In August 2024 Earth-Logs reported on the fragile nature of thermohaline circulation of ocean water. The post focussed on the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC), whose fickle nature seems to have resulted in a succession of climatic blips during the last glacial-interglacial cycle since 100 ka ago. They took the form of warming-cooling cycles known as Dansgaard-Oeschger events, when the poleward movement of warm surface water in the North Atlantic Ocean was disrupted. An operating AMOC normally drags northwards warm water from lower latitudes, which is more saline as a result of evaporation from the ocean surface there. Though it gradually cools in its journey it remains warmer and less dense than the surrounding surface water through which it passes: it effectively ‘floats’. But as the north-bound, more saline stream steadily loses energy its density increases. Eventually the density equals and then exceeds that of high-latitude surface water, at around 60° to 70°N, and sinks. Under these conditions the AMOC is self-sustaining and serves to warm the surrounding land masses by influencing climate. This is especially the case for the branch of the AMOC known as the Gulf Stream that today swings eastwards to ameliorate the climate of NW Europe and Scandinavia as far as Norway’s North Cape and into the eastern Arctic Ocean.

The suspected driving forces for the Dansgaard-Oeschger events are sudden massive increases in the supply of freshwater into the Atlantic at high northern latitudes, which dilute surface waters and lower their density. So it becomes more difficult for surface water to become denser on being cooled so that it can sink to the ocean floor. The AMOC may weaken and shut down as a result and so too its warming effect at high latitudes. It also has a major effect on atmospheric circulation and moisture content: a truly complicated climatic phenomenon. Indeed, like the Pacific El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO), major changes in AMOC may have global climatic implications. QIyun Ma of the Alfred Wegner Institute in Bremerhaven, Germany and colleagues from Germany, China and Romania have modelled how the various possible locations of fresh water input may affect AMOC (Ma, Q. et al. 2024. Revisiting climate impacts of an AMOC slowdown: dependence on freshwater locations in the North Atlantic. Science Advances, v. 10, article eadr3243; DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adr3243). They refer to such sudden inputs as ‘hosing’!

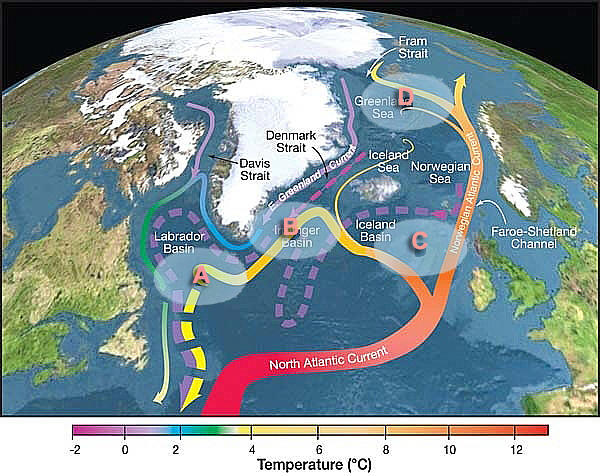

First, the likely consequences under current climatic conditions of such ‘hosings’ and AMOC collapses are: a rapid expansion of the Arctic Ocean sea ice; delayed onset of summer ice-free conditions; southward shift of the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) – a roughly equatorial band of low pressure where the NE and SE trade winds converge, and the rough location of the sometimes windless Doldrums. There have been several attempts to model the general climatic effects of an AMOC slowdown. Ma et al. take matters a step further by using the Alfred Wegener Institute Climate Model (AWI-CM3) to address what may happen following ‘hosing’ in four regions of the North Atlantic: the Labrador Sea (between Labrador and West Greenland); the Irminger Basin (SE of East Greenland, SW of Iceland); the Nordic Seas (north of Iceland; and the Greenland-Iceland-Norwegian seas) and the NE Atlantic (between Iceland, Britain and western Norway).

Prolonged freshwater flow into the Irminger Basin has the most pronounced effect on AMOC weakening, largely due to a U-bend in the AMOC where the surface current changes from northward to south-westward flow parallel to the East Greenland Current. The latter carries meltwater from the Greenland ice sheet whose low density keeps it near the surface. In turn, this strengthens NE and SW winds over the Labrador Sea and Nordic Seas respectively, which slow this part of the AMOC. In turn that complex system slows the entire AMOC further south. Since 2010 an average 270 billion tonnes of ice has melted in Greenland each year. This results in an annual 0.74 mm rise in global sea level, so the melted glacial ice is not being replenished. When sea ice forms it does not take up salt and is just as fresh as glacial ice. Annual melting of sea ice therefore temporarily adds fresh water to surface waters of the Arctic Ocean, but the extent of winter sea ice is rapidly shrinking. So, it too adds to freshening and lowering the density of the ocean-surface layer. The whole polar ocean ‘drains’ southwards by surface currents, mainly along the east coast of Greenland potentially to mix with branches of the AMOC. At present they sink with cooled more saline water to move at depth. To melting can be added calving of Greenlandic glaciers to form icebergs that surface currents transport southwards. A single glacier (Zachariae Isstrom) in NE Greenland lost 160 billion tonnes of ice between 1999 and 2022. Satellite monitoring of the Greenland glaciers suggests that a trillion tonnes have been lost through iceberg formation during the first quarter of the 21st century. Accompanying the Dansgaard-Oeschger events of the last 100 ka were iceberg ‘armadas’ (Heinrich events) that deposited gravel in ocean-floor sediments as far south as Portugal.

The modelling done by Ma et al. also addresses possible wider implications of their ‘hosing’ experiments to the global climate. The authors caution that this aspect is an ‘exploration’ rather than prediction. Globally increased duration of ‘cold extremes’ and dry spells, and the intensity of precipitation may ensue from downturns and potential collapse of AMOC. Europe seems to be most at risk. Ma et al. plea for expanded observational and modelling studies focused on the Irminger Basin because it may play a critical role in understanding the mechanisms and future strength of the AMOC.

See also: Yirka, R. 2024. Greenland’s meltwater will slow Atlantic circulation, climate model suggests. Phys Org, 21 November 2024