Charles Darwin famously suggested that humans evolved from apes, and since great apes (chimpanzees, bonobos and gorillas) live in Africa he reckoned it was probably there that the human ‘line’ began. Indeed, the mitochondrial DNA of chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) is the closest to that of living humans. Palaeoanthropology in Africa has established evolutionary steps during the Pleistocene (2.0 to 0.3 Ma) by early members of the genus Homo: H. habilis, H. ergaster, H. erectus; H. heidelbergensis and the earliest H. sapiens. Members of the last three migrated to Eurasia, beginning around 1.8 Ma with the individuals found at Dmanisi in Georgia. The earliest African hominins emerged through the Late Miocene (7.0 to 5.3 Ma): Sahelanthropus tchadensi, Orrorin tugenensis and Ardipthecus kadabba. Through the Pliocene (5.3 to 2.9 Ma) and earliest Pleistocene two very distinct hominin groups appeared: the ‘gracile’ australopithecines (Ardipithecus ramidus; Australopithecus anamensis; Au. afarensis; Au. africanus; Au. sediba) and the ‘robust’ paranthropoids (Paranthropus aethiopicus; P. robustus and P. boisei). The last of the paranthropoids cohabited East Africa with early homo species until around 1.4 Ma. Most of these species have been covered in Earth-logs and an excellent time line of most hominin and early human fossils is hosted by Wikipedia.

All apes, including ourselves, and fossil examples are members of the Family Hominidae (hominids) which refers to the entire world. A Subfamily (Homininae) refers to African apes, with two Tribes. One, the Gorillini, refers to the two living species of gorilla. The other is the Hominini (hominins) that includes chimpanzees, living humans and all fossils believed to be on the evolutionary line to Homo. The Tribe Hominini is defined to have descended from the common ancestor of modern humans and chimps, and evolved only in Africa. As the definition of hominins stands, it excludes other possibilities! The Miocene of Africa before 7.2 Ma ‘goes cold’ as regards the evolution of hominins. There are, however fossils of other African apes in earlier Miocene strata (8 to 18 Ma) that have been assigned to the Family Hominidae, i.e. hominids, of which more later.

Much has been made of using a ‘molecular clock’ to hint at the length of time since the mtDNA of living humans and chimps began to diverge from their last common ancestor. That is a crude measure at it depends entirely on assuming a fixed rate at which genetic mutation in primates take place. Many factors render it highly uncertain, until ancient DNA is recovered from times before about 400 ka, if ever. The approach suggests a range from 7 to 10 Ma, yet the evolutionary history of chimps based on fossils is practically invisible: the earliest fossil of a member of genus Pan is from the Middle Pleistocene (1.2 to 0.8 Ma) of Kenya. Indeed, we have little if any clue about what such a common ancestor looked like or did. So the course of human evolution relies entirely on the fossil sequence of earlier African hominins and comparing their physical appearances. Each species in the African time line displays two distinctive features. All were bipedal and had small canine teeth. Modern chimps habitually use knuckle walking except when having to cross waterways. As with virtually all other primates, fossil or living, male chimps have large, threatening canines. In the absence of ancient DNA from fossils older than 0.4 Ma these two features present a practical if crude way of assessing to when and where the hominin time line leads.

In 2002 a Polish geologist on holiday at the beach at Trachilos on Crete discovered a trackway on a bedding plane in shallow-marine Miocene sediments. It had been left by what seems to have been a bipedal hominin. Subsequent research was able to date the footprints to about 6.05 Ma. Though younger than Sahelanthropus, the discovery potentially challenges the exclusivity of hominins to Africa. Unsurprisingly, publication of this tentative interpretation drew negative responses from some quarters. But the discovery helped resurrect the notion that Africa may have been colonised in the Miocene by hominins that had evolved in Europe. That had been hinted at by the 1872 excavation of Oreopithecus bambolii from an Upper Miocene (~7.6 Ma) lignite mine in Tuscany, Italy – a year after publication of Darwin’s The Descent of Man.

Lignites in Tuscany and Sardinia have since yielded many more specimens, so the species is well documented. Oreopithecus could walk on two legs, its hands were capable of a precision grip and it had relatively small canines. Its Wikipedia entry cautiously refers to it as ‘hominid’ – i.e. lumped with all apes to comply with current taxonomic theory (above). In 2019 another fascinating find was made in a clay pit in Bavaria, Germany. Danuvius guggenmosi lived 11.6 Ma ago and fossilised remains of its leg- and arm bones suggested that it could walk on two legs: it too may have been on the hominin line. But no remains of Danuvius’s skull or teeth have been found. There is now an embarrassment of riches as regards Miocene fossil apes from Europe and the Eastern Mediterranean (Sevim-Erol, A. and 8 others 2023. A new ape from Türkiye and the radiation of late Miocene hominines. Nature Communications Biology, v. 6, article 842.; DOI: 10.1038/s42003-023-05210-5). A number of them closely resemble the earliest fossil hominins of Africa, but most predate the hominin record there by several million years.

