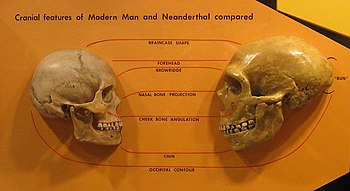

Despite the excitement raised by the discovery of remnants of 15 individuals of Homo naledi in a South African Cave the richest trove of hominin fossils remains that of Sima de los Huesos (‘pit of bones’) in northern Spain. In 2013 bone found in that cave from one of 28 or more individuals of what previous had been regarded as H. heidelbergensis, dated at around 400 ka, yielded mitochondrial DNA. It turned out to have affinities with mtDNA of both Neanderthals and Denisovans, especially the second. The data served to further complicate the issue of our origins, but were insufficient to do more than throw some doubt on the significance of H. heidelbergensis as a distinct species: nuclear DNA would do better, it was hoped by the palaeo-geneticists of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig. Now a small fragment of those data (about 1 tro 2 million base pairs) have been presented to a London meeting of the European Society for the Study of Human Evolution – though not yet in a peer-reviewed journal. Anne Gibbons summarised the formal presentation in the 18 September 2015 issue of Science (Gibbons, Ann 2015. Humanity’s long, lonely road. Science, v. 349, p. 1270).

The partial nuclear DNA is a great deal more like that of Neanderthals from much more recent times than it is of either Denisovans and modern humans. It seems most likely that the Sima de los Huesos individuals are early Neanderthals, which implies that the Neanderthal-Denisovan split was earlier than 400 ka. That might seem to be just fine, except for one thing: Neanderthal and Denisovan DNA are much more closely related to each other than to that of ourselves. That implies that the last common ancestor of the two archaic human species must have split from the ancestral line leading to modern humans even further back in time: maybe 550 to 765 ka ago and 100 to 400 ka earlier than previously surmised. This opens up several interesting possibilities for our long and separate development. Since Neanderthals and perhaps Denisovans emigrated from Africa to Eurasia several glacial cycles ago, maybe people genetically en route to anatomically modern humans did so too. The Neanderthal and Denisovan genomes suggest that they interbred with each other and that could have been at any time after the genetic split between them. Famously, they also interbred with direct ancestors of living Eurasians, but there is no genetic sign of that among living Africans. The evidence suggests that the insertion of archaic genetic material was into new migrants from Africa around 100 to 60 ka ago at different points along their routes to Europe and East Asia. But, obviously, it is by no means clear cut what passed between all three long-lived groups nor when. It is now just as possible that surviving, earlier Eurasians on the road to modern humans passed on their own inheritance from relationships with Neanderthal and Denisovan to newcomers from Africa. But none of these three genetic groups ever made their way back to Africa, until historic times.

More on Neanderthals, Denisovans and anatomically modern humans