For the last forty thousand years anatomically modern humans have been the only primates living on Planet Earth with a sophisticated culture; i.e. using tools, fire, language, art etcetera. Since Homo sapiens emerged some 300 ka ago, they joined at least two other groups of humans – Neanderthals and Denisovans – and not only shared Eurasia with them, but interbred as well. In fact no hominin group has been truly alone since Pliocene times, which began 5.3 Ma ago. Sometimes up to half a dozen species occupied the habitable areas of Africa. Yet we can never be sure whether or not they bumped into one another. Dates for fossils are generally imprecise; give or take a few thousand years. The evidence is merely that sedimentary strata of roughly the same age in various places have yielded fossils of several hominins, but that co-occupation has never been proved in a single stratum in the same place: until now.

The Koobi Fora area near modern Lake Turkana has been an important, go-to site, courtesy of the Leakey palaeoanthropology dynasty (Louis and Mary, their son and daughter-in-law Richard and Meave, and granddaughter Louise). They discovered five hominin species there dating from 4.2 to 1.4 Ma. So there was a chance that this rich area might prove that two of the species were close neighbours in both space and time. In 2021 Kenyan members of the Turkana Basin Institute based in Nairobi spotted a trackway of human footprints on a bedding surface of sediments that had been deposited about 1.5 Ma ago. Reminiscent of the famous, 2 million years older Laetoli trackway of Australopithecus afarensis in Tanzania, that at Koobi Fora is scientifically just as exciting for it shows footprints of two hominin species Homo erectus and Paranthropus boisei who had walked through wet mud a few centimetres below the surface of Lake Turkana’s ancient predecessor (Hatala, K.G. and 13 others, 2024. Footprint evidence for locomotive diversity and shared habitats among early Pleistocene hominins. Science, v. 386, p. 1004-1010; DOI: 10.1126/science.ado5275). The trackway is littered with the footprints of large birds and contains evidence of zebra.

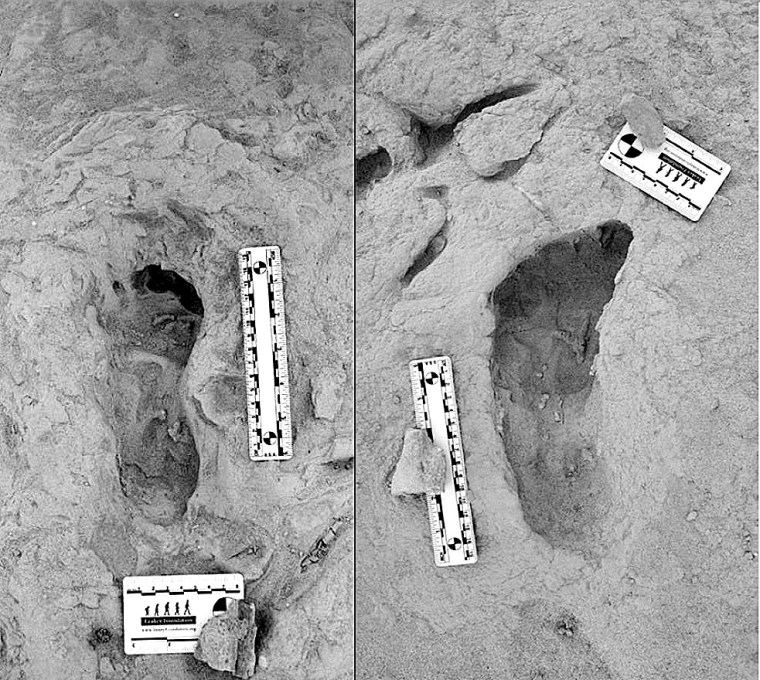

One set of prints attributed to H. erectus suggest the heels struck the surface first, then the feet rolled forwards before pushing off with the soles: little different from our own, unshod footprints in mud. They are attributed to H. erectus. The others also show a bipedal gait, but different locomotion. The feet that made them were significantly flatter than ours and had a big toe angled away from the smaller toes. They are so different that no close human relative could have made them. The local fossil record includes paranthropoids (Paranthropus boisei), whose fossil foot bones suggest an individual of that speciesmade those prints. It also turns out that a similar, dual walkers’ pattern was found 40 km away in lake sediments of roughly the same age. The two species cohabited the same terrain for a substantial period of time. As regards the Koobi Fora trackway, it seems the two hominins plodded through the mud only a few hours apart at most: they were neighbours.

From their respective anatomies they were very different. Homo erectus was, apart from having massive brow ridges, similar to us. Paranthropus boisei had huge jaws and facial muscles attached to a bony skull crest. So how did they get along? The first was probably omnivorous and actively hunted or scavenged meaty prey: a bifacial axe-wielding hunter-gatherer. Paranthropoids seem to have sought and eaten only vegetable victuals, and some sites preserve bone digging sticks. They were not in competition for foodstuffs and there was no reason for mutual intolerance. Yet they were physically so different that intimate social relations were pretty unlikely. Also their brain sizes were very different, that of P. Boisei’s being far smaller than that of H. erectus , which may not have encouraged intellectual discourse. Both persist in the fossil record for a million years or more. Modern humans, Neanderthals and Denisovans, as we know, sometimes got along swimmingly, possibly because they were cognitively very similar and not so different physically.

Since many hominin fossils are associated with riverine and lake-side environments, it is surprising that more trackways than those of Laetoli and Koobi Fora have been found. Perhaps that is because palaeoanthropologists are generally bent on finding bones and tools! Yet trackways show in a very graphic way how animals behave and interrelate with their environment, for example dinosaurs. Now anthropologists have learned how to spot footprint trace fossils that will change, and enrich the human story.

See also: Ashworth, J. Fossil footprints of different ancient humans found together for the first time. Natural History Museum News 28 November 2024; Marshall, M. Ancient footprints show how early human species lived side by side. New Scientist, 28 November 2024