The Isle of Skye off the northwestern coast of Scotland is one of several areas in Britain that are world-class geological gems. Except for the Cuillin Hills that require advanced mountaineering skills it is easy to explore and has become a major destination for both beginners and expert geoscientists of all kinds. Together with the adjacent Isle of Raasay the area is covered by a superb, free geological guidebook (Bell, B. 2024. The Geology of the Isles of Skye and Raasay. Geological Society of Glasgow) together with 60 standalone excursion guides, and even an introduction to Gaelic place names and pronunciation. It is freely available from https://www.skyegeology.com/

Since 2018 Skye has also become a must-visit area for vertebrate palaeontologists. Beneath Palaeocene flood basalts is a sequence of Jurassic strata, both shallow marine and terrestrial. One formation, the Great Estuarine Group of Middle Jurassic (Bathonian, 174–164 Ma) age covers the time when meat-eating theropod- and herbivorous sauropod dinosaurs began to grow to colossal sizes from diminutive forebears. While other Jurassic sequences on Skye have notable marine faunas, its Bathonian strata have yielded a major surprise: some exposed bedding surfaces are liberally dotted with trackways of the two best known groups of dinosaur. The first to be discovered were at Rubha Nam Brathairean (Brothers’ Point) suggesting a rich diversity of species that had wandered across a wide coastal plain, also including the somewhat bizarre Stegosaurus. The latest finds are from a rocky beach at Prince Charles’s Point where the Young Pretender to the British throne, Charles Edward Stuart, landed and hid during his flight from the disastrous Battle of Culloden (16 April 1746). It was only in the last year or so that palaeontologists from the universities of Edinburgh and Liverpool, and the Staffin Museum came across yet more footprints (131 tracks) left there by numerous dinosaurs in the rippled sands of a Bathonian lagoon (Blakesley, T. et al. 2025. A new Middle Jurassic lagoon margin assemblage of theropod and sauropod dinosaur trackways from the Isle of Skye, Scotland. PLOS One, v. 20, article e0319862; DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0319862.

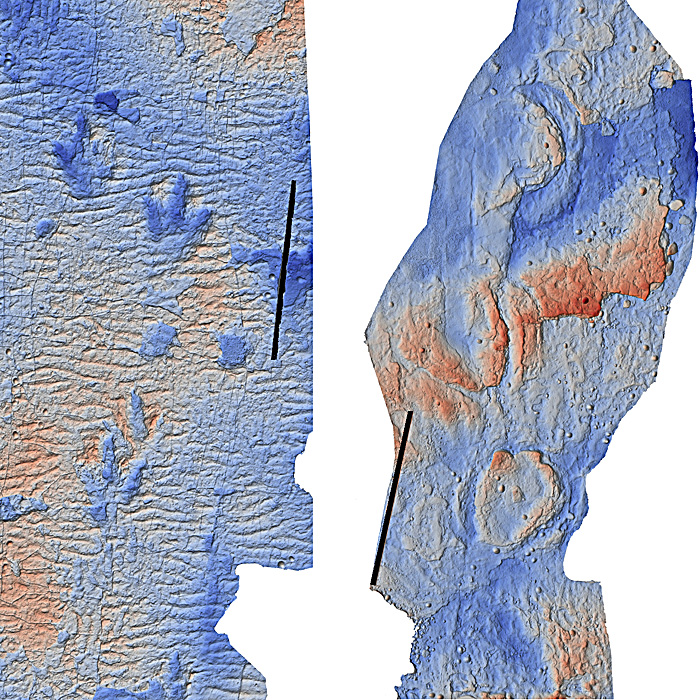

The Prince Charles’s Point site is partly covered by large basalt boulders, which perhaps account for the excellent preservation of the bedding surfaces from wave action. Two kinds of footprint are preserved (see image): those made by three-toed feet and by elephant-like feet that ‘squidged-up’ sediment surrounding than. Respectively these are suggested to represent the hind limbs of bipedal carnivorous theropods and quadrupedal herbivorous sauropods. They show that individual dinosaurs moved in multiple directions, but there is no evidence for gregarious behaviour, such as parallel trackways of several animals. They occur on two adjacent bedding surfaces so represent a very short period of time, perhaps a few days. The authors suggest that several individual animals were milling around, with more sauropods than theropods. What such behaviour represents is unclear. The water in an estuarine lagoon would likely have been fresh or brackish. They may have been drinking or perhaps there was some plants or carcases worth eating ? That might explain both kinds of dinosaurs’ milling around. The sizes of both sauropod and theropod prints average about 0.5 m. The stride lengths of the theropods suggest that they were between 5 to 7 metres long with a hip height of around 1.85 m. Their footprints resemble those reconstructed from skeletal remains of Middle Jurassic Megalosaurus, the first dinosaur to be named (by William Buckland in 1827). The sauropods had estimated hip heights of around 2 m so they may have been similar in size (around 16 m) to the Middle Jurassic Cetiosaurus, the first sauropod to be named (by Richard Owen in 1842).

A fully revised edition of Steve Drury’s book Stepping Stones: The Making of Our Home World can now be downloaded as a free eBook