There have been recent experiments aimed at finding accelerants for such subsurface weathering (Wang, J. et al. 2024. CO2 capture, geological storage, and mineralization using biobased biodegradable chelating agents and seawater. Science Advances, v. 10, article eadq0515; DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adq0515). In some respects the approach is akin to fracking. The aim is to connect isolated natural pores to allow fluids to permeate rock more easily, and to release metal ions to combine with injected CO2.

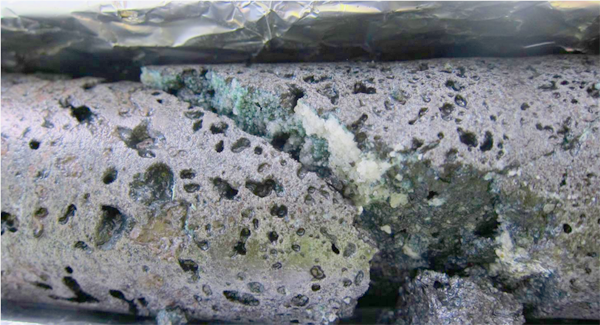

Chelating agents are biomolecules that are able to dissolve metal ions; some are used to remove toxic metals, such as lead, mercury and cadmium, from the bodies of people suffering from their effects. Naturally occurring ones extract metal ions from minerals and rocks and are agents of chemical weathering; probably used by the aforesaid ants and root systems. Wang and colleagues, based at Tohoku University in Japan, chose a chelating agent GLDA (tetrasodium glutamate diacetate – C9H9NNa4O8) derived from plants, which is non-toxic, cheap and biodegradable. They injected CO2 and seawater containing dissolved GDLA into basaltic rock samples. The GDLA increases the rock’s porosity and permeability by breaking down its minerals so that Ca and Mg ions entered solution and were thereby able to combine with the gas to form carbonate minerals. Within five days porosity was increased by 16% and the rocks permeability increased by 26 times. Using electron microscopy the authors were able to show fine particles of carbonate growing in the connected pores. In fact these carbonate aggregates become coated with silica released by the induced mineral-weathering reactions. Calculations based on the previously mentioned field experiment in Iceland suggest that up to 20 billion tonnes of CO2 could be stored in 1.3 km3 of basalt treated in this way: about 1/25000 of the active rift system in Iceland (3.3 x 104 km2 covered by 1 km of basalt lava). In 2023 fossil fuel use emitted an estimated 36.6 bllion tons of CO2 into the atmosphere.

So, why do such means of efficiently reducing the greenhouse effect not receive wide publicity by governments or the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change? Answers on a yellow PostIt™ please . . .