The molecules that make up all living matter are almost entirely (~98 %) made from the elements Carbon, Hydrogen, Oxygen, Nitrogen and Phosphorus (CHONP) in order of their biological importance. All have low atomic numbers, respectively 6th, 1st, 8th, 7th and 15th in the Periodic Table. Of the 98 elements found in nature, about 7 occur only because they form in the decay schemes of radioactive isotopes. Only the first 83 (up to Bismuth) are likely to be around ‘for ever’; the fifteen heavier than that are made up exclusively of unstable isotopes that will eventually disappear, albeit billions of years from now. There are other oddities that mean that the 92 widely accepted to be naturally occurring is not strictly correct. That CHONP are so biologically important stems partly from their abundances in the inorganic world and also because of the ease with which they chemically combine together. But they are not the only ones that are essential.

About 20 to 25% of the other elements are also literally vital, even though many are rare. Most of the rest are inessential except in vanishingly small amounts that do no damage, and may or may not be beneficial. However some are highly toxic. Any element can produce negative biological outcomes if above certain levels. Likewise, deficiencies can result in ill thrift and event death. For the majority of elements, biologists have established concentrations that define deficiency and toxic excess. The World Health Organisation has charted the maximum safe levels of elements in drinking water in milligrams per litre. In this regard, the lowest safe level is for thallium (Tl) and mercury (Hg) at 0.002 mg l-1.Other highly toxic elements are cadmium (Cd) (0.003 mg l-1), then arsenic (As) and lead (Pb) (0.01 mg l-1) that ‘everyone knows’ are elements to avoid like the plague. In nature lead is very rarely at levels that are unsafe because it is insoluble, but arsenic is soluble under reducing conditions and is currently responsible for a pandemic of related ailments, especially in the Gangetic plains of India and Bangladesh and similar environments worldwide.

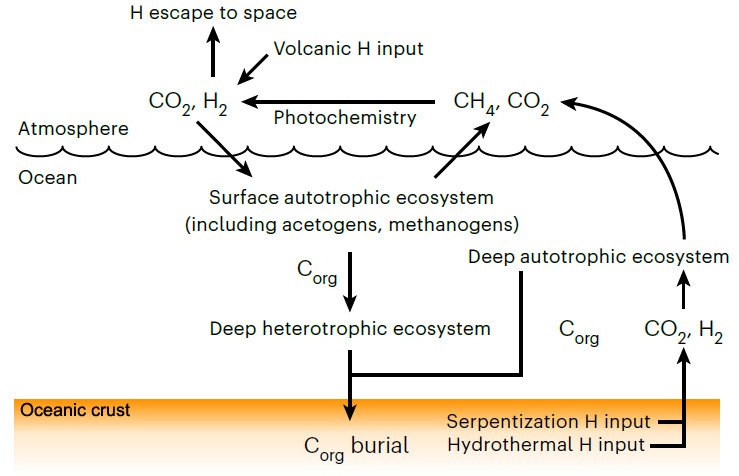

Biological evolution has been influenced since life appeared by the availability, generally in water, of both essential and toxic elements. In 2020 Earth-logs summarised a paper about modern oxygen-free springs in Chile in which photosynthetic purple sulfur bacteria form thick microbial mats. The springs contain levels of arsenic that vary from high in winter to low in summer. This phenomenon can only be explained by some process that removes arsenic from solution in summer but not in winter. The purple-bacteria’s photosynthesis uses electrons donated by sulfur, iron-2 and hydrogen – the spring water is highly reducing so they thrive in it. In such a simple environment this suggested a reasonable explanation: the bacteria use arsenic too. In fact they contain a gene (aio) that encodes for such an eventuality. The authors suggested that purple sulfur bacteria may well have evolved before the Great Oxygenation Event (GOE). They reasoned that in an oxygen-free world arsenic, as well as Fe2+ would be readily available in water that was in a reducing state, whereas oxidising conditions after the GOE would suppress both: iron-2 would be precipitated as insoluble iron-3 oxides that in turn efficiently absorb arsenic (see: Arsenic hazard on a global scale, May 2020).

