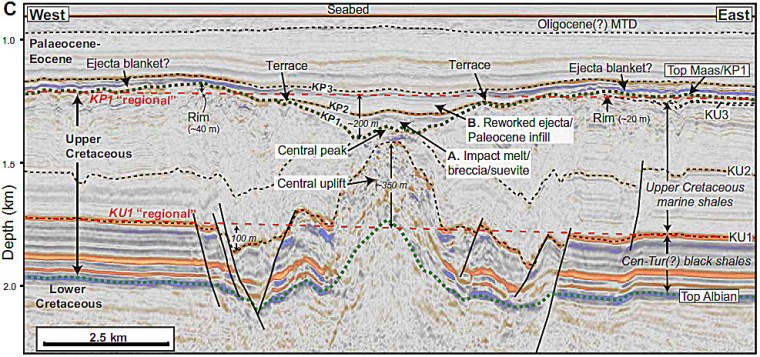

In 2022 four geoscientists from Heriot-Watt University in Edinburgh, Scotland and the Universities of Arizona and Texas (Austin), USA were geologically interpreting seismic-reflection data beneath the seafloor off Guinea and Guinea-Bissau, West Africa. Individual sedimentary strata that cover the upper continental crust show up as many reflectors. They are calibrated to rock cores from exploratory well that had revealed up to 8 km of sedimentary cover deposited continuously since the Upper Jurassic. The team’s objective was to collect information on tectonic structures that had formed when South America separated from Africa during the Cretaceous. The geophysical data were from commercial reconnaissance surveys aimed at locating petroleum fields beneath part of the West African continental shelf known as the Guinea Terrace. One of the seismic sections revealed a ~9 km wide basin-like depression at the level of the Cretaceous-Palaeogene boundary, which is underlain by a prominent upward bulge in reflectors corresponding to the mid-Cretaceous, plus a large number of nearby faults (Nicholson, U., and 3 others 2022. The Nadir Crater offshore West Africa: a candidate Cretaceous-Paleogene impact structure. Science Advances, v. 8, article eabn3096; DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.abn3096). Elsewhere on the Guinea Terrace the strata were featureless by comparison.

