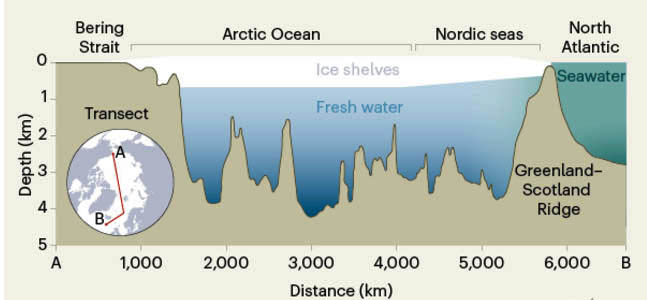

Climate during the last Ice Age was continually erratic. Generally fine-grained muds cored from the floor of the North Atlantic Ocean show repeated occurrences of layers containing gravelly debris. These have been ascribed to periods when ice sheets on Greenland and Scandinavia calved icebergs at an exceptionally fast rate, to release coarse debris as they melted while drifting to lower latitudes. These ‘iceberg armadas’ (known as Heinrich events) left their unmistakable signs as far south as Portugal. Their timing correlates with short-lived (1 to 2 ka) warming-cooling episodes (Dansgaard-Oeschger events) recorded in Greenland ice cores that involved variations in air temperature of up to 15°C. The process that resulted in these sudden climate shifts seems to have been changing ocean circulation brought about by vast amounts of fresh water flooding into the Arctic and North Atlantic Oceans. This lowered seawater density to the extent that its upper parts could not sink when cooled. It is this thermohaline circulation that drags warmer surface water northwards, known as the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC), part of which is the Gulf Stream. When it fails or slows the result is plummeting temperatures at high latitudes. The last major AMOC shutdown was after 8 ka of warming that followed the last glacial maximum. Between 12.9 and 11.7 ka major glaciers grew again north of about 50°N in the period known as the Younger Dryas, almost certainly in the aftermath of a flood to the Arctic Ocean of glacial meltwater from the Canadian Shield. Around 8.2 thousand years ago human re-colonisation of Northern Europe was set back by a similar but lesser cooling event.

Three researchers at Utrecht University, the Netherlands have issued an early warning that the AMOC may have reached a critical condition (Van Westen, R.M., Kliphuis, M & Dijkstra, H.A. 2024. Physics-based early warning signal shows that AMOC is on tipping course. Science Advances, v. 10, article adl1189; DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adk1189). Previous modelling of AMOC has suggested that only rapid, massive decreases in the salinity of North Atlantic surface water near the Arctic Circle could shut down the Gulf Stream in the manner of Younger Dryas and Dansgaard-Oeschger events. René van Westen and colleagues have simulated the effects of steady, long-term addition of fresh water from melting of the Greenland ice sheet. They ran a sophisticated Earth System model for six months on the Netherlands’ Snellius super computer. Their model used a slowly increasing influx of glacial meltwater to the Atlantic at high northern latitudes.

The various feedbacks in the model eventually shut down the AMOC, predicted to result in cooling of NW Europe by 10 to 15 °C in a matter of a few decades. Yet to achieve that required the model to simulate more than 2000 years of change. It took 1760 years for a persistent AMOC transport of 10 to 15 million m3 s-1 to drop over a century or so and reach near-zero. That collapse involved around 80 times more melting of Greenland’s ice sheet than at present. Yet their modelling does not take into account global warming: including that factor would have exceeded their budgeted supercomputer time by a long way. Melting of the Greenland ice sheet is, however, accelerating dramatically

Van Westen et al. have shown the possibility that steadily increasing ice-sheet melting can, theoretically, ’flip’ the huge current system associated with the Atlantic Ocean, and with it regional climate patterns. The tangible fear today is of a more than 1.5°C increase in global surface temperature, yet a warming-induced failure of AMOC may cause local annual temperatures to fall by up to ten times that. Rather than the currently heralded disappearance of sea-ice from the Arctic Ocean, it may spread in winter to as far south as the North Sea. The only way of forecasting in detail what may actually happen – and where – is ever-more sophisticated and costly modelling of ocean currents and ice melting in a warming world. Uncertain as it stands, the work by van Westen and colleagues may well be ignored: perhaps as a ‘thing we dinnae care to speak aboot’.

See also: Le Page, M. 2024. Atlantic current shutdown is a real danger, suggests simulation. New Scientist, 9 February 2024; Watts, J. 2024. Atlantic Ocean circulation nearing ‘devastating’ tipping point, study finds. The Guardian, 9 February 2024.