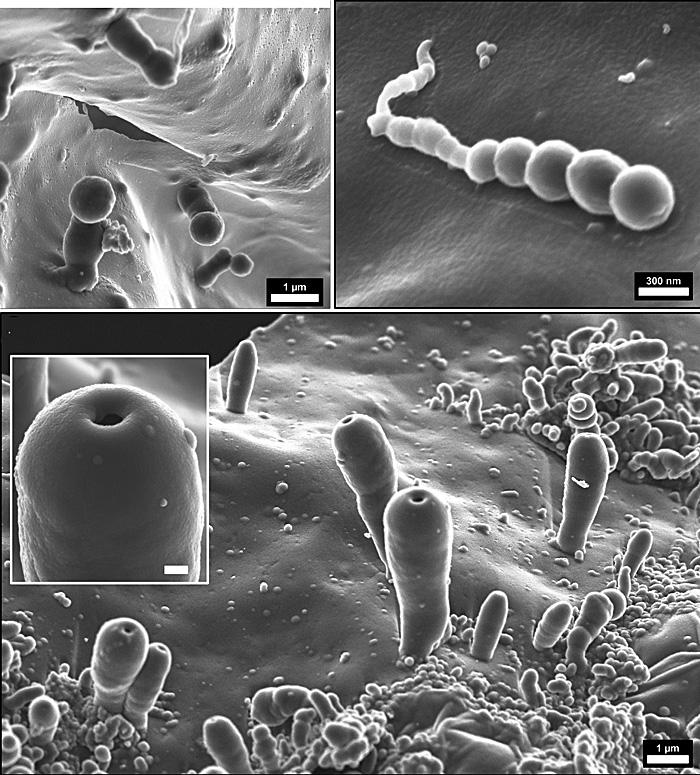

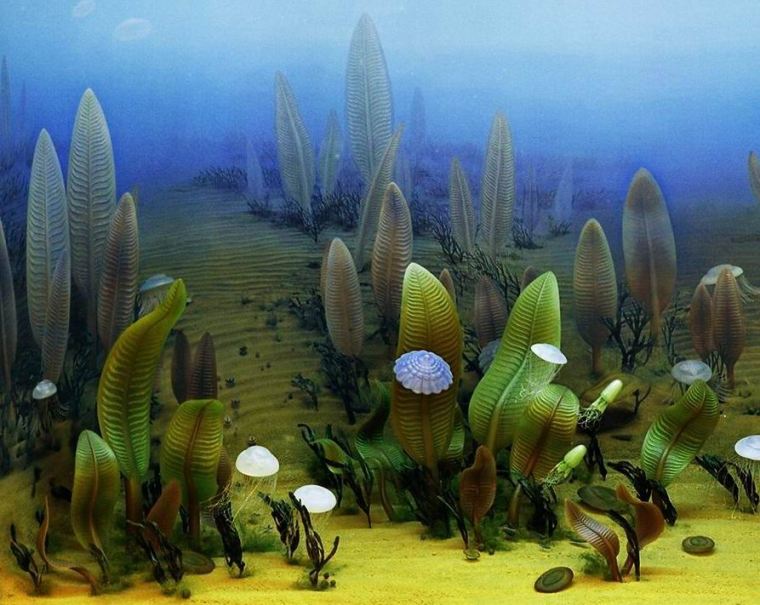

A group of geoscientists from France, the UK, Switzerland and Austria have investigated the paradox of probably high arsenic levels before the GOE and the origin and evolution of life during the Archaean (El Khoury et al. 2025. A battle against arsenic toxicity by Earth’s earliest complex life forms. Nature Communications, v. 16, article 4388; DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-59760-9). Note that the main, direct evidence for Archaean life are fossilized microbial mats known as stromatolites, some palaeobiologists reckoning they were formed by oxygenic photosynthesising cyanobacteria others favouring the purple sulfur bacteria (above). The purple sulfur bacteria in Chile and other living prokaryotes that tolerate and even use arsenic in their metabolism clearly evolved that potential plus necessary chemical defence mechanisms, probably when arsenic was more available in the anoxic period before the GOE. Anna El Khoury and her colleagues sought to establish whether or not eukaryotes evolved similar defences by investigating the earliest-known examples; the 2.1 Ma old Francevillian biota of Gabon that post-dates the GOE. They are found in black shales, look like tiny fried eggs and are associated with clear signs of burrowing. The shales contain steranes that are breakdown products of steroids, which are unique to eukaryotes.

The fossils have been preserved by precipitation of pyrite (Fe2S) granules under highly reducing conditions. Curiously, the cores of the pyrite granules in the fossils are rich in arsenic, yet pyrite grains in the host sediments have much lower As concentrations. The latter suggest that seawater 2.1 Ma ago held little dissolved arsenic as a result of its containing oxygen. The authors interpret the apparently biogenic pyrite’s arsenic cores as evidence of the organism having sequestered As into specialized compartments in their bodies: their ancestors must have evolved this efficient means of coping with significant arsenic stress before the GOE. It served them well in the highly reducing conditions of black shale sedimentation. Seemingly, some modern eukaryotes retain an analogue of a prokaryote As detoxification gene.