Ayla Sevim-Erol of Ankara University, Turkiye and colleagues from Turkiye, Canada and the Netherlands describe a newly identified Miocene genus, Anadoluvius, which they place in the Subfamily Homininae dated to around 8.7 Ma. Fragments of crania and partial male and female mandibles from Anatolia show that its canines were small and comparable with those of younger African hominins, such as Ardipithecus and Australopithecus. But limb bones are yet to be found. Around the size of a large male chimpanzee, Anadoluvius lived in an ecosystem remarkably like the grasslands and dry forests of modern East Africa, with early species of giraffes, wart hogs, rhinos, diverse antelopes, zebras, elephants, porcupines, hyenas and lion-like carnivores. Sevim-Erol et al. have attempted to trace back hominin evolution further than is possible with African fossils. They compare various skeletal features of different fossils and living genera to assess varying degrees of similarity between each genus, applied to 23 genera. These comprised 7 hominids from the African Miocene, 2 early African hominins (Ardipithecus and Orrorin) and 10 Miocene hominids from Europe and the Eastern Mediterranean. They also assessed similarities with 4 living genera, Homo, orang utan (Pongo), gorilla and chimp (Pan).

The resulting phylogeny shows close morphological links within a cluster (green ‘pools’ on diagram) of non-African hominids with the African hominins, gorillas, humans and chimps. There are less-close relations between that cluster and the earlier Miocene hominids of Africa (blue ‘pool’) and the possible phylogeny of orang utans (orange ‘pool’). Sevim-Erol et al. note that African hominins are clearly more similar and perhaps more closely related to the fossils of Europe and the Eastern Mediterranean than they are to Miocene African hominids. This suggests that evolution among the non-African hominids ceased around the end of the Miocene Epoch north of the Mediterranean Sea. But it may have continued in Africa. Somehow, therefore, it became possible late in Miocene times for hominids to migrate from Europe to Africa. Yet the earlier, phylogenetically isolated African hominids seem to have ‘crashed’ at roughly the same time. Such a complex scenario cannot be supported by phylogenetic studies alone: it needs some kind of ecological impetus.

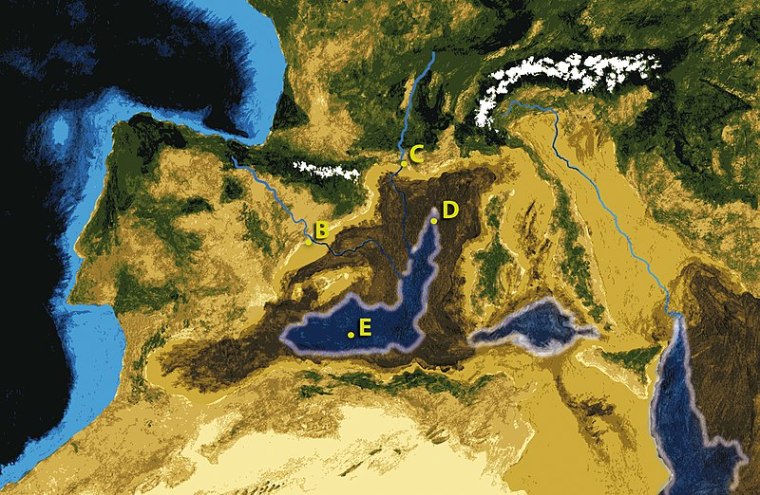

Following a ‘mild’ tectonic collision between the African continent and the Iberian Peninsula during the late Miocene connection between the Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea was blocked from 6.0 to 5.3 Ma. Except for its deepest parts, seawater in the Mediterranean evaporated away to leave thick salt deposits. Rivers, such as the Rhône, Danube, Dneiper and Nile, shed sediments into the exposed basin. For 700 ka the basin was a fertile, sub-sea level plain, connecting Europe and North Africa over and E-W distance of 3860 km. There was little to stop the faunas of Eurasia and Africa migrating and intermingling, at a critical period in the evolution of the Family Hominidae. One genus presented with the opportunity was quite possibly the last common ancestor of all the hominins and chimps. The migratory window vanished at the end of the Miocene when what became the Strait of Gibraltar opened at 5.3 to allow Atlantic water. This resulted in the stupendous Zanclean flood with a flow rate about 1,000 times that of the present-day Amazon River. An animation of these events is worth watching