The division of the lunar surface into two petrological domains – ancient anorthositic highlands and younger basaltic maria – spurred the idea, as long ago as the early 1970s, that the early Moon had a deep ocean of magma at the surface, whose cooling caused fractional crystallization. Low density plagioclase feldspar, dominated by high-calcium anorthite and bytownite, floated to the surface to form the lunar anorthosites leaving a more mafic mantle from which the mare basalts formed by partial melting. The key evidence in support of this hypothesis lies in the rare-earth elements of the two terrains. Because plagioclase feldspar has a much stronger affinity to incorporate the element europium (Eu) than the other REEs, the lunar anorthosites are enriched in Eu compared with its related elements. If the highland anorthosites did form by fractional crystallisation the remaining magma that formed the lunar mantle would be depleted in Eu yet enriched in the remaining REE. Although there are no samples of the Moon’s mantle there are plenty of the mare basalts that formed when it partially melted, probably as a result of huge impacts around 3.8 billion years ago. They should have inherited dominant features of mantle geochemistry, and indeed they do show characteristic depletion of Eu.

The giant-impact hypothesis for the Earth-Moon system presupposes that such a cataclysm would have left much of the outer Earth in much the same molten condition and destined to fractionate in the same manner. There are geochemical hints from terrestrial rocks that do support such an idea. An important target for exploration of Mars has been to check if a magma ocean also existed early in its history. Of the various missions in recent years only two have the capacity to shed useful light on the issue: the US Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter and Mars Odyssey. Both orbiters carry more sophisticated remote sensing instruments than any circling the Earth. The first has the hyperspectral Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars (CRISM) that senses visible to short-wave infrared (VNIR) radiation, the other deploys the Thermal Emission Imaging System (THEMIS) that captures different parts of the longer wavelength thermal infrared (TIR) spectrum emitted by surface materials. Both allow spectra of surface materials to be reconstructed and compared with the features of known minerals from the Earth and Moon.

Feldspars are highly reflective for the most part of the VNIR range but show a shallow, broad absorption feature centred on a wavelength of 1.26 micrometres. Such spectra have been detected using CRISM from parts of the Martian surface in the highlands of its southern hemisphere (Carter, J. & Poulet, F. 2013. Ancient plutonic processes on Mars inferred from the detection of possible anorthositic terrains. Nature Geoscience, v. 6, p. 1008-1012). The authors, from Chile and France, acknowledge that the plagioclase-rich rocks occur only in small patches, unlike the vast tracts on the Moon, and also that on Earth anorthosites are known to have formed by a variety of processes from far smaller magma systems than a veritable ocean of molten rock. Feldspars also show spectral features in the TIR, though not so distinctive, both plagioclase and alkali feldspars being very similar. Moreover, THEMIS deploys sensor for only 10 thermal wavebands, compared with 544 on CRISM. A team of US remote sensers (Wray, J.J. and 8 others 2013. Prolonged magmatic activity on Mars inferred from the detection of felsic rocks. Nature Geoscience, v. 6, p. 1013-1017) used both CRISM and THEMIS data. While noting resemblances to lunar anorthosites, they adopt a more cautious approach to the spectra and prefer the broad, ‘sack’ term ‘felsic rocks’. It seemed possible from their work that feldspar-rich magmas may have formed by partial melting of common andesitic crust noted from the Martian surface: high spatial resolution images of the occurrences bear some resemblance to outcrops of granitic rocks in arid environments on Earth. That is, there may be highly evolved rocks akin to terrestrial continental crust.

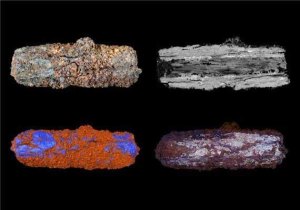

The interesting spectral observations on Mars can only be validated by actual rock samples. While rovers still operating on the Martian surface are well able to produce geochemical data that would petrologically characterise most rocks that they encounter, none of them is in a terrain suitable for resolving this particular issue. Yet, coincidentally, a meteorite found in West Africa shows hallmarks of having been blasted from the surface of Mars and sheds useful light on various hypotheses about the Martian crust http://earth-pages.co.uk/2013/11/21/a-glimpse-of-early-martian-crust/. It is a breccia that may represent the soil or regolith that accumulated from early impacts that shattered and melted surface materials, and it is extremely old: zircons yielded an age of 4428 Ma. The clasts set in a fine matrix consist of a variety of igneous rocks, none of which are anorthosites. Some are coarse grained, plutonic rocks containing both alkali feldspars and plagioclase, which match terrestrial monzonites; broadly speaking members of the granite family. Having formed from the ejecta of large impacts, such regolith materials represent the breadth of compositions across the planet and extending deep into its crust. This one suggests that anorthosites may have been rare on early Mars.

Related articles

- Mars once had oceans of liquid hot magma (abc.net.au)

- Evidence found for granite on Mars (eurekalert.org)

![Focusing the 100-millimeter Mastcam [detail] Focusing the 100-millimeter Mastcam [detail]](https://i0.wp.com/farm9.static.flickr.com/8285/7881867862_d0e33b1c87.jpg)