The great megalithic structure is the centrepiece of a vast ritual landscape on a 780 km2 plateau known as Salisbury Plain, underpinned by Cretaceous limestone: the largest remaining area of calcareous grassland in northwest Europe. The earliest sign that the Plain was used for ritual purposes dates to ten thousand years ago (8,000 BCE), when Mesolithic hunter gatherers erected large wooden posts to define by an E-W line the Sun’s rise and setting at the equinoxes. The area seems to have been continuously populated until 4,000 BCE when the first Neolithic farmers settled the Plain and began building burial mounds (barrows) to celebrate notable individuals and families.

The Stonehenge monument began as a circular cemetery around 3,100 BCE. Its development to the astonishing structure that remains largely intact today occupied the Neolithic populace and succeeding Bronze Age immigrants for the next 1,600 years. This involved setting up and then repeatedly shuffling around several kinds of boulders or megaliths. The first, around 2,600 BCE, were 2 to 3 tonne blocks mainly of igneous rock (the ‘bluestones’), now known to have originated from outcrops of Ordovician volcanics in Pembrokeshire about 230 km to the west. Next to arrive was a 6 tonne grey-green sandstone slab, now lying flat (hence its being named the ‘Altar’ Stone) beneath a fallen, far bigger megalith,. Once thought to be of Welsh provenance – in the Brecon Beacons 150 km to the west – the Altar Stone is now beyond a shadow of doubt to have come from Devonian strata in northern Scotland, possibly Orkney. The final erection of 30 truly enormous ‘sarsens’ to create Stonehenge’s signature circle and inner ‘horseshoe’ of vertical slabs capped by lintels took place between 2,600 to2 400 BCE. Weighing up to 50 tonnes, the sarsens are locally derived from remnants of Lower Eocene (~55 Ma) sands cemented by chemically precipitated silica (SiO2) that once covered much of southern England.

After 1,600 BCE, serious fiddling with the various stones, the bluestones in particular, ceased. The monument may have remained in some form of use during the Iron Age: it could hardly have been ignored. The first record of antiquarian interest is from the late 17th century and continued sporadically until systematic excavation of archaeological features on the Plain got underway during the 19th century and continues to the present.

Much recent literature has concentrated on what Stonehenge was for and how it was built, leading to a rich eclecticism and a little experimentation. But given the size of its stones and the obviously exotic nature of some of them, there have been disputes between those who consider them to have been brought by natural means and those who suggest collective human endeavour. The latter would have involved vast amounts of labour, shifting the bluestones over 250 km, entire community muscle power to drag the locally occurring sarsens about 25 km from their probable source, and a journey of at least 700 km to get the Altar Stone in place. Since none of the stones could conceivably have been moved by river flow, the only natural alternative for their transport is by glacial action.

Such an ice-transport theory rests on at least one of the several known advances of Pleistocene ice sheets having reached as far south as Salisbury Plain and deposited upon it glacial till that contains material from NE Scotland and South Wales. The most obvious indicators of glacial transport are large erratic boulders strewn far from their source down a previous ice stream that their distribution helps to reconstruct. In Northern Britain a great many megaliths that people erected long ago are glacial erratics of one kind or another. Of course, glacial tills contain grains of all sizes ripped and ground from the course of glacial flow. No so obvious, but equally capable of revealing transportation paths. After ice sheets melt, the till that they dump is eroded so that exotic rock and mineral grains enter drainage systems, some to remain in stream sediments. Two geologists based at Curtin University in Perth, Western Australia collected river sands from four active drainage systems on Salisbury Plain to test the glacial-transport hypothesis for the Stonehenge megaliths (Clarke, A.J.I. & Kirkland, C.L. 2026. Detrital zircon–apatite fingerprinting challenges glacial transport of Stonehenge’s megaliths. Communications Earth & Environment, v. 7, article 54; DOI: 10.1038/s43247-025-03105-3).

Using standard mineral-separation techniques – removal of low-density minerals (mainly quartz and feldspar) and those that are magnetic – Anthony Clarke and Christopher Kirkland mounted and polished samples of the remaining high-density grains embedded in resin. Using automated X-ray spectroscopy they identified grains of two minerals, zircon and apatite, that can be dated using uranium and lead isotopes. Zircons are virtually absent from the underlying Chalk although phosphorus-rich horizons in that rock sometimes contain apatite, a complex calcium phosphate. Both minerals are commonly found in igneous and metamorphic rocks and, being chemically resistant and hard, are often present in sediments derived by erosion of such parent rocks. The authors analysed U-Pb isotopes using laser ablation plasma mass spectrometry of suitable grains of each mineral. The U-Pb data from 250 apatite grains revealed a dominant age peak at 60 Ma, roughly the base of the once overlying Palaeogene sediments. Far fewer grains hint at older ages (175, 215, 300 and 625 Ma) in the Mesozoic, Palaeozoic and Neoproterozoic. The 550 analysed zircons span an age range from the Silurian to Palaeoproterozoic (432 to 1870 Ma), with a few outliers as young as 285 Ma and as old as 3396 Ma.

