Earth has been through a great many catastrophes, but the vast majority of those of which we know were slow-burning in a geological sense. They resulted in unusually high numbers of extinctions at the species- to family levels over a few million years and the true mass extinctions seem to have been dominated by build ups of greenhouse gases emitted by large igneous provinces. Even the most famous at the end of the Cretaceous Period, which did for the dinosaurs and considerably more organisms that the media hasn’t puffed, was partly connected to the eruption of the Deccan flood basalts of western India. Yet the event that did the real damage was a catastrophe that appeared in a matter of seconds: the time taken for the asteroid that gouged the Chicxulub crater to pass through the atmosphere. Its energy was huge and because it was delivered in such a short time its sheer power was unimaginable. Gradually geologists have recognised signs of an increasing number of tangible structures produced by Earth’s colliding with extraterrestrial objects, which now stands at 190 that have been confirmed.

The frequency of impact craters falls off with age, most having formed in the last ~550 million years (Ma) during the Phanerozoic Eon, only 25 being known from the Precambrian, which spanned around 88 percent of geological time. That is largely a consequence of the dynamic processes of tectonics, erosion and sedimentation that may have obliterated or hidden a larger number. Earth is unique in that respect, the surfaces of other rocky bodies in the Solar System showing vastly more. The Moon is a fine example, especially as it has been Earth’s companion since it formed 4.5 billion years ago (Ga) after the proto-Earth collided with a now vanished planet about the size of Mars. The relative ages of lunar impact structures combined with radiometric ages of the surfaces that they hit has allowed the frequency of collisions to be assessed through time. Applied to the sizes of the craters such data can show how the amount of kinetic energy inflicted on the lunar surface has changed with time. During what geologists refer to as the Hadean Eon (before 4 Ga), the moon underwent continuous bombardment that reached a crescendo between 4.1 and about 3.8 Ga. Thereafter impacts tailed off. Always having been close to the Moon, the Earth cannot have escaped the flux of objects experienced by the lunar surface. Because of Earth’s much greater gravitation pull it was probably hit by more objects per unit area. Apart from some geochemical evidence from Archaean rocks (see: Tungsten and Archaean heavy bombardment; July 2002) and several beds of 3.3 Ga old sediment in South Africa that contain what may have been glassy spherules there are no signs of actual impact structures earlier than a small crater dated at around 2.4 Ga in NE Russia.

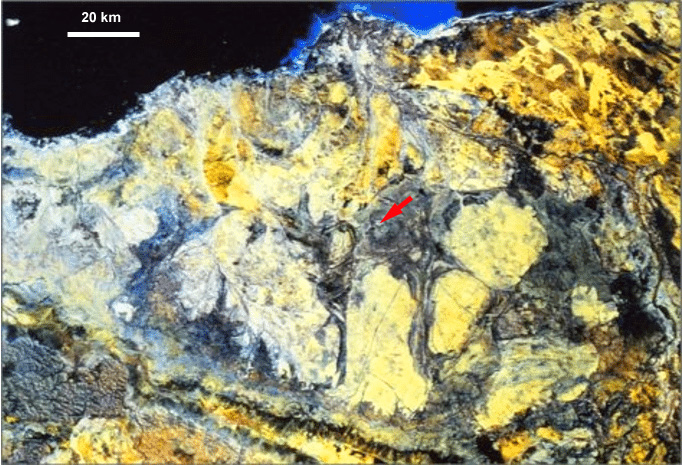

Now a group of geologists from Curtin University, Perth Western Australia, and the Geological Survey of Western Australia have published their findings of indisputable signs of an impact site in the northern part of Western Australia (Kirkland, C.L. et al. 2025. A Paleoarchaean impact crater in the Pilbara Craton, Western Australia. Nature Communications, v. 16, article 2224; DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-57558-3). In fact there is no discernible crater at the locality, but sedimentary strata show abundant evidence of a powerful impact in the form of impact-melt droplets in the form of spherules together with shatter cones. These structures form as a result of sudden increase in pressure to 2 to 30 GPa: an extreme that can only be generated in underground nuclear explosions, and thus likely to bear witness to large asteroid impacts. The shocked rocks are immediately overlain by pillow lavas dated at 3.47 Ga, making the impact the earliest known. It has been speculated that impacts during the Archaean and Hadean Eons helped create conditions for the complex organic chemistry that eventually to the first living cells. Considering that entry of hypervelocity asteroids into the early Earth’s atmosphere probably caused such compression that temperatures were raised by adiabatic heating to about ten times that of the Sun’s surface, their ‘entry flashes’ would have sterilised the surface below; the opposite of such notions. Impacts may, however, have delivered both water and simple, inorganic hydrocarbons. Together with pulverisation of rock to make ‘fertiliser’ elements (e.g. K and P) more easily dissolved, they may have had some influence. Their input of thermal energy seems to me to be of little consequence, for decay of unstable isotopes of U, Th and K in the mantle would have heated the planet quite nicely and continuously from Year Zero onwards.

A fully revised edition of Steve Drury’s book Stepping Stones: The Making of Our Home World can now be downloaded as a free eBook