Along with algae, jellyfish, oak trees, sharks and nearly every organism that can be seen with the naked eye, we are eukaryotes. The cells of every member of the Eukarya, one of the three great domains of life, all contain a nucleus – the main location of genetic material – and a variety of other small bodies known as organelles, such as the mitochondria of animals and the chloroplasts of plant cells. The vast bulk of organisms that we can’t see unaided are prokaryotes, divided into the domains of Bacteria and Archaea. Their genetic material floats around in their cells’ fluid. The DNA of eukaryotes shares some stretches with prokaryotes, but no prokaryotes contain any eukaryote genetic material. This suggests that the Eukarya arose after the Bacteria and Archaea, and also that they are a product of evolution from prokaryotes, probably by several combining in symbiotic relationships inside a shared cell membrane. Earth-logs has followed developments surrounding this major issue since 2002, as reflected in some of the posts linked to what follows.

While prokaryotes can live in every conceivable environment at the Earth’s surface and even in a few kilometres of crust beneath, the vast majority of eukaryotes depend on free oxygen for their metabolism. Logically, the earliest of the Eukarya could only have emerged when oxygen began to appear in the oceans following the Great Oxidation Event around 2.4 billion years ago. That is more than a billion years after the first prokaryotes had left their geological signature in the form of curiously bulbous, layered carbonate structures (stromatolites), probably formed by bacterial mats. The oldest occur in the Archaean rocks of Western Australia as far back as 3.5 Ga, and disputed examples have been found in the 3.7 Ga Isua sediments of West Greenland. The oldest of them are thought to have been produced through the anoxygenic photosynthesis of purple bacteria (See: Molecular ‘fossils’ and the emergence of photosynthesis; September 2000), suggested by organic molecules found in kerogen from early Archaean sediments. Later stromatolites (<3.0 Ga) have provided similar evidence for oxygen-producing cyanobacteria.

Acritarchs are microfossils of single-celled organisms made of kerogen that have been found in sediments up to 1.8 billion years old. Features protruding from their cell walls distinguish them from prokaryote cells, which are more or less ‘smooth’: acritarchs have been considered as possible early eukaryotes. Yet the oldest undisputed eukaryote microfossils – red and green algae – are much younger (about 1.0 Ga). A means of estimating an age for the crown group from which every later eukaryote organism evolved – last eukaryotic common ancestor (LECA) – is to use an assumed rate of mutation in DNA to deduce the time when differences in genetics between living eukaryotes began to diverge: i.e. a ‘molecular clock’. This gives a time around 2 Ga ago, but the method is fraught with uncertainties, not the least being the high possibility of mutation rates changing through time. So, when the Eukarya arose is blurred within the so-called ‘boring billion’ of the early Proterozoic Eon. A way of resolving this uncertainty to some extent is to look for ‘biomarker’ chemicals in the geological record that provide a ‘signature’ for eukaryotes.

A new study has been undertaken by a group of Australian, German and French scientists to analyse sediments ranging in age from 635 to 1640 Ma from Australia, China, Asia, Africa, North and South America (Brocks, J.J and 9 others 2023. Lost world of complex life and the late rise of the eukaryotic crown. Nature, v. 618, p. 767–773; DOI: 10.1038/s41586-023-06170-w; contact for PDF). Their chosen biomarkers are sterols (steroids) that regulate eukaryote cell membranes. Some prokaryotes also synthesise steroids but all of them produce hopanepolyols (hopanoids), which eukaryotes do not. The key measures for the presence/absence of eukaryote remains in ancient sea-floor sediments is thus the relative proportions of preserved steroids and hopanoids, together with those for the breakdown products of both – steranes and hopanesthat are, crudely speaking, carbon ‘skeletons’ of the original chemicals.

