Regular readers of Earth-logs will recall that the islands of Indonesia were reached by the archaic humans Homo erectus and H. floresiensis at least a million years ago. Anatomical comparison of their remains suggest that the diminutive H. floresiensis probably evolved from H. erectus under the stress of being stranded on the small, resource-poor island of Flores: a human example of island dwarfism. In fact there are anatomically modern humans (AMH) living on Flores that seem to have evolved dwarfism in the same way since AMH first arrived there between 50 and 5 ka. Incidentally, H. erectus fossils and artefacts were found by Eugene Dubois in the late 19th century at a famous site near Trinil in Java. In 2014, turned out that H. erectus had produced the earliest known art – zig-zag patterns on freshwater clam shells – between 540 and 430 ka ago. The episodic falls in global sea level due to massive accumulations of ice on land during successive Pleistocene glacial episodes aided migration by producing connections between the islands of SE Asia. They created a huge area of low-lying dryland known as ‘Sundaland’. The islands’ colonisation by H. erectus was made easy, perhaps inevitable.

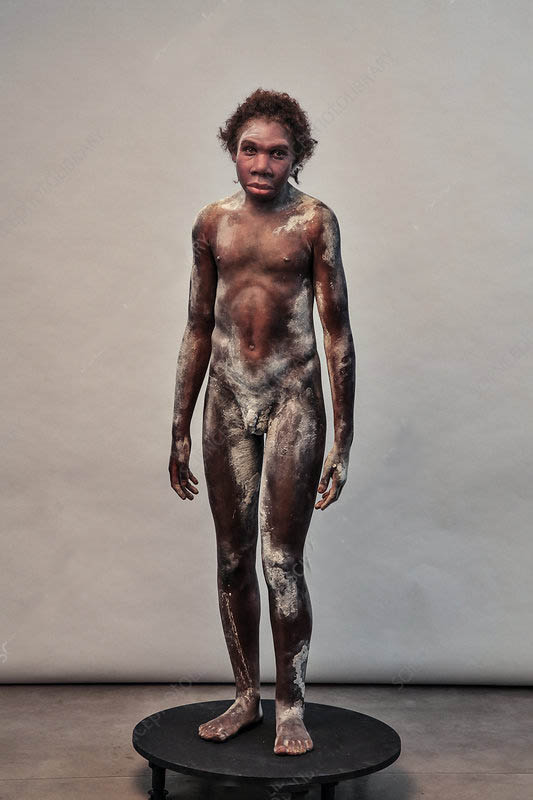

However, Flores and islands further east are separated from those to the west by a narrow but very deep strait. It channels powerful currents that are hazardous to small-boat crossings even today. Most palaeoanthropologists consider the colonisation of Flores by H. erectus most likely to have resulted by accident, reckoning that they were incapable of planning a crossing and building suitable craft. For AMH to have reached New Guinea and Australia around 60 ka ago, they must have developed sturdy craft and sea-faring skills. This paradigm suggests that the evolution of AMH, and thus their eventual occupation of all continents except Antarctica, must have involved a revolutionary ‘leap’ in their cognitive ability just before they left Africa. That view has been popularised by the presenter (Ella Al-Shamahi) of the 2025 BBC Television series Human – now on BBC iPlayer (requires viewers to create a free account) – in its second episode Into the Unknown. [The idea of a cognitive leap that ushered in the almost worldwide migration of anatomically modern humans was launched in 1995 by controversial anthropologist Chris Knight of University College London].

The large and peculiarly-shaped island of Sulawesi, also part of Indonesia, is notable for being the location of the earliest known figurative art; a cave painting of a Sulawesi warty pig, dated to at least 45.5 ka ago. Indonesian and Australian archaeologists working at a site near Calio in northern Sulawesi unearthed stone artefacts deep in river-terrace gravels that contain fossils of extinct pigs and dwarf elephants (Hakim, B. and 26 others 2025. Hominins on Sulawesi during the Early Pleistocene. Nature, v. 644;DOI: 10.1038/s41586-025-09348-6). The tools were struck from pebbles of hard fine-grained rocks by flaking to produce sharp edges. A combination of dating techniques – palaeomagnetism, uranium-series and electron-spin resonance – on the terrace sediments and fossils in them yielded ages ranging from 1.04 to 1.48 Ma; far older than the earliest known presence of AMH on the island (73–63 ka). The dates for an early human presence on Sulawesi tally with those from Flores. The tool makers were probably H. erectus. To reach the island from Sundaland at a time when global sea level was 120 m lower than at present would have required crossing more than 50 km of open water. It seems unlikely that such a journey could have been accidental. The migrants would have needed seaworthy craft; possibly rafts. Clearly the AMH crossings to New Guinea around 60 thousand years ago would have been far more daunting. Both land masses would have been below the horizon of any point of departure from the Indonesian archipelago, even with island ‘hopping’. Yet the Sulawesi discovery, combined with the plethora of islands both large and small, suggests that the earlier non-AMH inhabitants of Indonesia potentially could have spread further at times of very low sea level.

See also: Brumm, A. t al. 2025. This stone tool is over 1 million years old. How did its maker get to Sulawesi without a boat? The Conversation, 6 August 2025