Debates around the origin of Earth’s life and what the first organism was like resemble the mythical search for the Holy Grail. Chivalric romanticists of the late 12th and early 13th centuries were pretty clear about the Grail – some kind of receptacle connected either with the Last Supper or Christ’s crucifixion – but never found it. Two big quests that engage modern science centre on how the chemical building blocks of the earliest cells arose and the last universal common ancestor (LUCA) of all living things. Like the Grail’s location, neither is likely to be fully resolved because they can only be sought in a very roundabout way: both verge on the imaginary. The fossil record is limited to organisms that left skeletal remains, traces of their former presence, and a few degraded organic molecules. The further back in geological time the more sedimentary rock has either been removed by erosion or fundamentally changed at high temperatures and pressures. Both great conundrums can only be addressed by trying to reconstruct processes and organisms that occurred or existed more than 4 billion years ago.

In the 1950s Harold Urey of the University of Chicago and his student Stanley Miller mixed water, methane, ammonia and hydrogen sulfide in lab glassware, heated it up and passed electrical discharges through it. They believed the simple set-up crudely mimicked Hadean conditions at the Earth surface. They were successful in generating more complex organic chemicals than their starting materials, though the early atmosphere and oceans are now considered to have been chemically quite different. Such a ‘Frankenstein’ approach has been repeated since with more success (see Earth-logs April 2024), creating 10 of the 20 amino acids plus the peptide bonds that link them up to make all known proteins, and even amphiphiles, the likely founders of cell walls. The latest attempt has been made by Spanish scientists at the Andalusian Earth Sciences Institute, the Universities of Valladolid and Cadiz, and the International Physics Centre in San Sebastian (Jenewein, C. et al 2024. Concomitant formation of protocells and prebiotic compounds under a plausible early Earth atmosphere. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, v. 122, article 413816122; DOI: 10.1073/pnas.241381612).

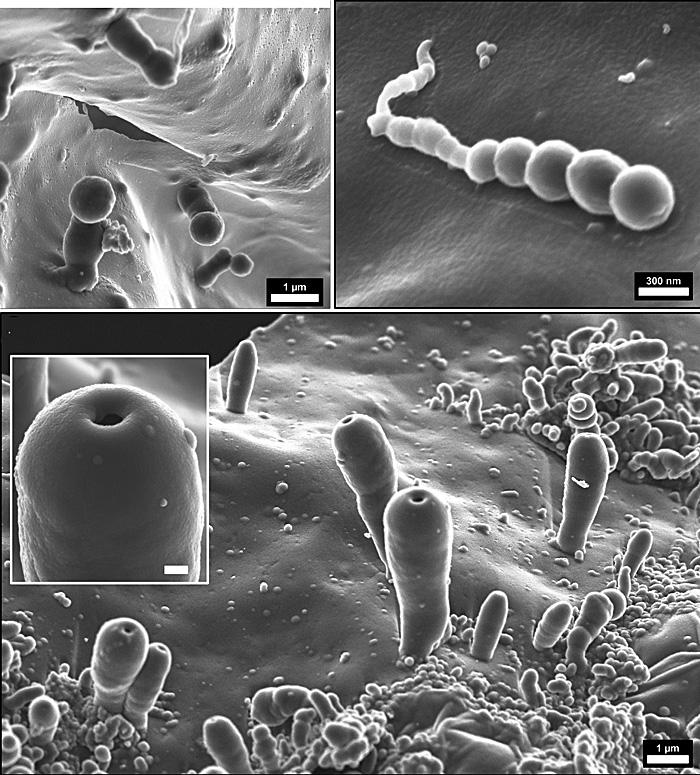

Jenewein and colleagues claim to have created cell-like structures, or ‘biomorphs’ at nanometre- and micrometre scale – spheres and polyp-like bodies – from a more plausible atmosphere of CO2 , H2O, and N2. These ‘protocells’ seem to have formed from minutely thin (150 to 3000 nanometres) polymer films built from hydrogen cyanide that grew on the surface of the reaction chamber as electric discharges and UV light generated HCN and more complex ‘prebiotic’ chemicals. Apparently, these films were catalysed by SiO2 (silica) molecules from the glass reactor. Note: In the Hadean breakdown of olivine to serpentinite as sea water reacted with ultramafic lavas would have released abundant silica. Serpentinisation also generates hydrogen. Intimate release of gas formed bubbles to create the spherical and polyp-like ‘protocells’. The authors imagine the Hadean global ocean permanently teeming with such microscopic receptacles. Such a veritable ‘primordial soup’ would be able to isolate other small molecules, such as amino acids, oligopeptides, nucleobases, and fatty acids, to generate more complex organic molecules in micro-reactors en route to the kind of complex, self-sustaining systems we know as life.

