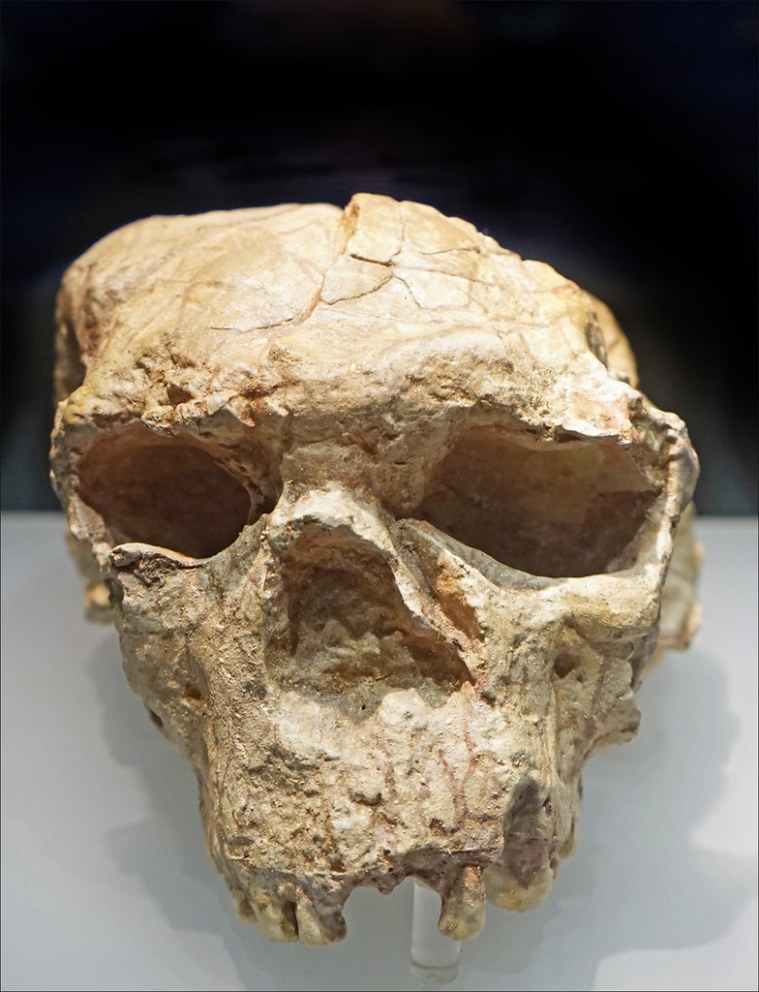

For over a century Chinese scientists have been puzzling over ancient human skulls that show pronounced brow ridges. Some assigned them to Homo, others to species that they believe were unique to China. A widely held view in China was that people now living there evolved directly from them, adhering to the ‘Multiregional Evolution’ hypothesis as opposed to that of ‘Out of Africa’. However, the issue might now have been resolved. In the last few years palaeoanthropologists have begun to suspect that these fossilised crania may have been Denisovans, but none had been subject to genetic and proteomic analysis. The few from Siberia and Tibet that initially proved the existence of Denisovans were very small: just a finger bone and teeth. Out of the blue, teeth in a robust hominin mandible dredged from the Penghu Channel between Taiwan and China yielded protein sequences that matched proteomic data from Denisovan fossils in Denisova Cave and Baishiya Cave in Tibet, suggesting that Denisovans were big and roamed widely in East Asia. In 2021 a near-complete robust cranium came to light that had been found in the 1930s near Harbin in China and hidden – at the time the area was under Japanese military occupation. It emerged only when its finder revealed its location in 2018, shortly before his death. It was provisionally called Homo longi or ‘Dragon Man’. Qiaomei Fu of the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology in Beijing and her colleagues have made a comprehensive study of the fossil.

It is at least 146 ka old, probably too young to have been H. erectus, but predates the earliest anatomically modern humans to have reached East Asia from Africa (~60 ka ago). The Chinese scientists have developed protein- and DNA extraction techniques akin to those pioneered at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig. It proved impossible to extract sufficient ancient nuclear DNA from the cranium bone for definitive genomic data to be extracted, but dental plaque (calculus) adhering around the only surviving molar in the upper jaw did yield mitochondrial DNA. The mtDNA matched that found in Siberian Denisovan remains (Qiaomei Fu et al. 2025. Denisovan mitochondrial DNA from dental calculus of the >146,000-year-old Harbin cranium. Cell, v. 188, p. 1–8; DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2025.05.040). The bone did yield 92 proteins and 122 single amino acid polymorphisms, as well as more than 20 thousand peptides (Qiaomei Fu and 8 others 2025. The proteome of the late Middle Pleistocene Harbin individual. Science, v. 388: DOI: 10.1126/science.adu9677). Again, these established a molecular link with the already known Denisovans, specifically with one of the Denisova Cave specimens. Without the painstaking research of the Chinese team, Denisovans would have been merely a genome and a proteome without much sign of a body! From the massive skull it is clear that they were indeed big people with brains much the same size as those of living people. Estimates based on the Harbin cranium suggest an individual weighing around 100 kg (220 lb or ~15 stone): a real heavyweight or rugby prop!

The work of Qiaomei Fu and her colleagues, plus the earlier, more limited studies by Tsutaya et al., opens a new phase in palaeoanthropology. Denisovans now have a genome and well-preserved parts of an entire head, which may allow the plethora of ancient skulls from China to be anatomically assigned to the species. Moreover, by extracting DNA from dental plaque for the first time they have opened a new route to obtaining genomic material: dental calculus is very much tougher and less porous than bone.

See also: Curry, A. ‘Dragon Man’ skull belongs to mysterious human relative. 2025. Science, v. 388; DOI: 10.1126/science.z8sb68w. Smith K. 2025. We’ve had a Denisovan skull since the 1930s – only nobody knew. Ars Technica, 18 June 2025. Marshall, M. 2025. We finally know what the face of a Denisovan looked like. New Scientist 18 June 2025.