These data seem to suggest that they can support virtually any glacial transport hypothesis, including that of the Altar Stone, let alone the Stonehenge bluestones. However, that would be to misunderstand the complexity of sediment transport in relation to their original provenance. Erosion from a bedrock source leads to transport and deposition in sedimentary rock. Later uplift and erosion of that secondary host rock is followed by later sediment transport to another rock repository and so on and so forth through the entire geological history of Britain, across its jumble of many tectonic terranes and the effects of numerous orogenic episodes! The Salisbury Plain chalk lands were covered by Palaeogene sedimentary rocks of the London Basin. And, lo and behold, one of those younger sediments, the Thanet Formation sandstones, tell much the same U-Pb story as do the modern river sediments of Salisbury! Those Palaeocene sands elsewhere directly overlie the Chalk and, in some localities on Salisbury Plain, still do today in the form of the chemically cemented sarsens. About 50 Ma ago (early Eocene) the Palaeocene rocks and those beneath were broadly buckled by the outermost ripples of the Alpine orogeny. Once eroded from above the Plain they would certainly have delivered that signature to the mercy of subsequent back and forth river transport. And indeed the sarsens, hard to miss in that landscape, perhaps still do so. Yet no one has thought to examine their content of heavy-mineral grains.

It does seem to me that the authors, perhaps inadvertently, walked into a sedimentological minefield in a vain attempt to put the lid on the fractious debate about human- versus glacial-transport of the Stonehenge megaliths. It is not their data that fling down a ‘challenge’ to the latter hypothesis (see their Conclusions), but the widely accepted absence of even the tiniest nugget of bluestone or Devonian sandstone on the vast and heavily excavated ritual landscape of Salisbury Plain, or indeed in the gravels of the streams that currently drain the Plain. But this where the plot thickens. A recent paper by one of the proponents of the glacial hypothesis (John, B.S. 2024. A bluestone boulder at Stonehenge: implications for the glacial transport theory. E&G Quaternary Science Journal v. 73, p. 117-134;DOI: 10.5194/egqsj-73-117-2024) describes a small piece of bluestone (22 × 15 × 10 cm) that was found during excavations at Stonehenge in 1924 and mysteriously ‘rescued’ by a Robert Newall and stored in his attic for almost 50 years, eventually examined by geologists and then returned to the attic. In 1976, two years before his death Newall passed it to the curator of Salisbury Museum ‘for safe keeping’. Brian John claims that its shape and surface texture suggests glacial transport. It also has several percussion scars suggesting that it had been worked, perhaps by someone hoping to make a stone tool. Unsurprisingly, Johns succeeded in provoking a storm of criticism from archaeologists largely of the human-transport wing of the controversy. And then there is the Mumbles Erratic, found at the eponymous Mumbles headland to the west of Swansea Bay. It too looks like a ‘bluestone’, but is it an erratic or from a Neolithic ship wreck carrying bluestones from Pembrokeshire?

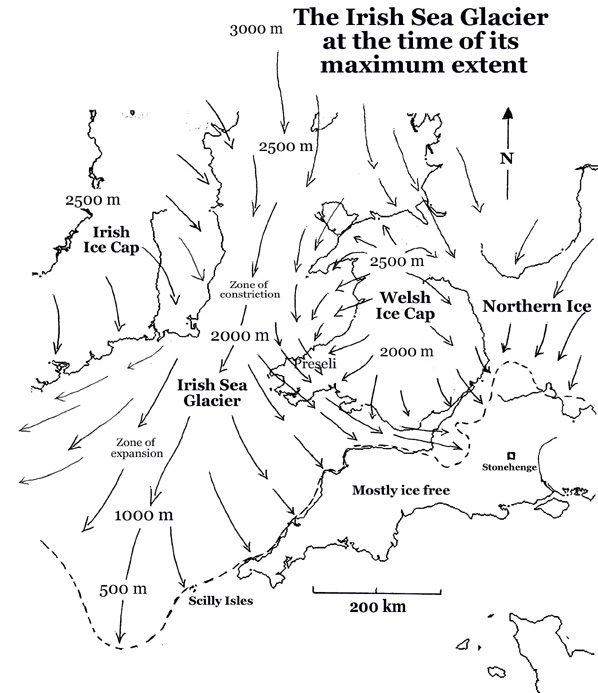

A great deal of work by British glaciologists has established the flow patterns and extent of major ice sheets, but only for four onshore, even though there is offshore evidence for repeated glaciation back as far as 2.5 Ma ago. The most extensive of these was the Anglian Stage between 478 and 424 ka ago. The figure above shows that the Irish Sea Glacier did not reach the Stonehenge area, but it did cross Pembrokeshire to reach Somerset on the eastern side of the Bristol Channel. Bluestone erratics may have been much more easily available than blocks hewn at their source in SW Wales, an hypothesis that is currently in vogue. Nope, the quest is not over …