One of the longest-lived hominin species that we know of was Paranthropus boisei, remains of which occur in East African sediments between 2.6 and 1.3 Ma. Others, including our own species, lasted nowhere near as long, except perhaps for Homo erectus who emerged around 1.9 Ma ago and is believed by some to have lingered on in Java until about 112 ka ago. However, when the unresolved muddle in the Middle Pleistocene of similar-looking hominin fossils is eventually unravelled – as now seems to be on the cards – that may limit the range of H. erectus to 1.9 -1.0 Ma. Paranthropoid remains are easily distinguished from those of their contemporary hominins – australopithecines and early species of Homo – being extremely robust compared with the ‘gracile’ members of the human line. They were also bipedal, but their fossil skulls are distinctive: massive teeth and jaws, and a bone crest on top of the cranium to which very powerful chewing muscles were attached. Once regarded as a sort of upright gorilla with vegetarian habits, evidence has accumulated since their first discovery that they may have been far more remarkable.

The earliest paranthropoid was P. aethiopicus from Ethiopia, dated at around 2.7 to 2.3 Ma, and believed to be the common ancestor of P. boisei and P. robustus found in Tanzania and South Africa respectively. Stone and bone tools associated with paranthropoid remains have been found in South and East Africa, some of which show signs of having been burnt. The connection between paranthropoids and both tool- and fire-making is clearly impossible to verify with certainty, and so too for their known association with australopithecine remains – or even the earliest known humans (Homo habilis) for that matter. Palaeoanthropologists are not likely to find a near-complete skeleton of any of these candidates with a tool grasped in the remains of a hand! The issue can be partly resolved if it can be shown that a fossil hand was capable of making and using tools. The fabled ‘opposable thumb’ that is capable of touching the tips of all four fingers is essential for the necessary ‘precision grip’. Isolated, 2 Ma-old thumb bones probably able to do that were found in the famous Swartkrans Cave in South Africa, but with no clue as to which hominin species had yielded them. In fact had that matter been resolved there and then, it would be not take the hominin story very far, simply because evidence for tool use – tools and cut marks on bone – goes back as far as 3.3 Ma, again with more than one candidate for the usefully endowed hominin species.

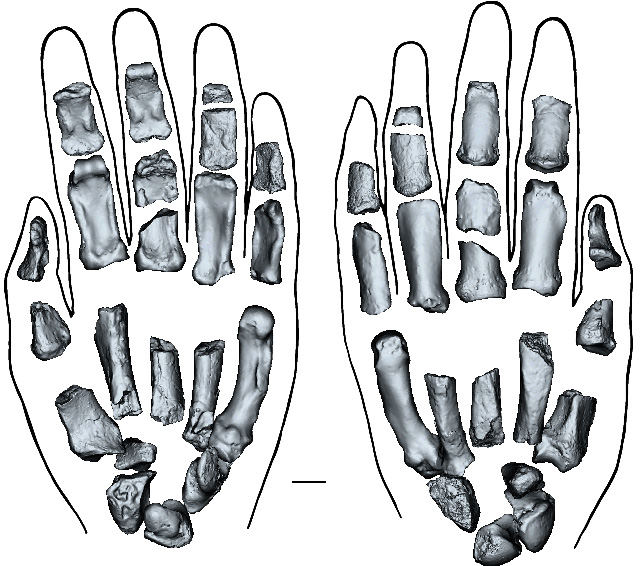

Remarkably, a group of scientists from the US, Canada, Australia, South Africa and Kenya have indeed unearthed from 1.5 Ma sediments on the shore of Lake Turkana in Kenya a near-complete left hand associated with cranial bones and teeth from Paranthropus boisei (Mongle,C.S. and 29 others 2025. New fossils reveal the hand of Paranthropus boisei. Nature v. 647, p. 944–951; DOI: 10.1038/s41586-025-09594-8). It is clear that the P. boisei hand shared some of the manipulative capacity of modern human hands, though it bears some resemblance to gorilla hands. That hand was probably nimble enough to make and use simple stone tools. It would also have had a powerful grip, sufficient for climbing and wielding a large stick. Yet again, it does not indicate which species first adopted tool making and use.

There are several interesting possibilities. It may be that a form of convergent evolution enabled two separate genera to become capable of such skills and the intellect to put them to use: tools, however simple, confer enormous evolutionary advantages. Had the antecedents of humans – presumably a species of Australopithecus – been the first, paranthropoids may have observed and adopted tools or vice versa. Just as possible, the – as yet unknown – common ancestor of both may have made this fundamental leap, which would have benefitted both vegetarian and omnivorous descendants. In that case the physiology of each group may have diverged with their lifestyles. Eating roots and leaves requires considerably more physical effort than getting sufficient protein and fats partly by devouring flesh.