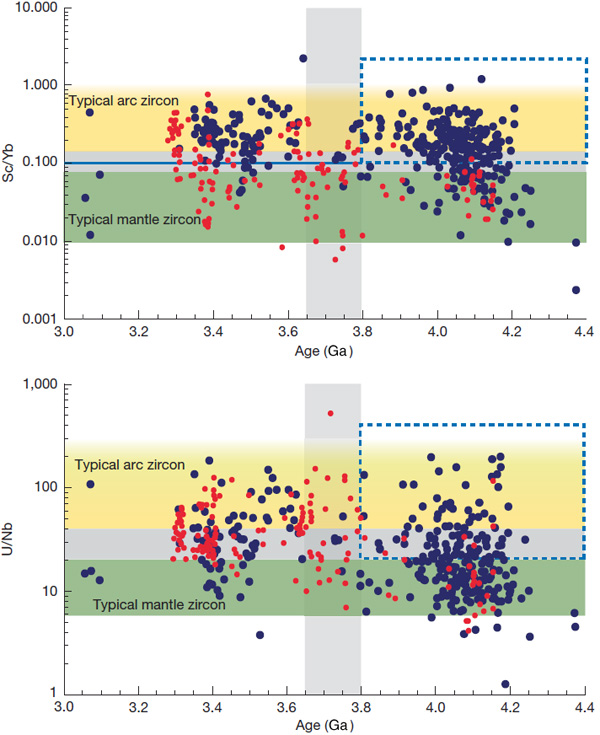

Over the last few decades improved analytical techniques have made it possible to analyse tiny mineral grains for a variety of trace elements and several isotopes. Zircons obtained directly from crushed granitic igneous rocks vary in chemistry according to the magmatic processes that generated them and their tectonic context. Elevated ratios between uranium and niobium (U/Nb) and scandium and ytterbium (Sc/Yb) are characteristic of zircons in intermediate granites. These contain 52 to 63 % SiO2 – between mafic and felsic magmas – which formed by melting of hydrated mafic crust in settings akin to modern continental arcs; i.e. in subduction zones. But such partial melting can also take place where the base of continental crust delaminates and ‘drips’ into the mantle. That process is part of what is known as stagnant lid tectonics, believed by many to have been important in the Palaeoarchaean and Hadean. Such a process would have involved nearly anhydrous conditions and thus different geochemical partitioning of elements in the magmas and minerals that crystallised from them. Exposures of crystalline continental crust become increasingly rare further back in geological time, and there are none older than 4.0 Ga – i.e. of Hadean age – with a granitic component. Consequently studying the generation of continental crust in the Hadean and the early Archaean is almost entirely dependent on ancient zircons that found their way into much younger sedimentary rocks. The most famous of these occur as detrital grains in the 3.6 Ga Jack Hills conglomerate of Western Australia. Others have been extracted from similar ~3.3 Ga sedimentary rocks in the Barberton Greenstone Belt of South Africa and Eswatini.

John Valley of the University of Wisconsin-Madison, USA, and co-workers from the US, Germany, Australia and France have worked on a large number of zircons newly extracted from Jack Hills. They have radiometrically dated them, and analysed Nb, Sc, U and Yb trace elements and hafnium (Hf) and oxygen isotopes Together with data from earlier studies, including Barberton zircons, they have teased out some remarkable insights into ‘continent-forming’ magmatism as far back in time as 4.4 billion years ago (Valley, J.W. and 11 others 2026. Contemporaneous mobile- and stagnant-lid tectonics on the Hadean Earth. Nature, Open access; DOI: 10.1038/s41586-025-10066-2). More than 70% of the >4.0 Ga Jack Hills zircons have elevated U/Nb and Sc/Yb ratios, which suggest that they formed in a setting akin to continental-arc subduction (CAS) zones, to produce now-vanished Hadean continental crust. The remainder seem to represent processes at mid-ocean ridge (MOR) and oceanic island (OI) settings. In contrast, the bulk of Barberton zircons of Hadean age show OI affinities, with only around 22% showing Nb–Sc–U–Yb signatures of probable CAS origins. From about 4.4 to 3.8 Ga two distinct forms of continental crust generation seem to have operated on Earth. In the erosional source region for the Barberton zircons their host granites seem to have formed during the Hadean and Eoarchaean by remelting of foundered lower crust, i.e. probably in a stagnant-lid-like tectonic setting. But at around 3.6 Ga they ‘flip’ to a subduction-like setting. The zircons yielded by Jack Hills conglomerates suggest substantially different conditions: alternating CAS and OI settings during the Hadean and a fall-off in crust generation during the Eoarchaean (4.0 to 3.8 Ga).

The mixed Hadean zircon signatures from Jack Hills possibly indicate that they were derived by erosion and transport from several distinct terranes that had been generated by two different processes: some kind of upper crustal recycling and stagnant lid tectonics. Meanwhile, that part of the Hadean Earth represented by the Barberton zircons may have been a long-lived regime of stagnant lid tectonics, replaced by dominant subduction at the end of the Eoarchaean. Yet the data suggest that into the Palaeoarchaean (3.6 to 3.2 Ga) and perhaps later, lid tectonics continued to operate somewhere, but at no time after 4.4 Ga was the Earth entirely subject to lid tectonics. Likewise, the authors insist that subduction was not of the plate-tectonic style, referring to some form of recycling of hydrated upper crustal mafic and ultramafic rocks into the mantle to undergo partial melting. Plate tectonics as we know it probably developed later in the Archaean. The early Earth had much higher heat flow than in later times, and thus the lithosphere was more ductile rather than brittle. The essence of modern tectonics is a series of rigid plates that extend down to the asthenosphere. When they deform it is largely through brittle failure of the entire lithosphere.