There may still be a few people around today who, like Aristotle did, reckon that frogs form from May dew and that maggots and rats spring into life spontaneously from refuse. But the idea that life emerged somehow from the non-living is, to most of us, the only viable theory. Yet the question, ‘How?’, is still being pondered on. Readers may find Chapter 13 of Stepping Stones useful. There I tried to summarise in some detail most of the modern lines of research. But the issue boils down to means of inorganically creating the basic chemical building blocks from which life’s vast and complex array of molecules might have been assembled. Living materials are dominated by five cosmically common elements: carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen and phosphorus – CHONP for short. Organic chemists can readily synthesise countless organic compounds from CHONP. And astronomers have discovered that life is not needed to assemble the basic ingredients: amino acids, carbon-ring compounds and all kinds of simpler CHONP molecules occur in meteorites, comets and even interstellar molecular clouds. So an easy way out is to assume that such ingredients ended up on the early Earth simply because it grew through accretion of older materials from the surrounding galaxy. Somehow, perhaps, their mixing in air, water and sediments together with a kind of chaotic shuffling did the job, in the way that an infinity of caged monkeys with access to typewriters might eventually create the entire works of William Shakespeare. But, aside from the statistical and behavioural idiocy of that notion, there is a real snag: the vaporisation of the proto-Earth’s outer parts by a Moon-forming planetary collision shortly after initial accretion.

In 1871 Charles Darwin suggested to his friend Joseph Hooker that:

‘… if (and Oh, what a big if) we could conceive in some warm little pond, with all sorts of ammonia and phosphoric salts, light, heat, electricity, etc., present that a protein compound was chemically formed, ready to undergo still more complex changes, at the present day such matter would be instantly devoured or absorbed, which would never have been the case before living creatures were formed’.

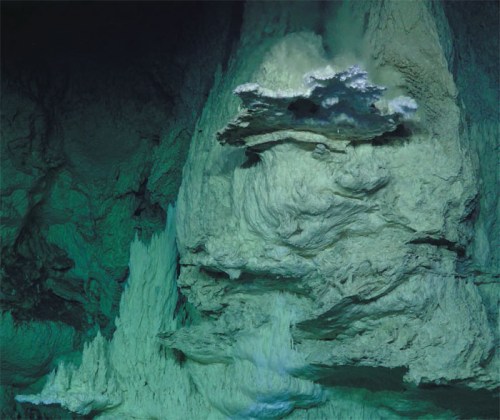

Followed up in the 1920s by theorists Alexander Oparin and J.B.S. Haldane, a similar hypothesis was tested practically by Harold Urey and Stanley Miller at the University of Chicago. They devised a Heath-Robinson simulation of an early atmosphere and ocean seeded with simple CHONP (plus a little sulfur) chemicals, simmered it and passed electrical discharges through it for a week. The resulting dark red ‘soup’ contained 10 of the 20 amino acids from which a vast array of proteins can be built. A repeat in 1995 also yielded two of the four nucleobases at the heart of DNA – adenine and guanine. But simply having such chemicals around is unlikely to result in life, unless they are continually in close contact: a vessel or bag in which such chemicals can interact. The best candidates for such a containing membrane are fatty acids of a form known as amphiphiles. One end of an amphiphile chain has an affinity for water molecules, whereas the other repels them. This duality enables layers of them, when assembled in water, spontaneously to curl up to make three dimensional membranes looking like bubbles. In the last year they too have been created in vitro (Purvis, G. et al. 2024. Generation of long-chain fatty acids by hydrogen-driven bicarbonate reduction in ancient alkaline hydrothermal vents. Nature Communications (Earth & Environment), v. 5, article 30; DOI: 10.1038/s43247-023-01196-4).

Graham Purvis and colleagues from Newcastle University, UK allowed three very simple ingredients – hydrogen and bicarbonate ions dissolved in water and the iron oxide magnetite (Fe3O4) – to interact. Such a simple, inorganic mixture commonly occurs in hydrothermal vents and hot springs. Bicarbonate ions (HCO3–) form when CO2 dissolves in water, the hydrogen and magnetite being generated during the breakdown of iron silicates (olivines) when ultramafic igneous rocks react with water:

3Fe2SiO4 + 2H2O → 2 Fe3O4 + 3SiO2 +3H2

Various simulations of hydrothermal fluids had previously been tried without yielding amphiphile molecules. Purvis et al. simplified their setup to a bicarbonate solution in water that contained dissolved hydrogen – a simplification of the fluids emitted by hydrothermal vents – at 16 times atmospheric pressure and a temperature of 90°C. This was passed over magnetite. Under alkaline conditions their reaction cell yielded a range of chain-like hydrocarbon molecules. Among them was a mixture of fatty acids up to 18 carbon atoms in length. The experiment did not incorporate P, but its generation of amphiphiles that can create cell-like structures are but a step away from forming the main structural components of cell membranes, phospholipids.

When emergence of bag-forming membranes took place is, of course, hard to tell. But in the oldest geological formations ultramafic lava flows are far more common than they are today. In the Hadean and Eoarchaean, even if actual mantle rocks had not been obducted as at modern plate boundaries, at the surface there would have been abundant source materials for the vital amphiphiles to be generated through interaction with water and gases: perhaps in ‘hot little ponds’. To form living, self-replicating cells requires such frothy membranes to have captured and held amino acids and nucleobases. Such proto-cells could become organic reaction chambers where chemical building blocks continually interacted, eventually to evolve the complex forms upon which living cells depend.