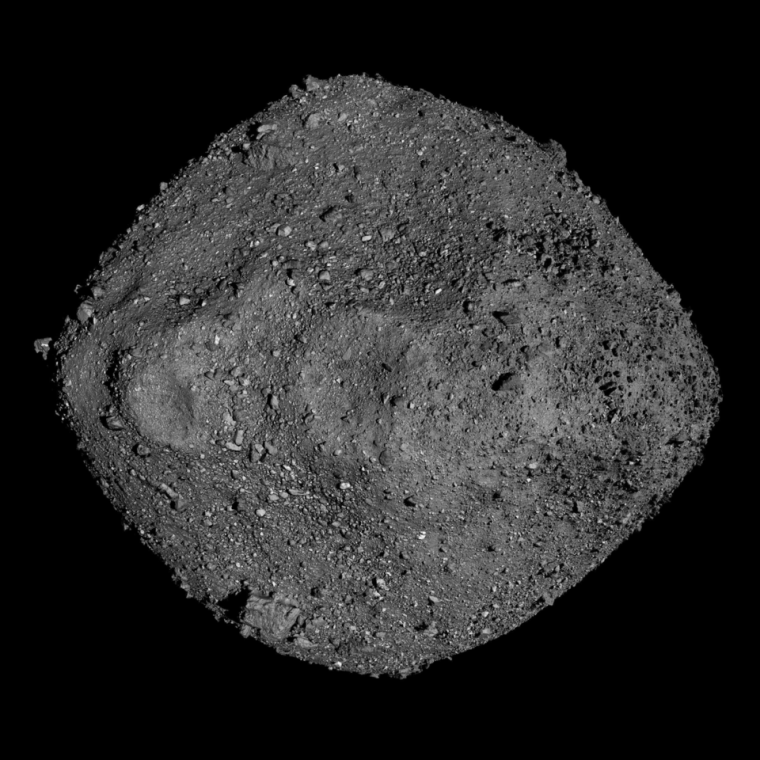

I must have been about ten years old when I last saw a ‘lucky dip’ or ‘bran tub’ at a Christmas fair. You paid two shillings (now £0.1) to rootle around in the bran for 30 seconds and grab the first sizeable wrapped object that came to hand:. In my case that would be a cheap toy or trinket, but you never knew your luck as regards the top prize. There is a small asteroid called 101955 Bennu, about half a kilometre across, whose orbit around the Sun crosses that of the Earth. So it’s a bit scary, being predicted to pass within 750,000 km of Earth in September 2060 and has a 1 in 1,880 chance of colliding with us between 2178 and 2290 CE. Because Earth-crossing asteroids are a cheaper target than those in the Asteroid Belt, in 2016 NASA launched a mission named OSIRIS-REx to intercept Bennu, image it in great detail, snaffle a sample and ultimately return the sample to Earth for analysis. This wasn’t a shot in the dark, as a lot of effort and funds were expended to target and then visit Bennu. But unlike me at the fair ground, NASA will be very happy with the outcome.

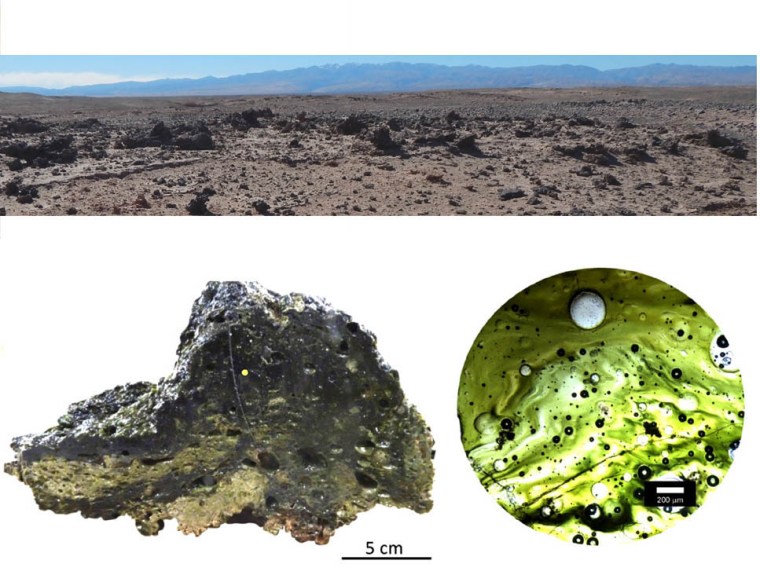

Bennu is a product of what might be regarded as ‘space sedimentation’, indeed a kind of conglomerate, being made up of boulders up to 58 m across set in gravelly and finer debris or ‘regolith’. High-resolution images revealed veins of carbonate minerals in the boulders. They suggest hydrothermal activity in a much larger parent body – one of many proto-planets accreted from interstellar gas and dust as the Solar System first began to form over 4.5 billion years ago. Its collision with another sizeable body knocked off debris to send a particulate cloud towards the Sun, subsequently to clump together as Bennu by mutual gravitational attraction. The carbonate veins can only have formed by circulation of water inside Benno’s parent.