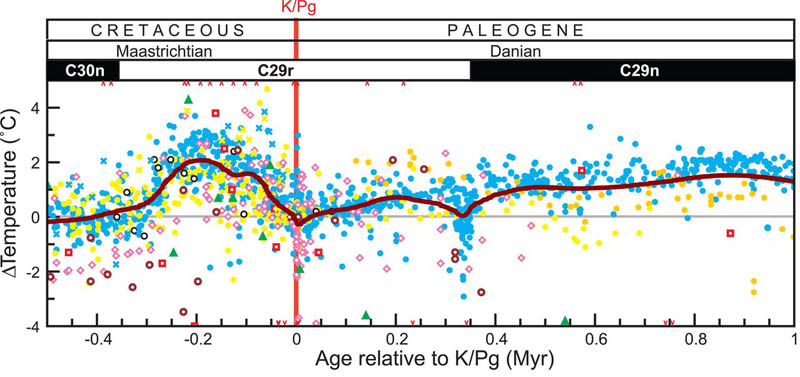

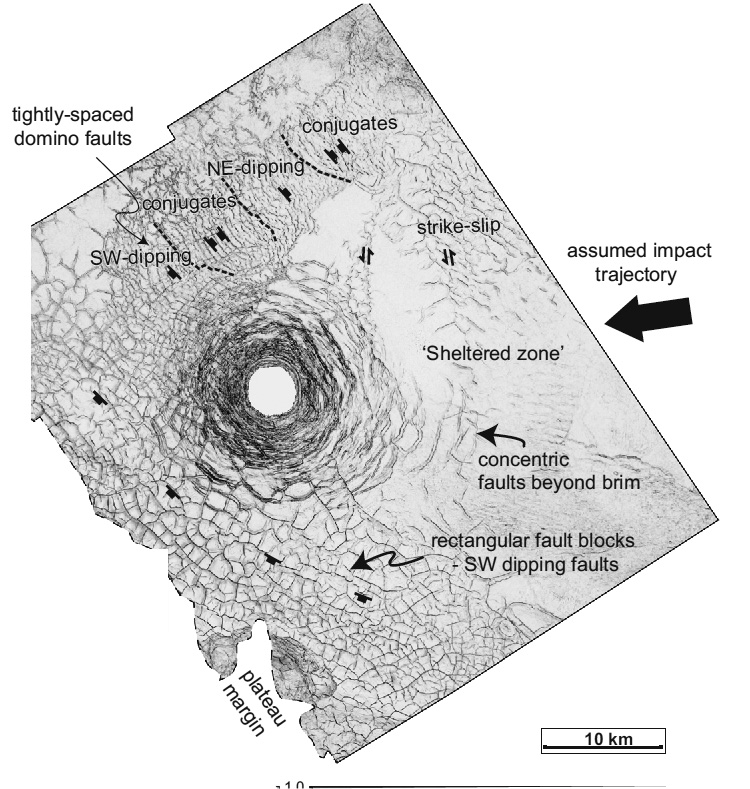

The Nadir crater showed many of the signs to be expected from an asteroid impact. That it drew attention stemmed partly from being of roughly the same age as the much larger 66 Ma Chicxulub impact off the Yucatan Peninsula of Mexico: the likely culprit for the K-Pg mass-extinction event. Perhaps both impactors stemmed from the break-up of a large, near-Earth asteroid because of gravitational forces resulting from a previous close encounter with either the Earth or another planet. The crater lies at the centre of a 23 km wide zone of faults that only affect Cretaceous and older strata; i.e. they formed just before the K-Pg event. The seismic data also show signs of widespread liquefaction of nearby Cretaceous sedimentary strata and that the crater had been filled by sediments shortly after it formed. Yet the data were too fuzzy for an astronomical catastrophe to be absolutely certain: similar structures can form from the rise of bodies of rock salt, which is less dense than sediments and will dissolve on reaching the seabed. The owners of the seismic data donated a much larger collection from a grid of survey lines. Processing of such seismic grids turns the collection of individual two-dimensional sections into a 3D regional data set showing the complete shape of subsurface structures. Seismic data of this kind enables more detailed structural and lithological interpretation of both cross section and plan views. They enable sedimentary layers to be ‘peeled’ back to examine the crater at all depths, in much the same manner as CT and MRI scans reveal the inner anatomy of the human body.

Uisdean Nicholson and a larger team have now published their findings from the 3D seismic data that show the structure in unique detail (Nicholson, U., and 6 others 2024. 3D anatomy of the Cretaceous–Paleogene age Nadir Crater. Communications Earth & Environment v. 5, article number 547; DOI: 10.1038/s43247-024-01700-4). Nadir crater was affected by spiral-shaped thrust faults that suggest it was formed by an oblique impact from the northeast by an object around 450 m across, probably travelling at 20 km s-1 at 20 to 40° to the surface. Seconds after excavation uplift of deeper sediments was a response to removal of the load on the crust. The energy was sufficient to vaporise both sediment and impactor within a few seconds, the to drive drive seawater outwards in a tsunami about half a kilometre high, which in about 30 seconds exposed the incandescent crater floor. In the succeeding minutes hours and days liquefied sea water sloshed in and out of the crater, repeated tsunami resurgence forming gullies on its flanks and transporting sediment mixed with glass (suevite) flowed to refill the crater.

There is no means of assigning any of the K-Pg extinctions to the Nadir crater, just that it happened at roughly the same time as Chicxulub. But it is the first impact crater to reveal the processes involved through complete coverage by high-resolution 3D seismic data. The majority of the roughly 200 craters are on the continental surface, and were thus ravaged to some extent by later erosion. Yet of the influx of hypervelocity objects through time at least 70% must have struck the oceans, but only 15 to 20 are known. That may reflect the fact that much deeper water could have buffered even giant impacts from affecting the oceanic crust beneath the abyssal plains, whose average depth is about 4 km. Only a small proportion of the continental shelves deemed to contain petroleum reserves have been explored seismically. Chicxulub itself has been drilled, but only two seismic reflection sections have crossed its centre since its discovery, although earlier 3D data from petroleum exploration cover its outermost northern parts. More detail is available for Nadir and its lower energy did not smash its structural results, unlike Chicxulub. So, despite Nadir’s smaller size, fortuitously it gives more clues to how such marine craters formed. It looks to be an irresistible target for drilling.