Evidence from Dmanisi in Georgia that Homo erectus may have been the first advanced hominin to leave Africa about 1.8 Ma ago was a big surprise (see: First out of Africa? November 2003). Remains of five individuals included one skull of an aged person who face was so deformed that he or she must have been cared for by others for many years. So, a second surprise from Dmanisi was that human empathy arose far earlier than most people believed. Since 2002 there has been only a single further find of hominin bones of such antiquity, at Longgudong in central China. For the period between 1.0 and 2.0 Ma eight other sites in Eurasia have yielded hominin remains. If finds of stone tools and evidence of deliberate butchery – cut marks on prey animals’ bones – are accepted as tell-tale signs, the Eurasian hominin record is considerably larger, and longer,. There are 11 Eurasian sites that have yielded such evidence – but no hominin remains – that are older than Longgudong: in Russia, China, the Middle East, North Africa and northern India. The oldest, at Masol in northern India is 2.6 Ma old. In January 2025 the earliest European evidence for hominin activity was reported from Grăunceanu in Romania (Curran, S.C. and 15 others 2025. Hominin presence in Eurasia by at least 1.95 million years ago. Nature Communications, v. 16, article 836; DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-56154-9) in the form of animal bones showing clear signs of butchery, as well as stone tools, but no hominin fossils.

There were stone-tool makers who butchered prey in Africa as early as 3.4 Ma ago (see: Stone tools go even further back; May 2015), but without direct evidence of which hominin was involved. Several possible candidates have been suggested: Australopithecus; Kenyanthropus; Paranthropus. The earliest known African remains of H. erectus have been dated at around 2.0 Ma. So, all that can be said with some certainty about the pre-2 Ma migrants to Eurasia, until fossils of that antiquity are found, is that they were hominins of some kind: maybe advanced australopithecines, paranthropoids or early humans. Those from Longgudong and Dmanisi probably are early Homo erectus, and 2 others (1.7 and 1.6 Ma) from China have been designated similarly. Younger, pre-1.0 Ma Eurasian hominins from Israel, Indonesia, Spain and Turkey are currently un-named at the species level, but are allegedly members of the genus Homo.

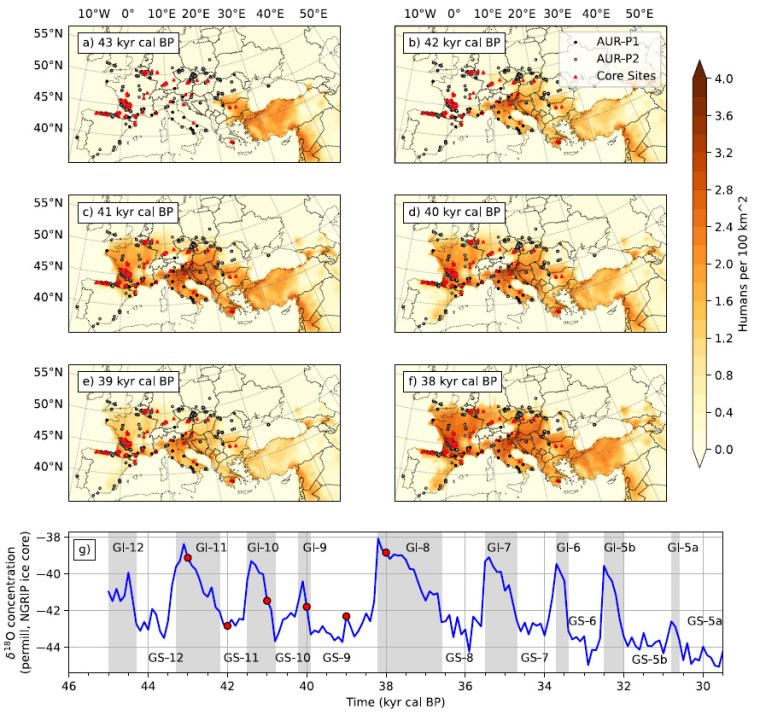

So, what can be teased from the early Eurasian hominin finds? Some certainly travelled thousands of kilometres from their assumed origins in Africa, but none penetrated further north than about 50°N. Perhaps they could not cope with winters at higher latitudes, especially during ice ages. To reach as far as eastern and western Eurasia suggests that dispersal following exit from Africa would have taken many generations. There is no reason to suppose continual travel; rather the reverse, staying put in areas with abundant resources while they remained available, and then moving on when they became scarce. Climate cycles, first paced at around 40 ka (early Pleistocene) then at around 100 ka (mid Pleistocene and later), would have been the main drivers for hominin population movements, as it would have been for game and vegetation.

After about 3 Ma the 40 ka climate cyclicity evolved to greater differences in global temperature between glacial and interglacial episodes, and even more so after the mid Pleistocene transition to 100 ka cycles (see Wikipedia entry for the mid-Pleistocene Transition). Thus, it seems likely that chances of survival of dispersed bands of hominins decreased over hundreds of millennia. Could populations have survived in particularly favourable areas; i.e. those at low latitudes? If so did both culture and the hominins themselves evolve? Alternatively, was migration in a series of pulses out of Africa and then dispersal in all directions, most ending in regional extinction? Almost certainly, pressures to leave Africa would have been driven by climate, for instance by increased aridity as global temperatures waned and sea-level falls made travel to Eurasia easier. There may also have been secondary, shorter migrations within Eurasia, again driven by environmental changes. Without more data from newly discovered sites we can go little further. Within the 35 known, pre-1 Ma hominin sites there are two clusters: southern and central China, and the Levant, Turkey and Georgia. Could they yield more developments? A 2016 article in Scientific American about Chinese H. erectus finds makes particularly interesting reading in this regard.

Neanderthals and the elusive Denisovans began to establish permanent Eurasian ranges, after roughly 600 ka ago. Both groups survived until after first contact with waves of anatomically modern humans in the last 100 ka, with whom some interbred before vanishing from the record. However, evidence from the DNA of both groups suggests an interesting possibility. Before the two groups split genetically, their common ancestors (H. heidelbergensis or H. antecessor?) apparently interbred with genetically more ancient Eurasian hominins (see Wikipedia entry for Neanderthal evolution). This intriguing hint suggests that more may be discovered when substantial remains of Denisovans – i.e. more than a few teeth and small bones – are discovered and yield more DNA. My guess is such a future development will stem from analysis of early hominin remains in China, currently regarded as H. erectus. See China discovers landmark human evolution fossils. Xinhua News Agency 9 December 2024)

A fully revised edition of Steve Drury’s book Stepping Stones: The Making of Our Home World can now be downloaded as a free eBook