So, is it possible to make a reasonable stab at what that first kind of life may have been? It was without doubt single celled. To reproduce it must have carried a genetic code enshrined in DNA, which is unique not only to all species, but to individuals. The key to tracking down LUCA is that it represents the point at which the evolutionary trees of the fundamental domains of modern life life – eukarya (including animals, plants and fungi), bacteria, and archaea – converge to a single evolutionary stem. There is little point in using fossils to resolve this issue because only multicelled life leaves tangible traces, and the first of those was found in 2,100 Ma old sediments in Gabon (see: The earliest multicelled life; July 2010). The key is using AI to compare the genetic sequences of the hugely diverse modern biosphere. Modern molecular phylogenetics and computing power can discern from their similarities and differences the relative order in which various species and broader groups split from others. It can also trace the origins of specific genes that provides clues about earlier genetic associations. Given a rate of mutation the modern differences provide estimates of when each branching occurred. The most recent genetic delving has been achieved by a consortium based at various institutions in Britain, the Netherlands, Hungary and Japan (Moody, E.R.R. and 18 others 2024. The nature of the last universal common ancestor and its impact on the early Earth system. Nature Ecology & Evolution, v.8, pages 1654–1666; DOI: 10.1038/s41559-024-02461-1).

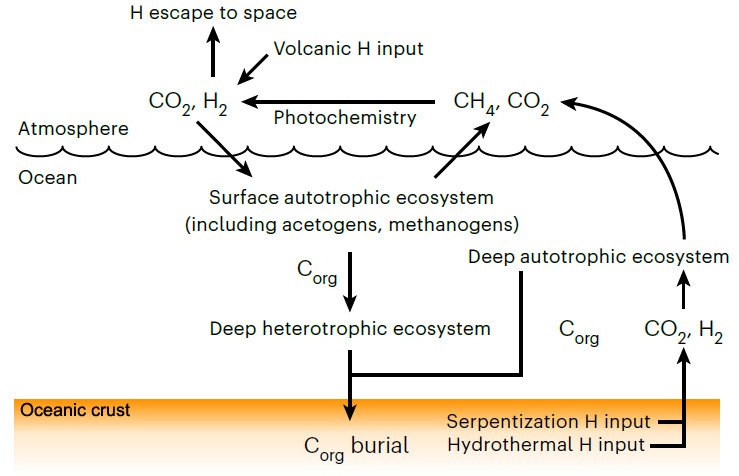

Moody et al have pushed back the estimated age of LUCA to halfway through the Hadean, between 4.09 to 4.33 billion years (Ga), well beyond the geologically known age of the earliest traces of life (3.5 Ga). That age for LUCA in itself is quite astonishing: it could have been only a couple of hundred million years after the Moon-forming interplanetary collision. Moreover, they have estimated that Darwin’s Ur-organism had a genome of around 2 million base pairs that encoded about 2600 proteins: roughly comparable to living species of bacteria and archaea, and thus probably quite advanced in evolutionary terms. The gene types probably carried by LUCA suggest that it may have been an anaerobic acetogen; i.e. an organism whose metabolism generated acetate (CH3COO−) ions. Acetogens may produce their own food as autotrophs, or metabolise other organisms (heterotrophs). If LUCA was a heterotroph, then it must have subsisted in an ecosystem together with autotrophs which it consumed, possibly by fermentation. To function it also required hydrogen that can be supplied by the breakdown of ultramafic rocks to serpentinites, which tallies with the likely ocean-world with ultramafic igneous crust of the Hadean (see the earlier paragraphs about protocells). If an autotroph, LUCA would have had an abundance of CO2 and H2 to sustain it, and may have provided food for heterotrophs in the early ecosystem. The most remarkable possibility discerned by Moody et al is that LUCA may have had a kind of immune system to stave off viral infection.

The Hadean environment was vastly different to that of modern times: a waterworld seething with volcanism; no continents; a target for errant asteroids and comets; more rapidly spinning with a 12 hour day; a much closer Moon and thus far bigger tides. The genetic template for the biosphere of the following four billion years was laid down then. LUCA and its companions may well have been unique to the Earth, as are their descendants. It is hard to believe that other worlds with the potential for life, even those in the solar system, could have followed a similar biogeochemical course. They may have life, but probably not as we know it . . .

See also: Ball, P. 2025. Luca is the progenitor of all life on Earth. But its genesis has implications far beyond our planet. The Observer, 19 January 2025.

A fully revised edition of Steve Drury’s book Stepping Stones: The Making of Our Home World can now be downloaded as a free eBook