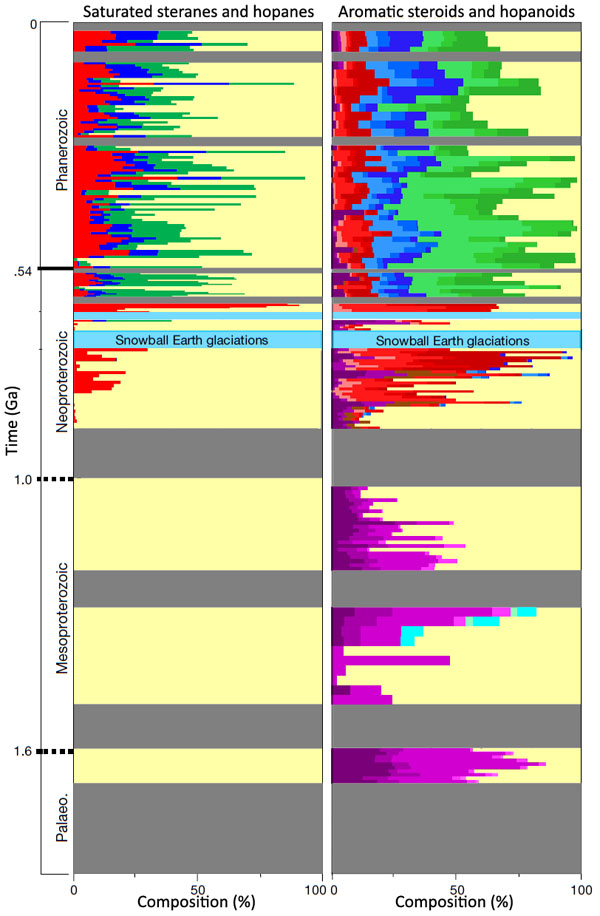

Interpretation of the results by Jochen Brocks and colleagues is complicated, and what follows is a summary based partly on an accompanying Nature News & Views article(Kenig, F. 2023. The long infancy of sterol biosynthesis. Nature, v. 618, p. 678-680; DOI: 10.1038/d41586-023-01816-1). The conclusions of Brocks et al. are surprising. First, the break-down products of steroids (saturated steranes) that can be attributed to crown eukaryotes (left on the figure above) are only present in sediments going back to about 200 Ma before the first Snowball Earth event (~900 Ma). Before that only hopanes formed by hopanoid degradation are present: a suggestion that LECA only appeared around that time – the authors suggest sometime between 1 and 1.2 Ga. That is far later than the time when eukaryotes could have emerged: i.e. once there was available oxygen after the Great Oxidation Event (~2.4 to 2.2 Ga). So what was going on before this? The authors broke new ground in analysis of biomarkers by being able to detect signs of the presence of actual hopanoids and steroids of several different kinds. Steroids were present as far back as 1.6 Ga in the oldest sediments that were analysed.

Steroids of crown eukaryotes are represented by cholesteroids, ergosteroids and stigmasteroids. All three are present throughout the Phanerozoic Eon and into the time of the Ediacaran Fauna that began 630 Ma ago. In that time span they generally outweigh hopanoids, thus reflecting the dominance of eukaryotes over prokaryotes. Back to about 900 Ma, only cholesteroids are present, together with archaic forms that are not found in living Eukarya, termed protosteroids. Before that, only protosteroids are found. Moreover, these archaic steroids are not present in sediments that follow the Snowball Earth episodes (the Cryogenian Period).

Thus, it is possible that crown group eukaryotes – and their descendants, including us – evolved from and completely replaced an earlier primitive form (acritarchs?) at around the time of the greatest climatic changes that the Earth had experienced in the previous billion years or more. Moreover, the Cryogenian and Ediacaran Periods seem to show a rapid emergence of stigmasteroid- and ergosteroid production relative to cholesteroid: perhaps a result of explosive evolution of the Eukarya at that time. The organisms that produced protosteroids were present in variable amounts throughout the Mesoproteroic. Clearly there need to be similar analyses of sediments going back to the Great Oxygenation Event and the preceding Archaean to see if the protosteroid producers arose along with increasing levels of molecular oxygen. The ‘boring billion’ (2.0 to 1.0 Ga) may well be more interesting than previously thought.