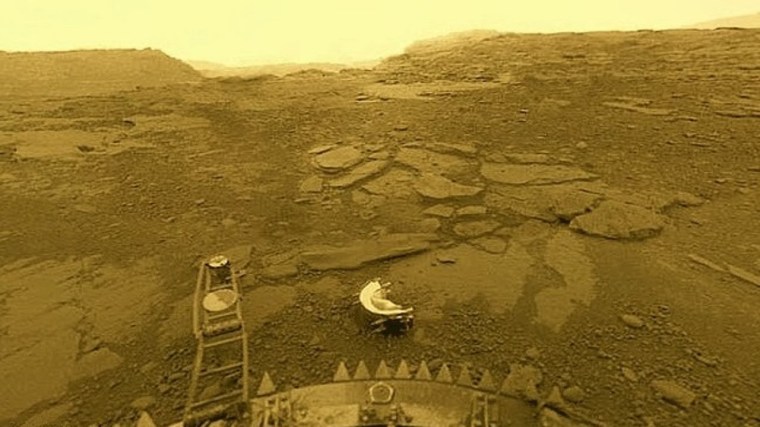

It is often said that Earth has a twin: Venus, the second planet from the Sun. That isn’t true, despite the fact that both have similar size and density. Venus, in fact, is even more inhospitable that either Mars or the Moon, having surface temperatures (~465°C) that are high enough to melt lead or, more graphically, those in a pizza oven. The only vehicles successfully to have landed on Venus (the Russian Venera series) survived for a mere 2 hours, but some did did send back data and images. That near incandescence is masked by the Venusian atmosphere that comprises 96.5% carbon dioxide, 3.5% nitrogen and 0.05 % sulfur dioxide, with mere traces of other gases including extremely low amounts of water vapour (0.002%) and virtually no oxygen. The dense atmosphere imposes a pressure at Venus’s surface tht is 92 times that on Earth: so dense that CO2 and N2 are, strictly speaking, not gases but supercritical fluids at the surface. At present Venus is definitely inimical to any known type of life. It is the victim of an extreme, runaway greenhouse effect.

As it stands, Venus’s geology is also very different from that of the Earth. Because its upper atmosphere contains clouds of highly reflective sulfuric acid aerosols only radar is capable of penetrating to the surface and returning to have been monitored by a couple of orbital vehicles: Magellan (NASA 1990 to 1994) and Venus Express (European Space Agency 2006 to 2014). The latter also carried means of mapping Venus’s surface gravitational field. The radar imagery shows that 80% of the Venusian surface comprises somewhat wrinkled plains that suggests a purely volcanic origin. Indeed more that 85,000 volcanoes have been mapped, 167 of which are over 100 km across. Much of the surface appears to have been broken into polygonal blocks or ‘campuses’ (campus is Latin for field) that give the impression of ‘crazy paving’. A peculiar kind of local-scale tectonics has operated there, but nothing like the plate tectonics on Earth in either shape or scale.

Many of the rocky bodies of the solar system are pocked by impact craters – the Earth has few, simply because erosion and sedimentary burial on the continents, and subduction of ocean floors have removed them from view. The Venusian surface has so few that it can, in its entirety, be surmised to have formed by magmatic ‘repaving’ since about 500 Ma ago at least. Earlier geological process can only be guessed at, or modelled in some way. A recent paper postulates that ‘there are several lines of evidence that suggest that Venus once did have a mobile lithosphere perhaps not dissimilar to Earth …’ (Weller, M.B. & Kiefer, W.S. 2025. The punctuated evolution of the Venusian atmosphere from a transition in mantle convective style and volcanic outgassing. Science Advances, v. 11, article eadn986; DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adn986). One large, but subtle feature may have formed by convergence similar to that of collision tectonics. There are also gravitational features that hint at active subduction at depth, although the surface no longer shows connected features such as trenches and island arcs. Local extension has been inferred from other data.

