Geochemists have gradually built a model of the proportions of the 92 naturally occurring elements that characterise the Solar System. It is based on systematic chemical analysis of meteorites, especially the ‘stony’ ones. One hypothesis for Earth formation is that the bulk of it chemically resembles a class of meteorites known as C1 carbonaceous chondrites. But there are important deviations between that and reality. For instance the relative proportions of the isotopes of several elements in meteorites have been found to differ. Because nuclei of all the elements and their individual isotopes have been shown to form in supernovae through nucleosynthesis, such instances are known as ‘nucleosynthetic anomalies’. An example is that of the isotopes of potassium (K), which was investigated by a team of geochemists from the Carnegie Institution for Science in Washington DC, USA and the Chengdu University of Technology, China led by Nicole Nie (Nie, N.X. et al. 2023. Meteorites have inherited nucleosynthetic anomalies of potassium-40 produced in supernovae. Science, v.379, p, 372-376; DOI: 10.1126/science.abn1783).

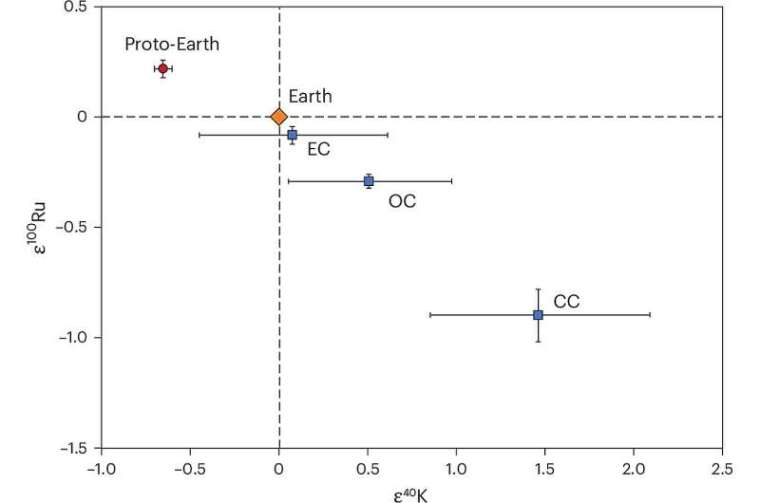

A measure for the magnitude of this nucleosynthetic anomaly is the ratio between the abundance in a sample of potassium’s rarest (40K) and its most common isotope (39K), divided by the ratio in an accepted standard of terrestrial rock. Since isotopically identical samples would yield a value of 1, the result has 1.0 subtracted from it to emphasise anomalies. Samples that are relatively depleted in 40K give negative values, whereas enriched samples give positive values. This measure is signified by ε40K, ε being the Greek letter epsilon. The authors found significant and variable positive anomalies of ε40K in carbonaceous chondrite (CC) meteorites, compared with non-carbonaceous (NC) meteorites. They also found that ε40K data in terrestrial rocks are quite different from those of CC meteorites. Indeed, they suggested that Earth was more likely to have formed from NC meteoritic material. Clearly, there seems to be something seriously amiss with the hypothesis that Earth largely accreted from C1 carbonaceous chondrites.

Three of the authors of Nie et al. and other researchers from MIT in Cambridge MA and Scripps Institution of Oceanography in San Diego CA, USA and ETH in Zurich, Switzerland have produced more extensive potassium isotope data to examine Earth’s possible discrepancy with the chondritic Earth hypothesis (Da Wang et al. 2025. Potassium-40 isotopic evidence for an extant pre-giant-impact component of Earth’s mantle. Nature Geoscience, v. 18, online article; DOI: 10.1038/s41561-025-01811-3). To better approximate the bulk Earth’s potassium isotopes they analysed a large number of terrestrial rock samples of all kinds and ages to compare with meteorites of different classes. Meteorites also have variable nucleosynthetic anomalies for ruthenium-100 (ε100Ru). So, ε40K and ε100Ru may be useful tracers with regards to Earth’s history. But, for some reason, the research group did not analyse ruthenium isotopes in the terrestrial samples.

Most samples of igneous rocks from different kinds of Phanerozoic volcanic provinces (continental flood basalts, island arcs, and ocean ridge basalts) showed no evidence of anomalous potassium isotopes. However, some young ocean-island basalts from Réunion and Hawaii showed considerable depletion in 40K. A quarter of early Archaean (>3.5 Ga) metamorphosed basaltic rocks from greenstone belts also showed clear 40K depletion. Yet no samples of granitic crust of similar antiquity showed any anomaly and nor did marine sediments derived from younger continental crust. Even the oldest known minerals – zircon grains from Jack Hills Western Australia – showed no anomalies. The authors suggest that both the anomalous groups of young and very ancient terrestrial basalts show signs that their parent magmas may have formed by partial mantle melting of substantial bodies of the relics of proto-Earth. To account for this anomalous mantle Da Wang et al. suggest from modelling that proto-Earths 40K deficit may have arisen from early accretion of meteorites with that property. Later addition of material more enriched with that isotope, perhaps as meteorites or through the impact with a smaller planet that triggered Moon-formation. That cataclysm was so huge that it left the Earth depleted in ‘volatile’ elements and in a semi-molten state. It reset Earth geochemistry as a result of several processes including the mixing induced by very large-scale melting. No radiometric dating has penetrated that far back in Earth history. However, in February 2004, Alex Halliday used evidence from several isotopic systems (Pb, Xe, Sr, W) to show that about two thirds of Earth’s final mass may have accreted in the first 11 to 40 Ma of its history.

Curiously, none of the hundreds of meteorites that have been geochemically analysed show the level of 40K depletion in the terrestrial samples. Nicole Nie has comments, “… our study shows that the current meteorite inventory is not complete, and there is much more to learn about where our planet came from.”

I’m persuaded to write this by ‘Piso Mojado’. And today – 23rd October – is the anniversary of the Creation of Earth, Life and the Universe in 4004 BCE, according to Archbishop James Ussher (1581-1656) by biblical reckoning, which always tickles me!

See also: Chu, J. 2025. Geologists discover the first evidence of 4.5-billion-year-old “proto Earth”. MIT News, 14 October 2025.