A surprising number of animals pick up items from their surroundings and use them, mainly to get at otherwise inaccessible foodstuffs. What sets humans apart from such tool users is that we make them and for a long time part of our repertoire has been tools used to make other tools; so-called ‘machine tools’. An example is a piece of antler used to pressure-flake flint to give a stone blade a better edge, a more recent one is the increasing use of robots on assembly lines. Making a tool is impossible for a bird with only its beak and ill-adapted feet, while even a chimpanzee lacks various forms of grip needed for precisely directed force and manipulation. It was Frederick Engels who first focussed on the importance of the hand being freed to evolve the capacity for manual labour by the permanent adoption of an upright posture and gait, in his essay The Part Played by Labour in the Transition from Ape to Man written in 1876.

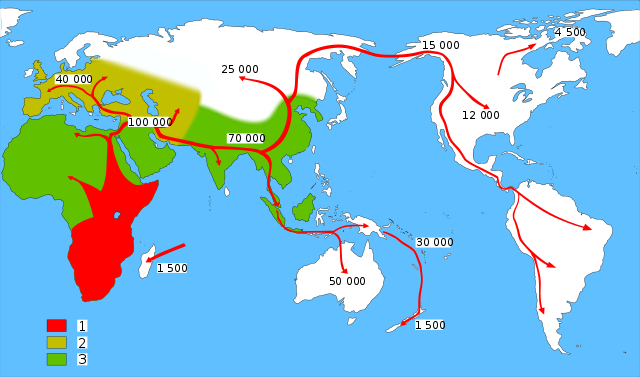

The earliest tools known turned up in 2.6 Ma old sediments at Gona in NE Ethiopia, while evidence for tool use is well accepted from cracked and sliced bones found in sediments dated at 2.5 Ma from Bouri in the same region. In neither case can the finds be tied to fossil remains of the makers and users, the earliest direct link emerging from famous Olduvai Gorge in western Tanzania, where crude Oldowan tools and worked bones occur with incomplete remains of a hominin, dubbed Homo habilis (‘handy man’) because of this association. Somewhat more controversial are bones that show cuts and scrape marks plus signs of having been cracked open that were found in a 3.4 Ma context at Dikika, also in Ethiopia, within the same sedimentary horizon as the young Australopithecus afarensis known as Selam (‘Hello’). The Dikika material is little different from 0.9 to 1.2 Ma younger bones at Bouri and Olduvai: the controversy seems to stem more from its much greater age and association with hominins deemed by some to have been incapable of creating tools.

An entirely novel approach to the issue of the first tools and their makers, which with little doubt would have tickled Engels no end, is a careful anatomical and physiological examination of fossil hominin hand bones in comparison with those of chimps and living humans (Skinner, M.M. et al. Human-like hand use in Australopithecus africanus. Science, v. 347, p. 395-399). The bones being scrutinized are the five metacarpals that form the links in the palms from muscles of the forearm to finger and thumb movements and thus to various kinds of grip. In humans there are a host of ways of gripping objects from the precision of opposed thumb and finger pinching, especially that using the forefinger, to the squeezing power grip that wraps thumb and all fingers around an object and makes a fist. The best a chimp can do is grabbing a branch, to which its knuckle-walking hands are well adapted. The tips of the metacarpals are mechanically loaded according to the types of grip used repeatedly in life and that works to modify the physical density of the tips’ spongy bone tissue in patterns that vary according to habitual usage of the hand and its digits. This new approach is reputedly far more diagnostic than the actual shape of metacarpal bones, and requires high-resolution CT scanning.

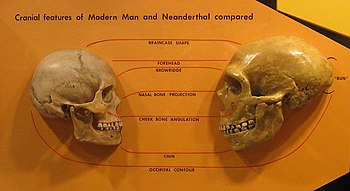

Known early human and Neanderthal tool-makers show very similar patterns: in fact they suggest far more heavy loading through various kinds of grip than the metacarpals of humans from the modern period. In 1.8 to 3.0 Ma old A. africanus and Paranthropus robustus (a gorilla-like but bipedal australopithecine) from South Africa metacarpals suggest that both were habitually using a tree-climbing grip, much as chimpanzees do, but more closely resembled modern human and Neanderthal committed tool users. Both were certainly capable of using forceful precision grips to make and use tools up to 0.5 Ma earlier than the date of the earliest known tools. So far the technique has not been applied to the palm bones of earlier hominins such as A. afarensis (2.9-3.9 Ma) and Orrorin tugenensis (~6 Ma). Despite the suggestion of tool-making capability, agreeing that it did take place in non-Homo hominins must await finds of tools, as well as signs of their use, in close association with fossil remains of their makers. The Dikika association is simply not enough. Yet, some bipedal being must have made tools before the date of the earliest ones (~2.6 Ma) discovered at Gona. Look at it this way: it is a lucky archaeologist who discovers every piece of evidence for a fundamental social change at one site. The fact that, by definition, the vast bulk of Pliocene and Pleistocene sediments that may contain the key evidence is either buried by younger material or was a victim of erosion, means that the chance of resolving the origin of the fundamental feature of human behaviour is tiny. The chance that scientists will continue looking is astronomically higher.