Weller and Kiefer suspect that Venus in the past may have shifted between a form of mobile plate tectonics and stagnant ‘lid’ tectonics, the vast volcanic plains having formed by processes akin to flood volcanism on a planetary scale. Venus’s similar density to that of Earth suggests that it is made of similar rocky material surrounding a metallic core. However, that planet has a far weaker magnetic field suggesting that the core is unable to convect and behave like a dynamo to generate a magnetic field. That may explain why the atmosphere of Venus is almost completely dry. With no magnetic field to deflect it the solar wind of charged particles directly impacts the upper atmosphere, in contrast to the Earth where only a very small proportion descends at the poles. Together with the action of UV solar radiation that splits water vapour into its constituent hydrogen and oxygen ions, the solar wind adds energy to them so that they escape to space. This atmospheric ‘erosion’ has steadily stripped the atmosphere of Venus – and thus its solid surface – of all but a minute trace of water, leaving behind higher mass molecules, particularly carbon dioxide, emitted by its volcanism. Of course, this process has vastly amplified the greenhouse effect that makes Venus so hot. Early on the planet may have had oceans and even primitive life, which on Earth extract CO2 by precipitating carbonates and by photosynthesis, respectively. But they no longer exist.

The high surface temperature on Venus has made its internal geothermal gradient very different from Earth’s; i.e. increasing from 465°C with depth, instead of from about 15°C on Earth. As a result, everywhere beneath the surface of Venus its mantle has been more able to melt and generate magma. Earlier in its history it may have behaved more like Earth, but eventually flipped to continual magmatic ‘repaving’. To investigate how this evolution may have occurred Weller and Kiefer created 3-D spherical models of geological activity, beginning with Earth-like tectonics – a reasonable starting point because of the probable Earth-like geochemistry of Venus. My simplified impression of what they found is that the periodic blurting of magma well-known from Earth history to have created flood-basalt events without disturbing plate tectonics proceeded on Venus with progressively greater violence. Such events here emitted massive amounts of CO2 into the atmosphere over short (~1 Ma) time scales and resulted in climate change, but Earth’s surface processes have always returned to ‘normal’. Flood-basalt episodes here have had a rough periodicity of around 35 Ma. Weller and Kiefer’s modelling seems to suggest that such events on Venus may have been larger. Repetition of such events, which emitted CO2 that surface processes could not erase before the next event, would progressively ramp up surface temperatures and the geothermal gradient. Eventually climatic heating would drive water from the surface into the atmosphere, to be lost forever through interaction with the solar wind. Without rainfall made acid by dissolved CO2, rock weathering that tempers the greenhouse effect on Earth would cease on Venus. The increased geothermal gradient would change any earlier rigid, Earth-like lithosphere to more ductile material, thereby shutting down the formation of plates, the essence of tectonics on Earth. It may have been something along those lines that made Venus inimical to life, and some may fear that anthropogenic global warming here might similarly doom the Earth to become an incandescent and sterile crucible orbiting the Sun. But as Mark Twain observed in 1897 after reading The New York Herald’s account that he was ill and possibly dying in London, ‘The report of my death was an exaggeration’. It would suit my narrative better had he said ‘… was premature’!

The Earth has a very large Moon because of a stupendous collision with a Mars-sized planet shortly after it accreted. That fundamentally reset Earth’s bulk geochemistry: a sort of Year Zero event. It endowed both bodies with magma oceans from which several tectonic scenarios developed on Earth from Eon to Eon. There is no evidence that Venus had such a catastrophic beginning. By at least 3.7 billion years ago Earth had a strong magnetic field. Protected by that thereafter from the solar wind, it has never lost its huge endowment of water; solid, liquid or gaseous. It seems that it did go through a stagnant lid style of tectonics early on, that transitioned to plate tectonics around the end of the Hadean Eon (~4.0 Ga), with a few hiccups during the Archaean Eon. And it did develop life as an integral part of the rock cycle. Venus, fascinating as it is, shows no sign of either, and that’s hardly surprising. Those factors and its being much closer to the Sun may have condemned it from the outset.

A fully revised edition of Steve Drury’s book Stepping Stones: The Making of Our Home World can now be downloaded as a free eBook