Plot the times of peaks in the rates of extinction during the Mesozoic against those of flood basalt outpourings closest in time to the die-offs and a straight line can be plotted through the data. There is sufficiently low deviation between it and the points that any statistician would agree that the degree of fit is very good. Many geoscientists have used this empirical relationship to claim that all Mesozoic mass extinctions, including the three largest (end-Permian, end-Triassic and end-Cretaceous) were caused in some way by massive basaltic volcanism. The fact that the points are almost evenly spaced – roughly every 30 Ma, except for a few gaps – has suggested to some that there is some kind of rhythm connecting the two very different kinds of event.

Leaving aside that beguiling periodicity, the hypothesis of a flood-basalt – extinction link has a major weakness. The only likely intermediary is atmospheric, through its composition and/or climate; flood volcanism was probably not violent. Both probably settle down quickly in geological terms. Moreover, flood basalt volcanism is generally short-lived (a few Ma at most) and seems not to be continuous, unlike that at plate margins which is always going on at one or other place. The great basalt piles of Siberia, around the Central Atlantic margins and in Western India are made up of individual thick and extensive flows separated by fossil soils or boles. This suggests that magma blurted out only occasionally, and was separated by long periods of normality; say between 10 and 100 thousand years. Evidence for the duration of major accelerations, either from stratigraphy and palaeontology or from proxies such as peaks and troughs in the isotopic composition of carbon (e.g. EPN Ni life and mass extinction) is that they too occurred swiftly; in a matter of tens of thousand years. Most of the points on the flood-basalt – extinction plot are too imprecise in the time dimension to satisfy a definite relationship. Opinion has swung behind an instantaneous impact hypothesis for the K-P boundary event rather than one involving the Deccan Traps in India, simply because the best dating of the Deccan suggests extinction seems to have occurred when no flows were being erupted, while the thin impact-related layer in sediments the world over is exactly at the point dividing Cretaceous flora and fauna from those of the succeeding Palaeogene.

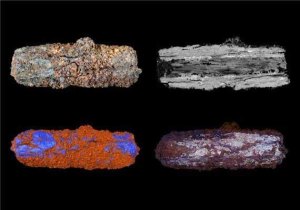

Yet no such link to an extraterrestrial factor is known to exist for any other major extinctions, so volcanism seems to be ‘the only game in town’ for the rest. Until basalt dating is universally more precise than it has been up to the present the case is ‘not proven’; but, in the manner of the Scottish criminal law, each is a ‘cold case’ which can be reopened. The previous article hardens the evidence for a volcanic driver behind the greatest known extinction at the end of the Permian Period. And in short-order, another of the Big Five seems to have been resolved in the same way. A flood basalt province covering a large area of west and north-west Australia (known as the Kalkarindji large igneous province)has long been known to be of roughly Cambrian age but does it tie in with the earliest Phanerozoic mass extinction at the Lower to Middle Cambrian boundary? New age data suggests that it does at the level of a few hundred thousand years (Jourdan, F. et al. 2014. High-precision dating of the Kalkarindji large igneous province, Australia, and synchrony with the Early-Middle Cambrian (Stage 4-5) extinction. Geology, v. 42, p. 543-546). The Kalkarindji basalts have high sulfur contents and are also associated with widespread breccias that suggest that some of the volcanism was sufficiently explosive to have blasted sulfur-oxygen gases into the stratosphere; a known means of causing rapid and massive climatic cooling as well as increasing oceanic acidity. The magma also passed through late Precambrian sedimentary basins which contain abundant organic-rich shales that later sourced extensive petroleum fields. Their thermal metamorphism could have vented massive amounts of CO2 and methane to result in climatic warming. It may have been volcanically-driven climatic chaos that resulted in the demise of much of the earliest tangible marine fauna on Earth to create also a sudden fall in the oxygen content of the Cambrian ocean basins.