The ‘REx’ in the mission’s name is an acronym for ‘Regolith Explorer’. Sampling was accomplished on 20 October 2020 by a soft landing that drove a sample into a capsule, and then OSIRIS-REx ‘pogo-sticked’ off with the booty. The capsule was dropped off by parachute after the mission’s return on 24 September 2023, in the manner of an Amazon delivery by drone to a happy customer. So, you can understand my ‘lucky dip’ metaphor. And NASA certainly was ‘lucky’ as the contents turned out to be astonishing, as related two years later by the analytical team in the US, led by NASA’s Angel Mojarro (Mojarro, A. et al. 2025.Prebiotic organic compounds in samples of asteroid Bennu indicate heterogeneous aqueous alteration. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science, v. 122, article e2512461122; DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2512461122).

The rock itself is made from bits of carbonaceous chondrite, the most primitive matter orbiting the Sun. It contains fifteen amino acids, including all five nucleobases that make up RNA and DNA – adenine (A), guanine (G), cytosine (C), thymine (T) and uracil (U) – as in AUGC and AGCT. Benno’s complement of amino acids included 14 of the 20 used by life on Earth to synthesise proteins. The fifteenth, tryptophan, has never confidently been seen in extraterrestrial material before. Alkylated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, also found in Bennu, are seen in abundance in interstellar gas clouds and comets by detecting their characteristic fluorescence when illuminated by mid-infrared radiation from hot stars using data from the Spitzer and James Webb Space Telescopes. These prebiotic organic compounds have been suggested to have played a role in the origin of life, but exposure to many produced by human activities are implicated in many cancers and cardiovascular issues. A second paper by Japanese biochemists and colleagues from the US was also published in early December 2025 (Furukawa, Y. and 13 others 2025. Bio-essential sugars in samples from asteroid Bennu. Nature Geoscience, v. 12, online article; DOI: 10.1038/s41561-025-01838). The authors identified several kinds of sugars in a sample from Bennu, including ribose – essential for building RNA – and glucose. Bennu also contains formaldehyde – a precursor of sugars – perhaps originally in the same brines in which the amino acids formed.

Yet another publication coinciding with the aforementioned two focuses on products of the oldest event in the formation of Bennu: its content of pre-solar grains (Nguyen, A.N. et al. 2025. Abundant supernova dust and heterogeneous aqueous alteration revealed by stardust in two lithologies of asteroid Bennu. Nature Astronomy, v. 9, p. 1812-1820; DOI: 10.1038/s41550-025-02688-3). In 1969 a 2 tonne carbonaceous chondrite fell near Allende in Mexico. The largest of this class ever found, it contained tiny, pale inclusions that eight years of research revealed to represent materials completely alien to the Solar System. They are characterised by proportions of isotopes of many elements that are very different from those in terrestrial materials. The anomalies could only have formed by decay of extremely short-lived isotopes that highly energetic cosmic rays produce in a manner analogous to neutron bombardment: they are products of nuclear transmutation. It is possible to estimate when the parent isotopes produced the anomalous ‘daughter’ products. One study found ages ranging from 4.6 to 7.5 Ga: up to three billion years before the Solar System began to form. It is likely that the grains are literally ‘star dust’ formed during supernovae in nearby parts of the Milky Way galaxy. Bennu samples contain six-times more presolar grains than any other chondritic meteorites. Nguyen et al. geochemically teased out grains with different nucleosynthetic origins. These ancient relics point to Bennu’s formation in a region of the presolar cloud that preceded the protoplanetary disk and was a mix of products from several stellar settings.

The results from asteroid Bennu support the key idea that that amino acid building blocks for all proteins and the nucleobases of the genetic code, together with other biologically vital compounds arose together in a primitive asteroid. Its evolution provided the physical conditions, especially the trapping of water, for the interaction of simpler components manufactured in interstellar clouds. Such ‘fertile’ planetesimals and debris from them almost certainly accreted to form planets and endowed them with the potential for life. What astonishes me is that Bennu contains the five nucleobases used in terrestrial genetics and 70% of the amino acids from which all known proteins are assembled by terrestrial life. But, as I try to explain in my book Stepping Stones: The Making of Our Home World, life as we know it arose, survived and evolved through a hugely complex concatenation of physical and chemical events lasting more than 4.5 billion years. The major events and the sequences in which they manifested themselves may indeed have been unique. Earth is a product of luck and so are we!

See also: Tabor, A. et al. 2025. Sugars, ‘Gum,’ Stardust Found in NASA’s Asteroid Bennu Samples. NASA article 2 December 2025. Glavin, D.P. and 61 others 2025. Abundant ammonia and nitrogen-rich soluble organic matter in samples from asteroid (101955) Bennu. Nature Astronomy, v. 9, p. 199-210; DOI: 10.1038/s41550-024-02472-9