The emergence of the eukaryotes – of which we are a late-entry member – has been debated for quite a while. In 2023 Earth-logs reportedthat a study of ‘biomarker’ organic chemicals in Proterozoic sediments suggests that eukaryotes cannot be traced back further than about 900 Ma ago using such an approach. At about the same time another biomarker study showed signs of a eukaryote presence at around 1050 Ma. Both outcomes seriously contradicted a ‘molecular-clock’ approach based on the DNA of modern members of the Eukarya and estimates of the rate of genetic mutation. That method sought to deduce the time in the past when the last eukaryotic common ancestor (LECA) appeared. It pointed to about 2 Ga ago, i.e. a few hundred million years after the Great Oxygenation Event got underway. Since eukaryote metabolism depends on oxygen, the molecular-clock result seems reasonable. The biomarker evidence does not. But were the Palaeo- and Mesoproterozoic Eras truly ‘boring’? A recent paper by Dietmar Müller and colleagues from the Universities of Sydney and Adelaide, Australia definitely shows that geologically they were far from that (Müller, R.D. et al. 2025. Mid-Proterozoic expansion of passive margins and reduction in volcanic outgassing supported marine oxygenation and eukaryogenesis. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, v. 672; DOI: 10.1016/j.epsl.2025.119683).

From 1800 to 800 Ma two supercontinents– Nuna-Columbia and Rodinia – aggregated nearly all existing continental masses, and then broke apart. Continents had collided and then split asunder to drift. So plate tectonics was very active and encompassed the entire planet, as Müller et al’s palaeogeographic animation reveals dramatically. Tectonics behaved in much the same fashion through the succeeding Neoproterozoic and Phanerozoic to build-up then fragment the more familiar supercontinent of Pangaea. Such dynamic events emit magma to form new oceanic lithosphere at oceanic rift systems and arc volcanoes above subduction zones, interspersed with plume-related large igneous provinces and they wax and wane. Inevitably, such partial melting delivered carbon dioxide to the atmosphere. Reaction on land and in the rubbly flanks of spreading ridges between new lithosphere and dissolved CO2 drew down and sequestered some of that gas in the form of solid carbonate minerals. Continental collisions raised the land surface and the pace of weathering, which also acted as a carbon sink. But they also involved metamorphism that released carbon dioxide from limestones involved in the crustal transformation. This protracted and changing tectonic evolution is completely bound up through the rock cycle with geochemical change in the carbon cycle.

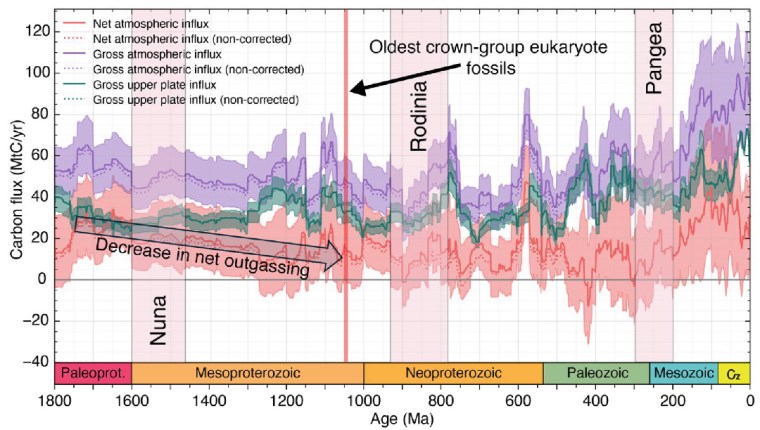

From the latest knowledge of the tectonic and other factors behind the accretion and break-up of Nuna and Rodinia, Müller et al. were able to model the changes in the carbon cycle during the ‘boring billion’ and their effects on climate and the chemistry of the oceans. For instance, about 1.46 Ga ago, the total length of continental margins doubled while Nuna broke apart. That would have hugely increased the area of shallow shelf seas where living processes would have been concentrated, including the photosynthetic emission of oxygen. In an evolutionary sense this increased, diversified and separated the ecological niches in which evolution could prosper. It also increased the sequestration of greenhouse gas through reactions on the flanks of a multiplicity of oceanic rift systems, thereby cooling the planet. Translating this into a geochemical model of the changing carbon cycle (see figure) suggests that the rate of carbon addition to the atmosphere (outgassing) halved during the Mesoproterozoic. The carbon cycle and probable global cooling bound up with Nuna’s breakup ended with the start of Rodinia’s aggregation about 1000 Ma ago and the time that biomarkers first indicate the presence of eukaryotes.

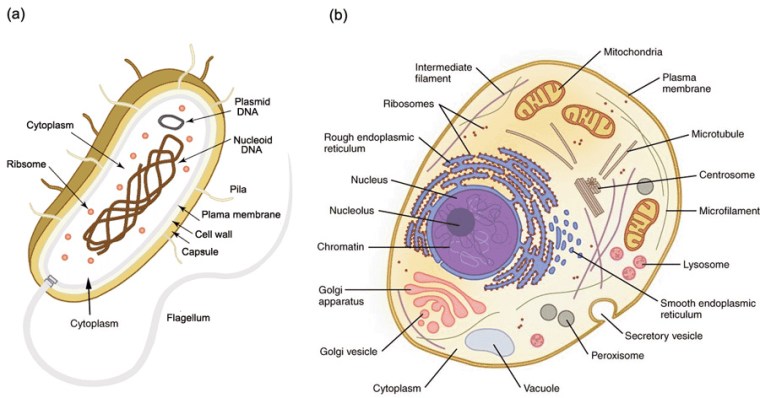

So, did tectonics play a major role in the rise of the Eukarya? Well, of course it did, as much as it was subsequently the changing background to the appearance of the Ediacaran animals and the evolutionary carnival of the Phanerozoic. But did it affect the billion-year delay of ‘eukaryogenesis’ during prolonged availability of the oxygen that such a biological revolution demanded? Possibly not. Lyn Margulis’s hypothesis of the origin of the basic eukaryote cell by a process of ‘endosymbiosis’ is still the best candidate 50 years on. She suggested that such cells were built from various forms of bacteria and archaea successively being engulfed within a cell wall to function together through symbiosis. Compared with prokaryote cells those of the eukaryotes are enormously complex. At each stage the symbionts had to be or become compatible to survive. It is highly unlikely that all components entered the relationship together. Each possible kind of cell assembly was also subject to evolutionary pressures. This clearly was a slow evolutionary process, probably only surviving from stage to stage because of the global presence of a little oxygen. But the eukaryote cell may also have been forced to restart again and again until a stable form emerged.

See also: New Clues Show Earth’s “Boring Billion” Sparked the Rise of Life. SciTechDaily, 3 November 2025