For decades, most of the news concerning our deep ancestry emerged from discoveries in sub-Saharan Africa at sites in Zambia, Tanzania, Kenya, South Africa, Ethiopia. The first week of 2026 decisively shifted that focus northwards to Chad and Morocco in two separate publications.

In 2002 ago the world of palaeoanthropology was in turmoil following the first discovery of fragments of what was then thought to be a hominid, or great-ape, cranium in Chad dated at around 7 Ma ago (Brunet, M. and 37 others 2002. A new hominid from the Upper Miocene of Chad, central Africa. Nature, v. 4418, p. 145-151;DOI:10.1038/nature00879). When pieced together the cranium looked like a cross between that of a chimpanzee and an australopithecine. Some suggested that the creature may have been a ‘missing link’ between the hominids and hominins; perhaps the ultimate ancestor of humans. Sahelanthropus tchadensis (nicknamedToumaï or ‘hope of life’ in the local Goran language) was undoubtedly enigmatic. The ‘molecular-clock’ age estimate for the branching of hominins from a common ancestor with chimpanzees was, in 2002, judged to be two million years later the dating of Sahelanthropus, so controversy was inevitable. Another point of contention was the size of Sahelanthropus’s canine teeth: too large for australopithecines and humans, but more appropriate for a gorilla or chimp. Moreover, Toumaï showed no indisputable evidence for having been bipedal. The Chadian site subsequently yielded three lower jaw bones and a collection of teeth, a partial femur (leg bone) and three fragmentary ulnae (forearm bones). The finds suggested that as many as five individuals had been fossilised. The femur gave an unresolved hint of an upright gait, yet the ulnas suggested Toumaï might equally have been arboreal; as could also be said for the australopithecines.

All the limb bones of Toumaïhave now been anatomically compared with those of hominins and apes (Williams S.A. et al. 2026. Earliest evidence of hominin bipedalism in Sahelanthropus tchadensis. Science Advances, v. 12, article eadv0130; DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adv0130). Scott Williams of New York University and co-workers from other US institutions show that although the leg bones are much the same size as those of chimpanzees, their proportions were more like those of hominins. They also showed features around the knees and hips needed for bipedalism and an insertion point for a tendon for the gluteus maximus muscle (buttock) vital for sustained upright locomotion, similar to the femurs of Orrorin tugenensis (see: Orrorin walked the walk; May 2008) and Ardipithecus ramidus. Unfortunately, an intact Sahelanthropus cranium showing a foramen magnum – where the skull attaches to the spine – continues to elude field workers. Its position distinguishes upright gait definitively.

See also: This ancient fossil could rewrite the story of human origins. Science Daily, January 3, 2026)

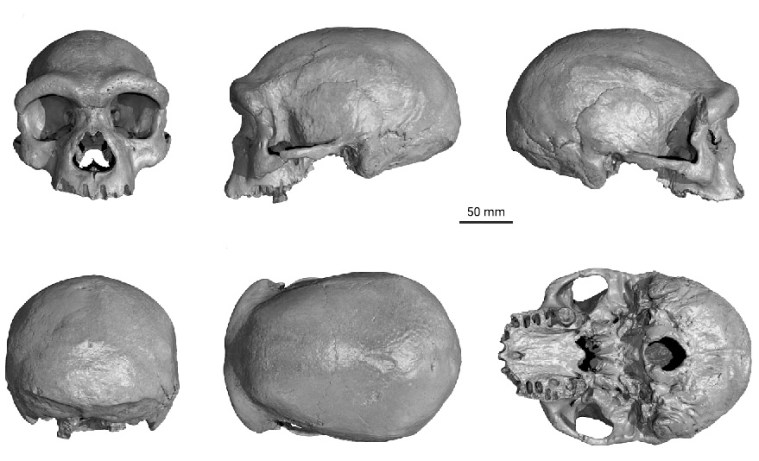

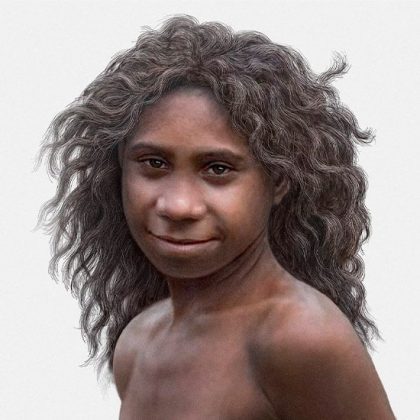

The second new advance concerns the joint ancestry of Neanderthals, Denisovans and anatomically modern humans (AMH), whose ancient genetics crudely suggest a last common ancestor living between 765 to 550 ka. This had previously been attributed to Homo antecessor found in the Gran Dolina cave at Atapuerca in northern Spain, roughly dated between 950 ka and 770 ka. (Incidentally, Gran Dolina has yielded plausible evidence of cannibalism). A novel possibility stems from hominin fossils excavated from a cave in raised-beach sediments near Casablanca in Morocco (Hublin, JJ. and 28 others, 2026 Early hominins from Morocco basal to the Homo sapiens lineage. Nature, v. 649 ; DOI: 10.1038/s41586-025-09914-y). The fossil-bearing sediments contain evidence for a shift in the Earth’s magnetic field (the Brunhes–Matuyama reversal) dated at 773 ka, much more precisely than the Atapuerca age span for H. antecessor. Jean-Jacques Hublin of CNRS in Paris and his multinational colleagues report that the fossils are similar in age to H. antecessor, yet are morphologically distinct, displaying a combination of primitive traits and of ‘derived features reminiscent of’ later Neanderthal, Denisovan and AMH fossils. The differences and shared features suggest that there may have been genetic exchanges between the Moroccan and Iberian population over a considerable period. The most obvious route would have been across the Straits of Gibraltar, but would have required some kind of water craft. An important question is ‘which population gave rise to the other?’

Larger and more robust hominin remains in Algeria dated at 1,000 ka – H. heidelbergensis? – resemble those found near Casablanca. They may have evolved to the latter. Similar possible progenitors to Iberian Homo antecessor have yet to be found in Western Europe. Homo erectus appeared in Georgia and Romania between 2.0 and 1.9 Ma, but the intervening million years or more have yielded no credible European forebears of H. antecessor. For the moment, incursion of a North African population into Europe followed by sustained contact is Hublin et al’s favoured hypothesis, rather than a European origin for Homo antecessor. For Neanderthals and Denisovans to have originated from such an African group, as has been suggested, requires finds of African fossils with plausible resemblance to what are predominantly Eurasian groups. The Iberian population migrated far and wide in Western Europe, as witnessed by stone tools and footprints dating to between 950 to 850 ka in eastern England. So it is equally possible that the Iberian group were progenitors of Neanderthals and Denisovans in Eurasia itself. At least for the moment, ancient genomes of the two H. antecessor groups are unlikely to be found in either Iberian or African fossils of the same antiquity. But, as usual, that will not stifle debate: a resort to the adage ‘absence of evidence is not evidence of absence’ seems appropriate to several research teams!

The oldest anatomically modern human fossils dated at ~300 ka, were also discovered in Morocco (see: Origin of anatomically modern humans, June 2017). Their isolation in the NW corner of the African continent poses a similar conundrum, as since then such beings went on to occupy wide areas of sub-Saharan Africa and then the world.