Much of the Archaean Eon is represented by cratons, which occur at the core of continental parts of tectonic plates. Having low geothermal heat flow they are the most rigid parts of the continental crust. The Superior Craton is an area that makes up much of the eastern part of the Canadian Shield, and formed during the Late Archaean from ~4.3 to 2.6 billion years (Ga) ago. Covering an area in excess of 1.5 million km2, it is the world’s largest craton. One of its most intensely studied components is the Abitibi Terrane, which hosts many mines. A granite-greenstone terrain, it consists of volcano-sedimentary supracrustal rocks in several typically linear greenstone belts separated by areas of mainly intrusive granitic bodies. Many Archaean terrains show much the same ‘stripey’ aspect on the grand scale. Greenstone belts are dominated by metamorphosed basaltic volcanic rock, together with lesser proportions of ultramafic lavas and intrusions, and overlying metasedimentary rocks, also of Archaean age. Various hypotheses have been suggested for the formation of granite-greenstone terrains, the latest turning to a process of ‘sagduction’. However the relative flat nature of cratonic areas tells geologists little about their deeper parts. They tend to have resisted large-scale later deformation by their very nature, so none have been tilted or wholly obducted onto other such stable crustal masses during later collisional tectonic processes. Geophysics does offer insights however, using seismic profiling, geomagnetic and gravity surveys.

The Geological Survey of Canada has produced masses of geophysical data as a means of coping with the vast size and logistical challenges of the Canadian Shield. Recently five Canadian geoscientists have used gravity data from the Canadian Geodetic Survey to model the deep crust beneath the huge Abitibi granite-greenstone terrain, specifically addressing variations in its density in three dimensions. They also used cross sections produced by seismic reflection and refraction data along 2-D survey lines (Galley, C. et al. 2025. Archean rifts and triple-junctions revealed by gravity modeling of the southern Superior Craton. Nature Communications, v. 16, article 8872; DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-63931-z). The group found that entirely new insights emerge from the variation in crustal density down to its base at the Moho (Mohorovičić discontinuity). These data show large linear bulges in the Moho separated by broad zones of thicker crust.

Galley et al. suggest that the zones are former sites of lithospheric extensional tectonics and crustal thinning: rifts from which ultramafic to mafic magmas emerged. They consider them to be akin to modern mid-ocean and continental rifts. Most of the rifts roughly parallel the trend of the greenstone belts and the large, long-lived faults that run west to east across the Abitibi Terrain. This suggests that rifts formed under the more ductile lithospheric condition of the Neoarchaean set the gross fabric of the granites and greenstones. Moreover, there are signs of two triple junctions where three rifts converge: fundamental features of modern plate tectonics. However, both rifts and junctions are on a smaller scale than those active at present. The rift patterns suggest plate tectonics in miniature, perhaps indicative of more vigorous mantle convection during the Archaean Eon.

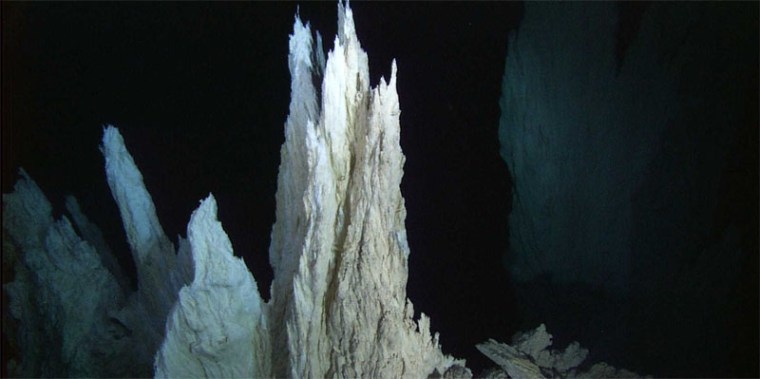

There is an interesting spin-off. The Abitibi Terrane is rich in a variety of mineral resources, especially volcanic massive-sulfide deposits (VMS). Most of them are associated with the suggested rift zones. Such deposits form through sea-floor hydrothermal processes, which Archaean rifting and triple junctions would have focused to generate clusters of ‘black smokers’ precipitating large amounts of metal sulfides. Galley et al’s work is set to be applied to other large cratons, including those that formed earlier in the Archaean: the Pilbara and Kaapvaal cratons of Australia and South Africa. That could yield better insights into earlier tectonic processes and test some of the hypotheses proposed for them

See also: Archaean Rifts, Triple Junctions Mapped via Gravity Modeling. Scienmag, 6 October 2025