The 1.5-2.0 km high Central Anatolian plateau in Türkiye has been rising since ~11 Ma ago: an uplift of about 1 km in the last 8 Ma. However, part of the southern Plateau shows signs of rapidly subsidence that has created the Konya Basin, marked by young lake sediments. Interferometric radar (InSAR) data from the European Space Agency’s Sentinel-1 satellite, which detects active movement of the Earth’s surface, reveal a crude, doughnut-shaped area of the surface that is subsiding at up to 50 mm per year. This ring of subsidence surrounds a core of active uplift that is about 50 km across (see the first figure). Expressed crudely, active subsidence suggests an excess of mass beneath the affected area, whereas uplift implies a mass deficit; in both cases within the lithosphere. So, when the InSAR data were published in 2020, it became clear that the lithosphere beneath Anatolia is doing something very strange.

Canadian and Turkish geophysicists set out to find a tectonic reason for such aberrant behaviour (Andersen, A.J. et al. 2024. Multistage lithospheric drips control active basin formation within an uplifting orogenic plateau. Nature Communications, v. 15, Article 7899; DOI: 10.1038/s41467-024-52126-7). They wondered if a process known as ‘drip tectonics’, first mooted as an explanation of anomalous features in some mountain belts in 2004 (see: Mantle dripping off mountain roots, October 2004; and A drop off the old block? May 2008) might be applicable to the Anatolian Plateau. The essence of this process is similar to the slab-pull force at the heart of subduction. Burial and cooling of basaltic material in oceanic lithosphere being driven beneath another tectonic plate converts its igneous mineralogy to the metamorphic rock eclogite, whose density exceeds that of mantle rocks. Gravity then acts to pull the changed material downwards. However, Anatolia shows little sign of subduction. But the mantle beneath shows seismic speed anomalies that hint at anomalously dense material.

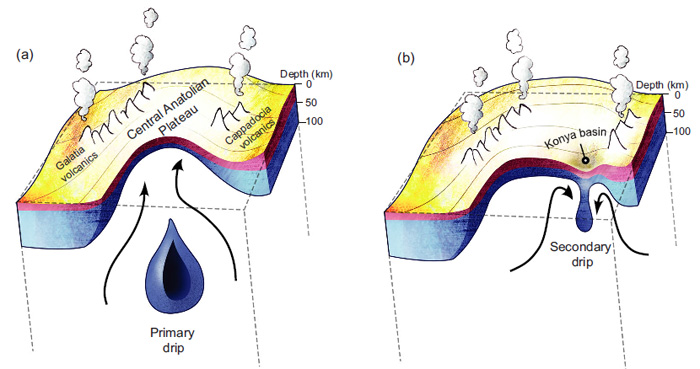

Seismic tomography shows that in a large volume 100 to 200 km beneath the central part of the Plateau S-waves travel faster than in the surrounding mantle. The higher speed suggests a body that is denser and more rigid than its surroundings. This could be a sinking, detached block of ‘eclogitised’ lithosphere whose disconnection from the remaining continental lithosphere has been causing the uplift of the Plateau that began in the Late Miocene. A smaller high-speed anomaly lies directly under the Konya Basin, but at a shallower depth (50 to 80 km) just beneath the lithosphere-asthenosphere boundary. The authors suggest that this is another piece of the lower lithosphere that is beginning to sink and become a ‘drip’. Still mechanically attached to the lithosphere the sinking dense block is dragging the surface down.

Andersen et al. instead of relying on computer modelling created a laboratory analogue. This consisted of a tank full of a fluid polymer whose viscosity is a thousand times that of maple syrup that represents the Earth’s deep mantle beneath. They mimicked an overlying plate by a layer of the same material with additional clay to render it more viscous – the model’s lithospheric mantle – with a ‘crust’ made of a sand of ceramic and silica spherules. A dense seed inserted into the model lithospheric mantle began to sink, dragging that material downwards in a ‘drip’. After that ‘drip’ had reached the bottom of the tank hours later, it became clear that another, smaller drip materialised along the track of the first and also began to sink. Monitoring of the surface of the ‘crust’ revealed that the initial drip did result in a basin. But the further down the drip fell the basin gradually became shallower: there was surface uplift. Once the initial drip had ‘bottomed-out’ the basin began to deepen again as the secondary drip formed and slowly moved downwards. The model seems to match the authors’ interpretation of the geophysics beneath the Anatolian Plateau. One drip created the potential for a lesser one, a bit like in inversion of the well-known slo-mo videos of a drop of milk falling into a glass of milk, when following the drop’s entry a smaller drop rebounds from the milky surface.

In Anatolia the last 10 Ma has not been just ups and downs of the surface corresponding to drip tectonics. That was accompanied by volcanism, which can be explained by upwelling of mantle material displaced by lithospheric drips. When mantle rises and the pressure drops partial melting can occur, provided the mantle material rises faster than it can lose heat: adiabatic melting.