Championed as the earliest commonly found human species and, apart from anatomically modern humans (AMH), the most widespread through Africa and Eurasia. It also endured longer (~1.75 Ma) than any other hominin species, appearing first in East Africa around 2 Ma ago, the youngest widely accepted fossil – found in China – being around 250 ka old. The ‘erects’ arguably cooked their food and discovered the use of fire 1.7 to 2 Ma ago. The first fossils discovered in Java by Eugene Dubois are now known to be associated with the oldest-known art (430 to 540 ka) The biggest issue surrounding H. erectus has been its great diversity, succinctly indicated by a braincase capacity ranging from 550 to 1250 cm3: from slightly greater than the best endowed living apes to within the range of AMH. Even the shape of their skulls defies the constraints placed on those of other hominin species. For instance, some have sagittal crests to anchor powerful jaw muscles, whereas others do not. What they all have in common are jutting brow ridges and the absence of chins along with all more recently evolved human species, except for AMH.

This diversity is summed up in 9 subspecies having been attributed to H. erectus, the majority by Chinese palaeoanthropologists. Chinese fossils from over a dozen sites account for most of the anatomical variability, which perhaps even includes Denisovans, though their existence stems only through the DNA extracted from a few tiny bone fragments. So far none of the many ‘erect’ bones from China have been submitted to genetic analysis, so that connection remains to be tested. Several finds of diminutive humans from the Indonesian and Philippine archipelagos have been suggested to have evolved from H. erectus in isolation. All in all, the differences among the remains of H. erectus are greater than those used to separate later human species, i.e. archaic AMH, Neanderthals, Denisovans, H. antecessor etc. So it seems strange that H. erectus has not been split into several species instead of being lumped together, in the manner of the recently proposed Homo bodoensis. Another fossil cranium has turned up in central China’s Hubei province, to great excitement even though it has not yet been fully excavated (Lewis, D. 2022. Ancient skull uncovered in China could be million-year-old Homo erectus. Nature News 29 November 2022; DOI: 10.1038/d41586-022-04142-00; see also a video). Chances are that it too will be different from other examples. It also presents a good excuse to consider H. erectus.

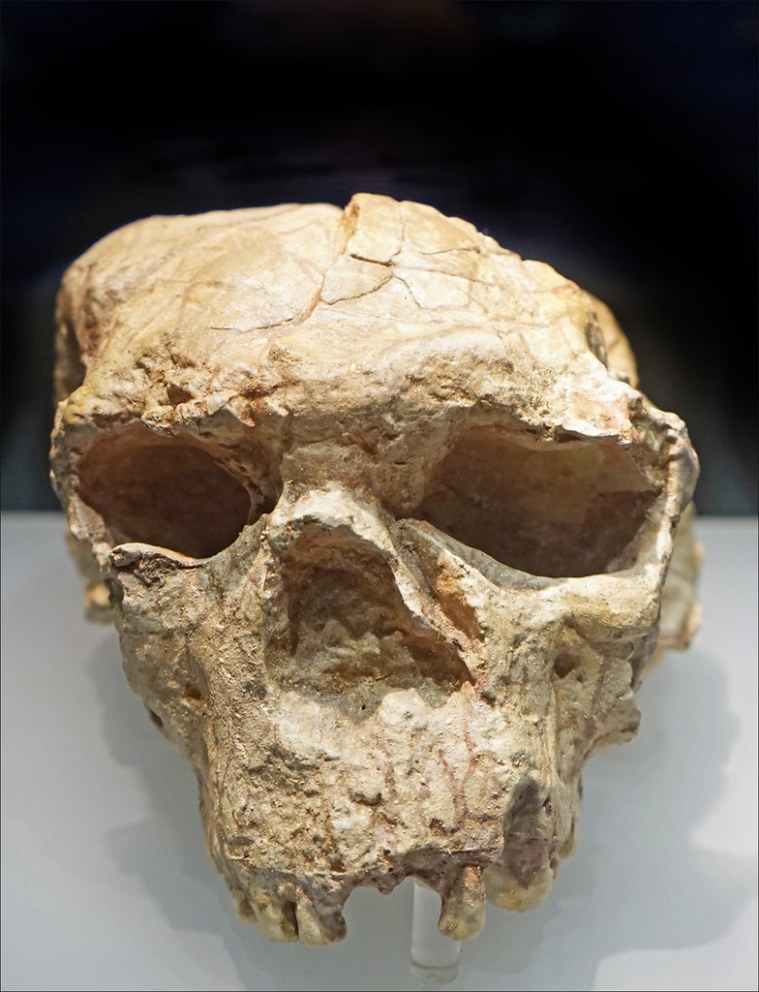

The complications began in Africa with H. ergaster, the originator of the bifacial or Acheulean multi-purpose stone tool at around 1.6 Ma (see: Flirting with hand axes; May 2009), the inventor of cooking and discoverer of the controlled use of fire. ‘Action Men’ were obviously smarter than any preceding hominin, possibly because of an increase of cooked protein and plant resources that are more easily digested than in the raw state and so more available for brain growth. The dispute over nomenclature arose from a close cranial similarity of H. ergaster to the H. erectus discovered in Java in the 19th century: H. erectus ergaster is now its widely accepted name. In 1991-5 the earliest recorded hominins outside Africa were found at Dmanisi, Georgia, in sediments dated at around 1.8 Ma (see: First out of Africa; November 2003) Among a large number of bones were five well-preserved skulls, with brain volumes less than 800 cm3 (see: An iconic early human skull; October 2013). These earliest known migrants from Africa were first thought to resemble the oldest humans (H.habilis) because of their short stature, but now are classified as H. erectus georgicus. They encapsulate the issue of anatomical variability among supposed H. erectus fossils, each being very different in appearance, one even showing ape-like features. Another had lost all teeth from the left side of the face, yet had survived long after their loss, presumably because others had cared for the individual.

The great variety of cranial forms of the Asian specimens of H. erectus may reflect a number of factors. The simplest is that continuous presence of a population there for as long as 1.5 Ma inevitably would have resulted in at least as much evolution as stemmed from the erects left behind in Africa, up to and including the emergence of AMH in North Africa about 300 ka ago. If contact with the African human population was lost after 1.8 Ma, the course of human evolution in Africa and Asia would clearly have been different. But that leaves out the possibility of several waves of migrants into Asia that carried novel physiological traits evolved in Africa to mix with those of earlier Asian populations. From about 1 Ma ago a succession of migrations from Africa populated Europe – H. antecessor, H. heidelbergensis, and Neanderthals and then AMH. So a similar succession of migrants could just as well have gone east instead of west on leaving Africa. Asia is so vast that migration may have led different groups to widely separated locations, partially cut-off by mountain ranges and deserts so that it became very difficult for them to maintain genetic contact. Geographic isolation of small groups could lead to accelerated evolution, similar to that which may have led to the tiny H. floresiensis and H. luzonensisdiscovered on Indonesian and Philippine islands.

Another aspect of the Asian continent is its unsurpassed range of altitude, latitude and climate zones. Its ecologically diversity offers a multitude of food resources, and both climate and elevation differences pose a range of potential stresses to which humans would have had to adapt. The major climate cycles of the Pleistocene would have driven migration across latitudes within the continent, thereby mixing groups with different physical tolerances and diets to which they had adapted. Equally, westward migration was possible using the Indo-Gangetic plains and the shore of the Arabian Sea: yet more opportunities for mixing between established Asians and newly arrived African emigrants.